The battle over alcohol pricing

- Published

- comments

Saskatchewan started using minimum pricing in 2003

Saskatchewan is a long way from the British boozer and the aisles of High Street supermarkets.

But the experience of the Canadian prairie province could have a defining impact on our society.

The region, home to just over one million people, is one of the few places in the world to have first-hand experience of minimum pricing for alcohol.

And as such it is forming one of the key pieces of evidence as ministers weigh up whether to push ahead with what would be a controversial policy.

In England and Wales the consultation on a 45p minimum unit price finishes next week. In Scotland a 50p price has been put forward.

Evidence from Saskatchewan, which has a slightly different policy as there are different minimum prices for different types of drinks, has shown that a 10% rise in price leads to an 8% fall in alcohol consumption.

The findings are backed by Sheffield University experts who have been asked by ministers to analyse what effect a minimum price would have here.

Their work suggests the 45p proposals could cut consumption by 2.4%, which after 10 years would result in 10,000 fewer deaths and more than 300,000 fewer hospital admissions.

But of course it is not an exact science with the researchers admitting they can only give "best estimates".

Predicting behavioural change is notoriously difficult, doubly so when the intervention is aimed at something such as drinking that the public are clearly so attached to.

Unlike smoking where the government can simply say it is bad for you, the message for alcohol has to be much more nuanced as there is no evidence that drinking within recommended levels is harmful and some research has even suggested it may be beneficial to health.

'Compelling'

And this has allowed industry, which unsurprisingly is against the introduction of a minimum price, to claim it is sticking up for Joe Public at a time when household budgets are already stretched.

The Wine and Spirit Trade Association launched a campaign this week called "Why should responsible drinkers pay more?"

Miles Beale, the group's chief executive, is clear he thinks the government is making a mistake.

"Evidence shows that there is no simple link between alcohol price and harm and we do not believe that increasing the price of alcohol will effectively tackle problem drinking."

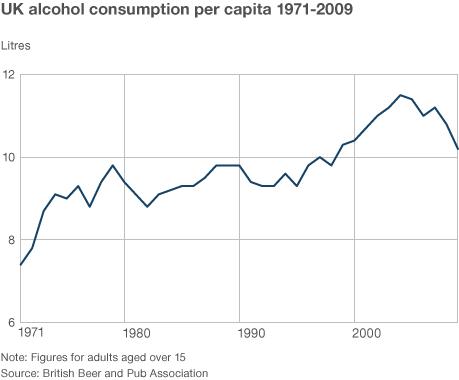

The campaign is also highlighting the fact that alcohol consumption is on the way down in the UK - dropping by 13% since 2004.

That is true, but those who support a minimum price believe drinking rates need to be seen in a much wider context.

While the last few years has seen alcohol consumption tail off, the current figure is still 40% higher than it was 40 years ago.

Where we are drinking has also changed dramatically.

In the early 1970s, 90% of alcohol was consumed in pubs and restaurants, but these days the rise in the availability of cheap alcohol in supermarkets means the split between drinking in and out of home is now almost 50:50.

But to many the clinching factor in support of a minimum price is that the evidence suggests it will hit the problem drinkers the hardest.

As hazardous drinkers are more likely to drink to excess and buy the cheaper alcohol, it is estimated a minimum price would cost them nearly £130 a year compared to just under £7 a year for the moderate drinker, according to the Sheffield University figures.

Dr James Nicholls, of Alcohol Research UK, believes the case for change is "compelling".

In fact, he - like many health campaigners - suggests England and Wales should consider going further and match the 50p put forward in Scotland.

"That is the price at which you begin to affect wine. It would have a much bigger impact."

Ministers certainly have much to consider.