Deaf gerbils 'hear again' after stem cell cure

- Published

Researchers hope they will be able to one day treat deafness with stem cells.

UK researchers say they have taken a huge step forward in treating deafness after stem cells were used to restore hearing in animals for the first time.

Hearing partially improved when nerves in the ear, which pass sounds into the brain, were rebuilt in gerbils - a UK study in the journal Nature reports., external

Getting the same improvement in people would be a shift from being unable to hear traffic to hearing a conversation.

However, treating humans is still a distant prospect.

If you want to listen to the radio or have a chat with a friend your ear has to convert sound waves in the air into electrical signals which the brain will understand.

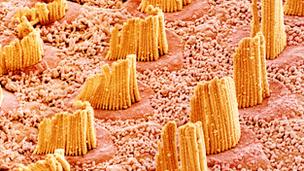

This happens deep inside the inner ear where vibrations move tiny hairs and this movement creates an electrical signal.

However, in about one in 10 people with profound hearing loss, nerve cells which should pick up the signal are damaged. It is like dropping the baton after the first leg of a relay race.

The aim of researchers at the University of Sheffield was to replace those baton-dropping nerve cells, called spiral ganglion neurons, with new ones.

They used stem cells from a human embryo, which are capable of becoming any other type of cell in the human body from nerve to skin, muscle to kidney.

A chemical soup was added to the stem cells that converted them into cells similar to the spiral ganglion neurons. These were then delicately injected into the inner ears of 18 deaf gerbils.

Over 10 weeks the gerbils' hearing improved. On average 45% of their hearing range was restored by the end of the study.

Dr Marcelo Rivolta said: "It would mean going from being so deaf that you wouldn't be able to hear a lorry or truck in the street to the point where you would be able to hear a conversation.

"It is not a complete cure, they will not be able to hear a whisper, but they would certainly be able to maintain a conversation in a room."

About a third of the gerbils responded really well to treatment with some regaining up to 90% of their hearing, while just under a third barely responded at all.

Gerbils were used as they are able to hear a similar range of sounds to people, unlike mice which hear higher-pitched sounds.

The researchers detected the improvement in hearing by measuring brainwaves. The gerbils were also tested for only 10 weeks. If this became a treatment in humans then the effect would need to be shown over a much longer term.

There are also questions around the safety and ethics of stem cell treatments which would need to be addressed.

'Tremendously encouraging'

Prof Dave Moore, the director of the Medical Research Council's Institute of Hearing Research in Nottingham, told the BBC: "It is a big moment, it really is a major development."

However, he cautioned that there will still be difficulties repeating the feat in people.

"The biggest issue is actually getting into the part of the inner ear where they'll do some good. It's extremely tiny and very difficult to get to and that will be a really formidable undertaking," he said.

Dr Ralph Holme, head of biomedical research for the charity Action on Hearing Loss, said: "The research is tremendously encouraging and gives us real hope that it will be possible to fix the actual cause of some types of hearing loss in the future.

"For the millions of people for whom hearing loss is eroding their quality of life, this can't come soon enough."

- Published20 June 2012

- Published16 November 2010

- Published20 April 2012

- Published16 February 2012

- Published20 March 2012