'My husband thought he had flu - but it was sepsis'

- Published

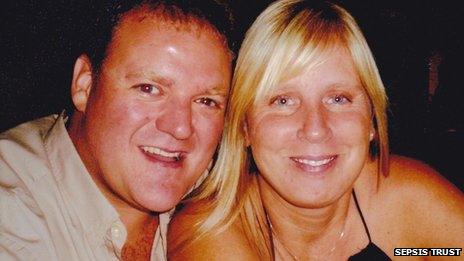

Jem was a fit, healthy man when he contracted sepsis

Karen Abbotts' husband Jem was recovering from a routine operation when he started to feel unwell.

He thought he had flu and went to bed to recover.

When he started vomiting and feeling feverish, Karen called their GP who prescribed antibiotics - but they were not strong enough to save him.

"Nothing had ever happened to our family," says his wife Karen. "Everyone was healthy. I just thought he was dehydrated."

When Jem was rushed to hospital a few days later after waking up delirious with uncontrollable diarrhoea, his family were worried but they expected doctors to say he would be back home riding his motorbike and playing with his children, Emily, 10, and Tom, eight, before too long.

Instead, when Karen followed behind the ambulance and reached A&E, she was told his heart had stopped and he was in a coma.

"It was an out-of-body experience. I thought 'this isn't happening to me'.

"I noticed a priest was in the room and I thought 'What is he doing here?' But he was there because Jem was dying."

Jem, 37, had contracted a bacterial infection which had entered his bloodstream and was causing his internal organs to fail.

The body can become overwhelmed and overreact to the infection, leading to a life-threatening condition known as sepsis. The immune system goes into overdrive, with potentially tragic consequences.

Karen recalls: "Sepsis was taking over his body, but the GP didn't realise and neither did we.

"He should have gone to hospital and got the right antibiotics straight away."

'Feel ghastly'

Sepsis claims over 37,000 lives in the UK every year, which is more than lung cancer, and more than breast cancer and bowel cancer combined.

Yet it is frequently mistaken for flu, or misdiagnosed by GPs.

Dr Ron Daniels, a consultant in intensive care in Birmingham and chief executive of the Global Sepsis Alliance, says there is little awareness of the disease.

"Patients can feel ghastly at home, not knowing what's wrong with them. Relatives don't know what to do either.

"GPs are unaware of what to look for and even in hospital doctors aren't aware of how to pick it up."

The task of identifying sepsis is made more difficult because there is no simple test. It has to be diagnosed by looking at symptoms.

The major signs to look out for are a very high (or very low) temperature, a racing heart beat, rapid breathing and confusion or slurring of speech.

If these are combined with the skin becoming pale or mottled, and the person has lost consciousness or not passed urine for more than 18 hours, they need urgent medical attention in a hospital.

Dr Daniels stresses the importance of responding quickly.

"It should be like heart attack care. There is a golden hour in which doctors must deliver the sepsis six, external."

These are a list of six simple tasks which have been shown to help save lives.

They include giving oxygen and antibiotics, and taking blood cultures.

Urgent help

Although people with acute illnesses and weak immune systems are more likely to get sepsis, it can affect fit, healthy people too - like Jem.

He spent eight days at home getting progressively more ill before he was finally given the medical help he needed. By then it was too late.

"They did everything they could but in the end the doctors said he was seriously brain damaged," said Karen.

"We hugged him and we turned his life support machine off."

She now wants everyone to know about the dangers of sepsis and the need to get it treated straight away, even if it they're not sure.

"Perhaps Jem couldn't have been saved, but others can be.

"It's awful that he has died but it helps me to know that I'm helping people. I want his death to be worthwhile."

Karen's children and extended family have helped her through some very difficult times in the past few years.

"The kids are both level-headed, they talk about their Dad all the time. And I see him in them both.

"Jem has come back to me through them."

- Published11 September 2012

- Published9 March 2012

- Published6 November 2010