Why taste is all in the senses

- Published

Not everyone experiences the taste of food in the same way.

While some of us reach for a strong coffee in the morning, others recoil. Broccoli and Brussels sprouts may be high on some people's list of favourite Christmas vegetables - but certainly not on everyone's.

The reason why we all react differently to food is not subjective, scientists say. Instead, it is partly genetic and that knowledge is helping them to understand how we use our senses to process flavour.

If you screw your face up at the taste of a lemon and cannot bear sprouts then it is probably because you are a 'supertaster', along with 25% of the UK population.

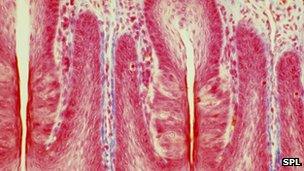

This means you have twice as many taste buds on your tongue as the rest of us - something which makes you particularly sensitive to bitter tastes.

But now scientists have discovered the existence of 'thermal tasters'. These are people whose taste buds react to the temperature of the food on their tongue.

For example, an ice cube will taste salty or sour while anything hot will taste sweet.

Soapy

Another genetic variant means that some people are very sensitive to the smell and taste of coriander. For them, the green herb often found in curries and salads tastes like soap.

Barry Smith, professor of philosophy and director of the Centre for the Study of the Senses at the University of London, says we use all of our senses when we taste food.

Coriander can taste like soap to some people

"How salty or bitter or sweet something is, is to do with how many main receptors on our tongues are firing at the same time.

"You get the smell contributing and the touch, how smooth or creamy it is, and they all fuse together to give flavour."

Smell is a particularly powerful driver of taste, says Prof Charles Spence, from Oxford University's department of experimental psychology. His work on understanding the brain's role in our food preferences has attracted attention from a number of chefs.

Their interest in neurogastronomy is not surprising.

"A big aroma gives you a big flavour hit. Many big companies and top restaurants want to harness that reaction.

"They want to know which product will give rise to the greatest blood flow to the orbitofrontal cortex of the brain."

When the receptors pick up the signal for taste it travels to this part of the brain, located in the middle of the forehead.

Crisp crunch

At a recent Royal Society of Medicine conference, Prof Spence said colour, lighting and ambience could all impact on our perception of taste when eating.

His experiments show that red-coloured food gives an increased perception of sweetness and the colour of the plate the food is on can have an impact too.

Playing music or sounds appropriate to the food we are eating can also accentuate its taste, he says.

Even the sound of a crisp being crunched can influence our view of its freshness, making manufacturers focus on the crunchiest crisp possible.

The more taste buds on your tongue the more sensitive you are to bitter tastes

But knowing how the senses interact to create flavour could have important consequences for public health too.

Prof Smith says it could solve the problem of too much salt being eaten in our food.

"Imagine a clever salt molecule which gives a salty experience in the mouth but puts less salt in the food. It's the future of food science."

Research into the supertaster gene has also found that children may have a reason for being picky eaters.

Children taste bitterness more strongly than adults and are sensitive to the same chemical as supertasters, so it could be that certain flavours taste different to children than they do to most adults.

"Young children get a blast of bitterness in bitter vegetables. Eventually they learn to put the taste and the smell together to make the flavour," says Prof Smith.

Could the supertaster gene be a link to our evolutionary past, warning us off dangerous foods and toxins?

Let's face it, no one likes alcohol or coffee on their first tasting. We all have to learn to love them.

- Published27 November 2012