Polio killings a major setback

- Published

- comments

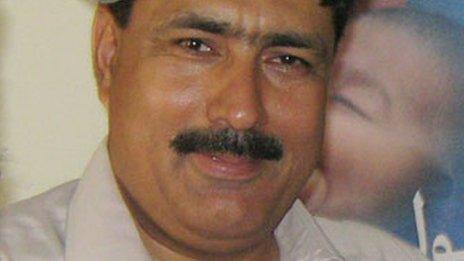

Vaccination is key to controlling the disease

The killing of eight polio workers in Pakistan in two days is a brutal reminder of the hurdles facing health teams trying to eradicate the virus from one of its few remaining strongholds.

Pakistan, along with Afghanistan and Nigeria are the only countries where polio is endemic, which means transmission of the virus has never been halted.

The shootings, in a series of attacks, represent a major setback in the quest for a polio-free world.

The decision by the UN to suspend the immunisation campaign is understandable but deeply regrettable.

So far this year there have been 56 cases in Pakistan, external - a significant reduction on the nearly 200 cases last year.

Unless immunisation is re-started promptly it will allow the virus time to spread and infect more children. It will also risk the disease spreading beyond Pakistan's borders to India, which has been polio-free for more than a year.

The virus is highly contagious and spreads through the faecal-oral route - via contaminated water or food. It can damage the central nervous system causing paralysis and even death.

Karachi - where four female health workers were shot yesterday is one of a number of areas in Pakistan where wild poliovirus is being spread. The others are districts in the Balochistan Province, in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Health officials point out that Pakistan and neighbouring Afghanistan repeatedly re-infect one another due to significant population movements between the countries.

Vaccine myths

Who carried out the killings in Pakistan is unclear but the Taliban have repeatedly denounced the polio vaccination campaign claiming the workers are acting as spies for the US and that the virus causes sterility or HIV/AIDS.

Claims that the vaccine programme is a plot against Muslims have been around for years. They reached their peak in northern Nigeria in 2003 - when the immunisation programme was suspended following claims that the vaccine was contaminated with oestrogen and would cause infertility.

The year-long suspension of polio immunisation led to a major resurgence of the disease in Nigeria with hundreds of children becoming disabled.

When I visited Kano in northern Nigeria in 2005 the authorities had re-started the immunisation programme and religious leaders were voicing their support. But the global impact of the ban had been immense.

Infected travellers had carried the virus to nearly 20 previously polio-free countries causing more than 1200 polio cases.

UN officials in Nigeria told me they had switched to a polio vaccine produced in Indonesia - a predominantly Muslim country - which they hoped would allay any fears about its safety.

The oral polio drops used in the developing world are made from a live weakened virus - which carries a minute risk of causing polio in every million doses given. But the dangers from not being immunised are far higher.

Some of the bizarre myths about the polio vaccine persist in Pakistan, but there are other problems too.

Militants in parts of Pakistan's tribal regions are reported to have said the vaccination programme can't go forward until the US stops drone attacks in the country.

Last year a Pakistani doctor ran a fake vaccination programme to help the CIA track down Osama bin Laden. That has put all immunisation campaigns - especially those with international links - under suspicion.

In a report last month the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative said significant progress had been made in Pakistan in 2012.

Increased pay for vaccinators in some key areas and a drop in the number of parents refusing immunisation for their children were both seen as positive signs.

But the report pointed to an earlier killing of two polio workers as a "tragic and important reminder of the bravery of polio staff".

This is yet another key moment in the battle against polio. The tragic killings in Karachi could have profound long-term consequences for the health of children in Pakistan and beyond.

- Published19 December 2012

- Published23 May 2012