'Three people, one baby' public consultation begins

- Published

- comments

A public consultation has been launched to discuss the ethics of using three people to create one baby.

The technique could be used to prevent debilitating and fatal "mitochondrial" diseases, which are passed down only from mother to child.

However, the resulting baby would contain genetic information from three people - two parents and a donor woman.

Ministers could change the law to make the technique legal after the results of the consultation are known.

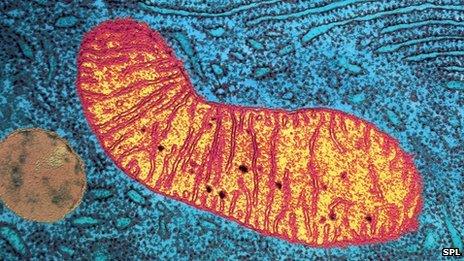

About one in 200 children are born with faulty mitochondria - the tiny power stations which provide energy to every cell in the body.

Most show little or no symptoms, but in the severest cases the cells of the body are starved of energy. It can lead to muscle weakness, blindness, heart failure and in some cases can be fatal.

Mitochondria are passed on from the mother's egg to the child - the father does not pass on mitochondria through his sperm. The idea to prevent this is to add a healthy woman's mitochondria into the mix.

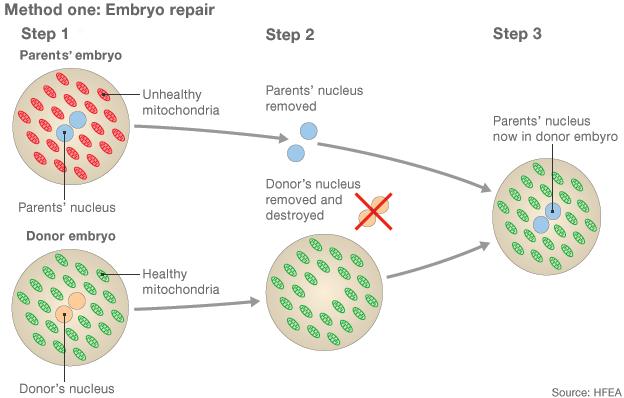

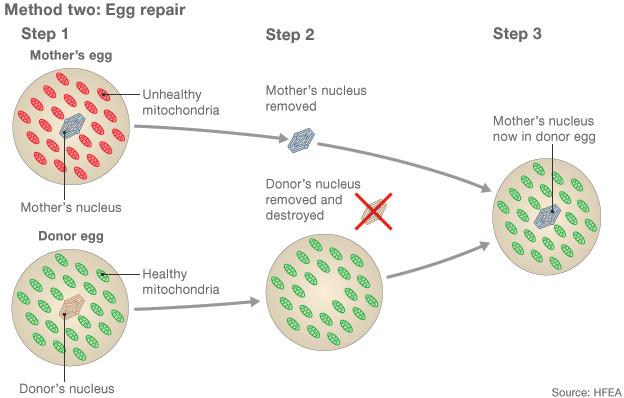

Two main techniques have been shown to work in the laboratory, by using a donor embryo or a donor egg.

How do you make a baby from three people?

1) Two embryos are fertilised with sperm creating an embryo from the intended parents and another from the donors. 2) The pronuclei, which contain genetic information, are removed from both embryos but only the parents' is kept 3) A healthy embryo is created by adding the parents' pronuclei to the donor embryo, which is finally implanted into the womb

Step 1. Eggs from a mother with damaged mitochondria and a donor with healthy mitochondria are collected. Step 2. The majority of the genetic material is removed from both eggs. Step 3. The mother's genetic material is inserted into the donor egg, which can be fertilised by sperm.

However, mitochondria contain their own genes in their own set of DNA. It means any babies produced would contain genetic material from three people. The vast majority would come from the mother and father, but also mitochondrial DNA from the donor woman.

This would be a permanent form of genetic modification, which would be passed down through the generations.

It is one of the ethical considerations which will be discussed as part of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority's consultation, external.

The chair of the organisation, Prof Lisa Jardine, said: "It is genetic modification of the egg - that is uncharted territory. Once we have genetic modification we have to be sure we are damn happy."

She said it was a question of "balancing the desire to help families have healthy children with the possible impact on the children themselves and wider society".

Other ethical issues will also be considered, such as how children born through these techniques feel, when they should be told, the effect on the parents and the status of the donor woman - should she be considered in the same way as an egg donor in IVF?

Hundreds of mitochondria in every cell provide energy

It is not the first time these issues have been discussed. A report by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, external said the treatment was ethically OK, but the group Human Genetics Alert said the procedure was unnecessary, dangerous and set a precedent for genetically modified designer babies.

The consultation will run until 7 December and the conclusions will be presented to ministers next spring.

Research into the area is legal in the UK, but it cannot be used in patients.

Prof Lisa Jardine: We need public opinion on 3-person IVF

However, treatments in IVF clinics will be years away even if the public and ministers decide the techniques should go ahead. There are still questions around safety which need to be addressed.

One of the pioneers of the methods, Prof Mary Herbert from Newcastle University, said: "We are now undertaking experiments to test the safety and efficacy of the new techniques.

"This work may take three to five years to complete."

- Published17 September 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published11 March 2011

- Published19 January 2012