Thriving cancer's 'chaos' explained

- Published

The way cancers make a chaotic mess of their genetic code in order to thrive has been explained by UK researchers.

Cancer cells can differ hugely within a tumour - it helps them develop ways to resist drugs and spread round the body.

A study in the journal Nature, external showed cells that used up their raw materials became "stressed" and made mistakes copying their genetic code.

Scientists said supplying the cancer with more fuel to grow may actually make it less dangerous.

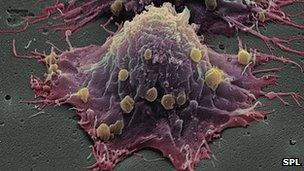

Most normal cells in the human body contain 46 chromosomes, or bundles of genetic code. However, some cancerous cells can have more than 100 chromosomes.

And the pattern is inconsistent - pick a bunch of neighbouring cells and they could each have different chromosome counts.

This diversity helps tumours adapt to become untreatable and colonise new parts of the body. Devising ways of preventing a cancer from becoming diverse is a growing field of research.

Chaos from order

Scientists at the Cancer Research UK London Research Institute and the University College London Cancer Institute have been trying to crack how cancers become so diverse in the first place.

It had been thought that when a cancer cell split to create two new cells, the chromosomes were not split evenly between the two.

However, lead researcher Prof Charles Swanton's tests on bowel cancer showed "very little evidence" that was the case.

Instead the study showed the problem came from making copies of the cancer's genetic code.

Cancers are driven to make copies of themselves, however, if cancerous cells run out of the building blocks of their DNA they develop "DNA replication stress".

The study showed the stress led to errors and tumour diversity.

Prof Swanton told the BBC: "It is like constructing a building without enough bricks or cement for the foundations.

"However, if you can provide the building blocks of DNA you can reduce the replication stress to limit the diversity in tumours, which could be therapeutic."

He admitted that it "just seems wrong" that providing the fuel for a cancer to grow could be therapeutic.

However, he said this proved that replication stress was the problem and that new tools could be developed to tackle it.

Future studies will investigate whether the same stress causes diversity in other types of tumour.

The research team identified three genes often lost in diverse bowel cancer cells, which were critical for the cancer suffering from DNA replication stress. All were located on one region of chromosome 18.

Prof Nic Jones, Cancer Research UK's chief scientist, said: "This region of chromosome 18 is lost in many cancers, suggesting this process is not just seen in bowel cancers.

"Scientists can now start looking for ways to prevent this happening in the first place or turning this instability against cancers."

- Published18 April 2012

- Published21 December 2012

- Published10 January 2013

- Published6 November 2012