Could fitness be key to cancer surgery success?

- Published

Harry Johnstone has been pushing himself hard ahead of surgery

A new keep fit regime might be last thing on the minds of many people diagnosed with cancer - but not Harry Johnstone.

He faced a daunting regime of scans, X-rays, biopsies and five intensive weeks of chemo-radiotherapy.

But with just six weeks to go until surgery Harry is the fittest he has been for years and feeling positive about the outcome.

Inspired by his doctors, Harry is the proud owner of a new exercise bike and sweats it out at home four times a week.

"They kept saying the fitter you are the better you'll recover from surgery so I wanted to be as fit as I can be going into surgery," he said.

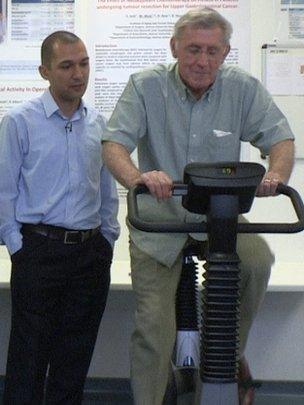

Harry was motivated to buy his bike after taking part in a pilot study at Aintree University Hospital, Liverpool. Patients are invited by Malcolm West, surgical registrar and expert in bowel cancer, to jump on exercise bikes to get into shape for surgery.

"The idea is to try to improve their fitness, their physical fitness, after the downfall they have sustained with their chemotherapy," explained Mr West, who undertook the research at the University of Liverpool's Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease.

The patients in this trial all have stage-three rectal cancer, a form of bowel cancer which requires the most aggressive of cancer treatments: five to six weeks of chemotherapy and radiotherapy to shrink the tumour and major surgery 10-14 weeks later to remove it.

Left at home

It is during the waiting period between chemo-radiotherapy and surgery that Mr West puts patients through their paces on bikes. Usually this time is spent anticipating surgery while fitness dwindles, muscle mass wastes, and spirits dim.

Liz Prichard was discharged from hospital quickly

"Patients are literally left at home to do nothing much, to wait for the treatment to work and then have their operation at 14 weeks," said Mr West.

But in this new regime, patients come in for supervised exercise three times a week for six weeks. It's known as prehab - getting in shape in preparation for major surgery rather than rehabilitating afterwards.

Harry is certainly feeling better.

"I have less problems climbing up hills. I have no problems at all moving about. And I just generally feel a lot better for it," he told Health Check, "I'm hoping this will help aid me for a quicker recovery."

And judging by other patients in the trial Harry might be out of hospital sooner after surgery as a result of his training.

Liz Prichard, another patient in the study, stayed in hospital for only three days after her surgery, a recovery Mr West describes as remarkable.

He said: "We usually have patients staying here for weeks on end."

Liz said: "I actually did the programme properly 12 months ago, more or less January last year. Since then I've had quite serious surgery and then chemotherapy but I've carried on doing fitness all the way through. And I've enjoyed it and hopefully helped myself in the process.

"You know you're doing good for your body so it helps you recover from the surgery. And that's all you can do when you're in this situation.

"It was a commitment but it was well worth doing."

In general the fitter patients are when they go into surgery, the better their chances of a quick recovery. The Liverpool trial aims to find out if a tailored exercise programme and improved fitness after chemo-radiotherapy translates to a shorter stay in hospital.

Chemo-radiotherapy specifically degrades muscle mass, and depresses the function of mitochondria, the tiny structures that act as the boiler room of the cell, generating energy. The theory is that reversing that decline before surgery may help patients be mobile and active afterwards.

"With chemo-radiotherapy you knock the mitochondria function down, hence knocking your muscle activity down. The power output of that muscle is reduced compared to a normal healthy muscle. We're trying to build that back up," explained Mr West.

Big commitment

It is not as simple as encouraging patients to build muscle back up on their own, though.

"We've tried telling patients to join the gym and become more active. However, we've shown that this doesn't work. Patients invariably don't do that and revert to their old lifestyle."

Malcolm West puts Harry through his paces

But Harry travelled 34 miles three times a week to take part in Mr West's exercise sessions. It was a big commitment, but he says he is glad he did it.

"As far as I was concerned I had two personal fitness trainers for six weeks, so it was worth the round trip."

The Liverpool trial is currently at the pilot stage but funds are in place to launch a larger randomised control trial, due for completion in May 2015.

Dr Julie Silver, assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, believes this approach could be beneficial for lots of types of cancers.

She was inspired to found the STAR Programme, a rehabilitation service for cancer patients, after she herself was diagnosed with cancer.

"I got really really sick after treatment and basically was not offered any rehab and struggled to get better and go back to work."

And in summer 2012 STAR started rolling out prehab as well as rehab. Dr Silver is a huge advocate.

"Prehab is a great idea because usually there is the window of time in which someone has been diagnosed, they're very worried and you can utilise that time to their benefit with very specific strategies that help them emotionally and physically. I think of prehab as some sort of umbrella that's offered to patients before they go into the storm."

Malcolm West agrees. "Patients love it. They come in after completing their chemo-radiotherapy in a vulnerable state. They complete their exercise training programme feeling great."