Battling the bacterial threat to modern medicine

- Published

Susan Watts / Antibiotics

The arrival of antibiotics in the 1940s revolutionised healthcare, but bacteria are fighting back and doctors and scientists are warning that ever-evolving resistant strains are putting modern medicine at risk.

"Antibiotics are losing their effectiveness at a rate that is both alarming and irreversible," said the Chief Medical Officer for England and Wales, Dame Sally Davies, earlier this month.

Microbiologist at the University of Birmingham, Prof Laura Piddock, told BBC's Newsnight that antibiotics are miracle drugs which underpin all areas of 21st Century medicine.

"But if we allow resistance to proliferate, then we undermine all of those medical advances," she said.

Unusually, Prof Piddock, and other specialists like her, are campaigning to persuade governments and industry to do more to preserve current antibiotics, and find new ones.

They are concerned that we overuse these drugs, most recently through online sales on the internet.

Prof Piddock explained that when you take an antibiotic you are having an impact not only on your health, but potentially on that of other people too.

"It's not like other types of medicine," she explained.

"For instance if I have a headache, I take a tablet for my headache, but if I take an antibiotic, all of the bacteria in my body are exposed to that antibiotic and I could be selecting drug-resistant strains, and I could be sharing them," she said.

Her point is that we are taking a risk for others as well as ourselves.

Ironically, in some cases, we may not even have needed the antibiotic in the first place. If we have a viral infection, for example, it will not respond to antibiotics.

The Department of Health has guidelines warning people about the safety risks of buying any drug online.

And there are guidelines for both doctors and pharmacists about online prescribing in general, from both the General Medical Council and the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPC).

The GPC told Newsnight that it is developing guidance on internet pharmacy "for the owners and superintendent pharmacists of internet pharmacies, and will consult on this guidance next year."

But there appears to be no specific move to limit sales of antibiotics online, in light of broader concerns about preserving antibiotic effectiveness.

Rather, the focus at the moment seems to be on protecting the safety of individual patients.

Biological pump

Bacteria become resistant in a process that Prof Piddock describes as a form of evolution, where the fittest bacteria survive - that is, the ones that can withstand antibiotics.

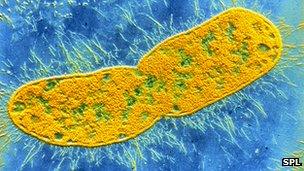

Klebsiella pneumoniae's double cell wall means it is resistant to many antibiotics

The more we use antibiotics, the more we unwittingly encourage those resistant bacteria to thrive.

There are two main groups of bacteria - called gram-positive and gram-negative - and it is this second group that is causing growing concern amongst microbiologists.

Gram-negative bacteria have a double cell wall - with a sort of biological pump in-between.

"Gram-negative bacteria have two barriers, which gram-positive bacteria don't have," said Prof Piddock.

"It's very clever… they have a three-part system that works like a vacuum cleaner. Any drug that gets in they are immediately able to pump straight out," she added.

This built-in pump makes it harder to design antibiotics that will destroy them.

Klebsiella, a bacteria that is often seen in urinary and lung infections, is a case in point.

In recent years it has developed resistance to our most effective antibiotics, and we have had to turn to our reserves, a class of antibiotic called carbapenems.

At the moment, around 2% of Klebsiella infections in the UK are resistant to carbapenem antibiotics.

Most antibiotics only treat gram-positive bacteria

But resistance has shot up in the US and in parts of Europe.

Director of antibiotic research monitoring at the Health Protection Agency, Prof David Livermore, explained that southern Europe was a good example of what can happen.

"As early as 2008 there were problems in Greece, with 40% of Klebsiella resistant to carbapenems," he said.

"In Italy, in 2008, it was between 1% and 5% resistance, that's no worse than our present problems. But by 2010 resistance was up at 17%. And according to the most recent data, resistance in Klebsiella in Italy is now up at 30%," he added.

Prof Livermore said it was vital that the UK avoids following Italy's trajectory, as losing the use of carbapenems against bacteria like Klebsiella would leave us with "rather poor, rather toxic, not very good antibiotics - we're down to the bottom of the barrel."

'Untreatable infections'

Prof Piddock said people tend to think that because there are over 200 antibiotics available, we are fine.

But she said the vast majority are for gram-positive bacteria. Worse, many drug companies have moved away from antibiotic development in recent years.

She warned that we must stop resistant strains reaching patients in the first place to avoid the unthinkable.

"For those patients who get an infection by a gram-negative bacterium, we'll see untreatable infections," said Prof Piddock,

"In some wards in the UK this has already happened.

"If we don't sort out the problem of antibiotic resistance then these wonderful medical advances that we take for granted now - 21st Century medicine - hip replacements, cancer chemotherapy - they're not going to be possible, because patients are succumbing to infections that were previously treatable."

Bacteria breed quickly, and in ways that can surprise the experts.

No-one can say for sure what the next big resistant threat will be, only that there will be more.

Prof Livermore uses the analogy of coast erosion.

"One year you're comfortable, your house is a mile from the cliff edge," he said.

"But come back in 10 years' time, and it is 100 yards (90m) away, and very hard to get insurance. That's where we are with antibiotic resistance," he added.

Watch Susan Watts' full report on Newsnight on Friday, 30 November 2012 at 22:30 GMT. Or watch afterwards on BBC iPlayer.

- Published14 November 2012

- Published16 November 2012

- Published11 October 2012

- Published7 April 2011