Born too soon - what is the outlook for severely premature babies?

- Published

- comments

Kai was born at 24 weeks

Fragile, tiny and battling for life. That is the fate of Kai and other babies born too soon. I met him with his parents Becky and Robert at Homerton hospital in east London.

"When I found out Becky had gone into labour I thought that's impossible" Robert told me. "It's still shocking to see how small he is but Kai is putting on weight and seems to be getting stronger every day."

Kai was born at 25 weeks and five days gestation and weighed 690g (one and a half pounds). He has put on 80g (three ounces) in the two weeks since his birth so was born even smaller than in the image above.

New research, external published in the British Medical Journal shows that there have been improvements in the survival rate of severely premature babies. My colleague James Gallagher has written about the research here.

But the toll on families, the NHS and the children themselves is immense with the outcomes worsening the earlier the baby is born. In 2006, of 442 live births at 24 weeks, 178 survived. Of 339 live births at 23 weeks, just 66 survived.

Doctors have to decide - in consultation with the parents - whether to intervene and offer life support to such seriously ill babies.

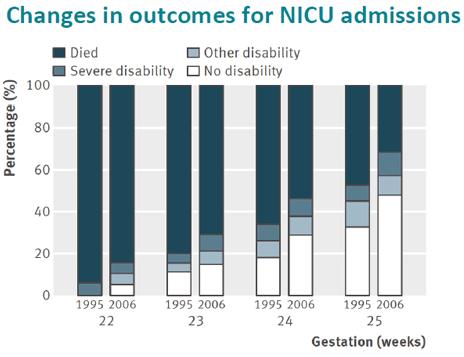

As you can see from the graph there is a huge difference in the odds of survival or disability between being born after 22 and 25 weeks gestation.

Changes in outcome of babies born severely premature in 1995 and 2006 in England (BMJ)

Report author Kate Costeloe, Prof of paediatrics at Queen Mary, University of London, said: "Many of the babies have such a poor prognosis it would not be in their best interests to put them into intensive care. Their lungs and brain and skin are immature, they are very vulnerable to infection and we can't get (intravenous) lines in to deliver the medicine they need."

There is no hard and fast cut-off for hospitals as to when they will intervene and offer what's known as 'active stabilisation'

Neil Marlow, Prof of neonatal medicine at UCL Institute for Women's Health, said: "At 24 weeks we have the presumption that we will do something; at 23 weeks much less so".

Prof Marlow said specialists were split across Europe as to whether they provided active care at 23 weeks. France and the Netherlands do not whereas Sweden does.

Sometimes hospitals take the decision to stop treatment. Prof Marlow said: "About 70% of deaths are elective withdrawals of care. We are trying not to cause harm."

But, improved care means many more premature babies are surviving - especially those born after 25 weeks. There has also been a dramatic 44% increase in admissions to neonatal intensive care, which remains largely unexplained.

Neonatal intensive care costs £1,500 a day, and the average stay is around three months, so the burden on the NHS is huge. Then there are the long-term costs of providing specialist treatment to children. One in five will have a life-long serious disability.

BLISS, the charity for premature babies and their families welcomed the research. Its chief executive Andy Cole said it "emphasises the need for a range of community services to be available to support all premature babies after discharge and the increasing demand for follow up care by paediatricians and other specialists which is not yet being fully met.

- Published5 December 2012