Museum of London showcases 'bodysnatchers'

- Published

Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men is a new exhibition at the Museum of London drawing together artefacts that show the relationship between surgeons' anatomical study and the men who supplied them with the corpses.

The Anatomy Act 1832 gave surgeons and students of anatomy the freedom to dissect donated bodies. Before this, only the bodies of executed murderers could be used.

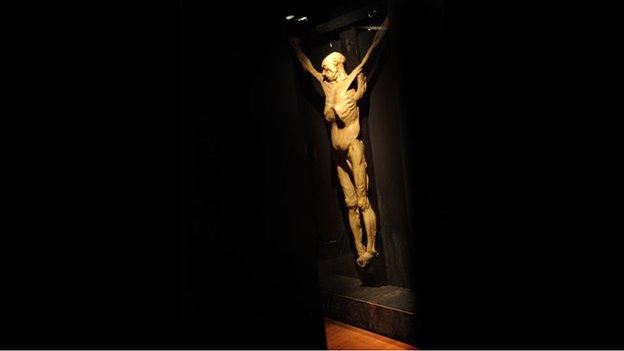

In 1801, sculptor Thomas Banks and artists Benjamin West and Richard Crossway set out to show that most depictions of the Crucifixion were anatomically incorrect - acquiring a body straight from the gallows, nailing it into position before being flayed and cast in plaster by Banks.

In 2006, the Museum of London Archaeology excavated a burial ground at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. The excavation revealed some 262 burials, containing a mix of bones with evidence of dissection, autopsy, amputation, and bones wired for teaching.

Medical pioneers went to great length to increase anatomical understanding and the dwindling number of executions meant the demand for corpses outstripped the supply.

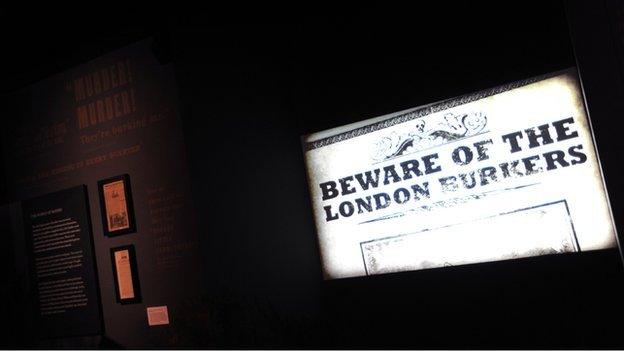

Gangs of body snatchers, also known as resurrection men, stole cadavers from the capital’s cemeteries to sell to the surgeon anatomists.

Many people were fearful of being exhumed and so heavily riveted iron coffins became a popular choice for a secure grave. This one was found in the crypt at St Bride’s church in Fleet Street. It bears the name Mrs Campbell, who died in 1819, aged 63 years.

Surgeons were developing new methods for the study and teaching of anatomy. The excavation evidence suggests that for a period of the 19th Century the London hospital had bypassed the body snatchers and used their unclaimed deceased patients for dissection practice.

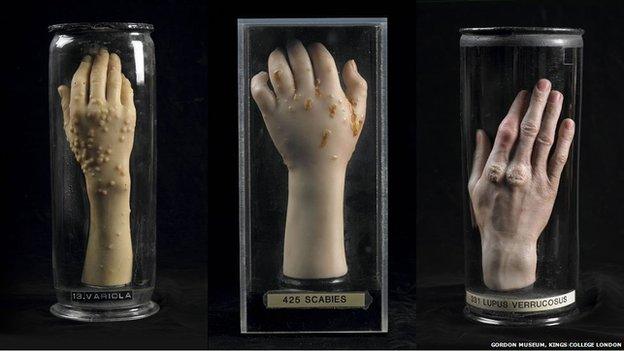

Classes with direct contact with contagious diseases were not feasible so models were used instead. Joseph Towne made hundreds of wax examples, cast from living patients, in order to aid the students' study.

Many surgeons in early 19th Century London faced a stark choice: should they hone their skills on stolen corpses or practise on their living patients?

The gruesome quest for bodies to dissect is explored in a major new exhibition at the Museum of London.

The display highlights the gruesome trade of "resurrection men", plundering graveyards to meet demand from the city's anatomy and medical schools.

Surgery in the early 1800s was a brutal business. The standard treatment for a broken bone was amputation. There was no anaesthetic or antiseptic. There was a risk of death from blood loss or infection, even after successful operations.

These procedures demanded speed and precision, but that in turn demanded practice. In the early 1800s the only legal source of bodies for dissection was executed criminals, transported straight from the gallows.

Yet by 1820 London had four major hospitals offering dissection classes and 17 private anatomy schools. For many, obtaining bodies for dissection was a problem.

All too often the solution was provided by gangs of grave robbers, raiding cemeteries and offering corpses for cash. Some even resorted to murder. These were the "resurrection men".

Their activities provoked widespread fear and hatred. The poorest in society were the most vulnerable. Many dreaded the stigma of dissection - a fate associated with convicted murderers - and there was a widespread belief that salvation was possible on the day of judgement only if the body was whole.

These themes are explored in vivid detail in a new exhibition at the Museum of London called Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men.

It was inspired by the discovery in 2006 of skeletal remains in a forgotten burial ground at the Royal London Hospital, that was in use between 1825 and 1841. The excavation revealed more than 260 burials.

Some contained just one person but many had a mix of bones, with evidence of dissection, autopsy and bones wired together for teaching. There were also dissected bodies of animals, used for comparative purposes.

'Sombre reminder'

Jelena Bekvalac, a curator at the museum and expert in this field, says this was an extraordinary find.

"By drawing together the extraordinary archaeological discoveries from 2006 and specialist research about London's body-snatching trade in the early 19th Century, we have been able to shine a light on a fascinating and critical period in the capital's history.

"For the first time we will display the human remains from the excavation and reveal their story - lost for so long and yet so important - providing a poignant and sombre reminder of a real truth that with medical advancement there is rarely no human cost."

The exhibition also includes surgical tools from the period, including a skull saw and full amputation set. There are painstakingly detailed wax depictions of internal anatomy by the 19th Century modeller Joseph Towne, who worked at Guy's Hospital for more than 50 years.

Revulsion over the infamous Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh, and the gruesome activities of bodysnatchers in London, led to the 1832 Anatomy Act. The exhibition examines the arguments this provoked at the time for and against the controversial legislation which heralded the demise of the resurrection men.

The act ruled that any bodies left unclaimed could be given up for dissection. It is estimated that over the next 100 years, 57,000 corpses were supplied - the great majority from workhouses, asylums and hospitals.

The exhibition looks at the "legacy of fear" bequeathed by the act - that falling into poverty could mean the state claiming your body after death.

Professor Vishy Mahadevan, from the Royal College of Surgeons, says the impact of the resurrection men was not entirely negative.

"They were just doing it for the money. The fresher the body, the more they got. But the indirect consequence of that was lasting good, in terms of the wonderful descriptions of anatomy that were given by great and industrious surgeons of that time, such as Sir Astley Cooper."

Sharon Ament, the museum's director, says the exhibition gives a fascinating insight into London's history.

"The legacy of this time is to be found in every anatomical reference book and surgical training course today.

"The story is told through fascinating displays mixing never-before-seen human remains with exquisite illustrations, objects and multimedia interpretation."

Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men runs from 19 October 2012 to 14 April 2013 at the Museum of London.

- Published17 January 2012