Are the poor kids really the fat ones?

- Published

- comments

Children from poorer backgrounds are more likely to be obese, but was it right for the minister to say it?

Public Health Minister Anna Soubry is no stranger to controversy.

During her four months in the job, she has hit the headlines for comments about "appalling" right-to-die laws and for claiming the government had "screwed up" its reform message.

Now she is back in the spotlight after suggesting you can spot poor children by looking at the size of their waistlines.

According to the plain-speaking Miss Soubry, in years gone by the poor children at school were the "skinny runts".

But as the nation struggles with the obesity epidemic that situation has reversed - with the deprived kids now the fattest, she says.

But is she right?

Well, clearly children from richer backgrounds can be obese, something she herself acknowledged in her comments to the Daily Telegraph when she said her point was more that the greater propensity for obesity lay among the more deprived communities.

And the statistics seem to back her up - to some extent at least.

'Hardly categorical'

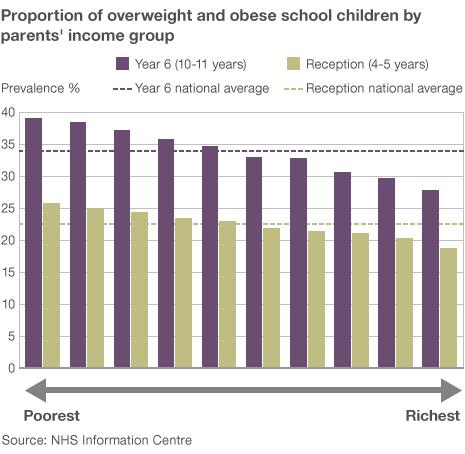

The latest figures show that children from the most deprived 10% of backgrounds were nearly twice as likely to be obese.

The data from the government's child measurement programme, which is carried out in primary schools across England, shows that 12.3% of the poorest reception kids were obese, compared to 6.8% from the wealthiest backgrounds.

A similar pattern emerged among year six pupils - the other age group that takes part in the measurement programme - with 24.3% of the most deprived children obese, compared to 13.7% of the least.

Where the waters get a little muddied is with overweight children that are not quite classed as obese.

Again the children from the more deprived backgrounds are the most likely to be overweight, but by a much smaller margin.

In the case of year six pupils the difference is less than one percentage point.

Perhaps the best thing to do is to combine the two groups, overweight and obese.

When you do that you find about four in 10 children from the most deprived backgrounds are carrying excess weight, compared to nearly three in 10 from the richest.

The gap for reception age children is even closer - one in four, compared to just under one in five.

So while Miss Soubry is right, it is hardly categorical.

In fact, when you look at it another way she could have said you are more likely to be a healthy weight and poor just as you are more likely to be a healthy weight and rich.

But, of course, that would not have been newsworthy.

And perhaps that is the point.

As minister for public health she wants to get people talking and thinking about lifestyle issues.

But has she gone about it the right way?

Experts have mixed views on this.

It is unusual these days to find a minister using such colourful language -and there are some who believe it will harm the drive to tackle obesity.

Tam Fry, from the National Obesity Forum, says it is an "insult" to people on low incomes who are working hard to provide their children with a healthy diet when the odds are stacked against them.

He believes ministers would do better to take a firmer line with industry.

"The government has to be tougher and set limits to the salt, sugar and fat in foods. We are living in an obesogenic environment where it is harder to make healthier choices. Parents have to feed their children."

There are many people who share Mr Fry's sentiments.

But equally some are pleased to see ministers talking so bluntly.

Prof Alan Maryon-Davis, a former president of the UK Faculty of Public Health, has some sympathy with the suggestion that such comments can stigmatise people.

But he says: "By saying what she did in the way she said it she got attention. People start talking about the issue and that is good.

"And it must be remembered she also talked about bad food and industry so I prefer to give her credit."