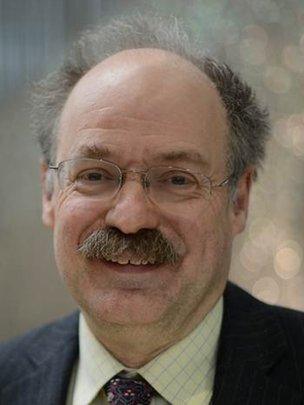

The man who gives away £600m a year

- Published

- comments

Imagine having £600m to give away - every year. That is what Sir Mark Walport has been doing for the past decade at the Wellcome Trust, external.

It is the biggest medical charity in Europe and second in the world to the Gates Foundation in terms of grants.

Since he became director in 2003 the trust has spent £5.6bn on medical research, education and promoting the public understanding of science.

"Our policy is to support the brightest minds - smart people at every stage of their careers - as well as recognising the value of teams. The role of the trust is catalytic - to enable people to achieve advances for human and animal health that might not otherwise happen."

At the end of the month Sir Mark is leaving to become the government's chief scientific adviser.

I met him in his glass office overlooking the Euston underpass in London and asked him to reflect on the past decade.

No doubt what he sees as the dominant scientific advance of the decade - human genetics.

Genome science

It was 10 years ago that scientists announced they had completed sequencing the human genome.

It took 13 years and cost a fortune. Now the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, external - which consumes 15% of the charity's budget - can do multiple genomes each day. The prospect of a £1,000 genome seems not too distant.

So what good has decoding our DNA done for human health? A revolution in the understanding of human disease was promised, with the prospect of more personalised medicines.

"People said it was hyped, but if anything the benefits of the project were underestimated," says Sir Mark.

"It was a decade ago that the BRAF gene was shown, by scientists at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, to be mutated in many patients with the skin cancer malignant melanoma.

"In 2011 vemurafenib was approved - a drug that works solely in patients that carry that mutated gene. That was a direct result of the human genome project."

Sir Mark Walport spoke to the BBC's Fergus Walsh about his highlights in the job

Sir Mark says genome science has also led to improvements in the diagnosis and categorisation of inherited diseases and treatments for inherited forms of diabetes, based on a patient's genetic makeup.

Infectious disease

Microbial genetics is enabling a more precise definition of bacterial, viral and parasitic threats - and how they develop resistance to treatments. DNA sequencing is also enabling disease threats to be tracked as they spread round the world.

"Medical genomics is the technology of the present not the future. Last year we used DNA sequencing to help bring an outbreak of MRSA at Addenbrooke's hospital in Cambridge to a halt.

"It enabled us to track down the staff member who was carrying MRSA, treat them and remove the risk to patients."

The Wellcome Collection, external is a museum on the Euston Road, next door to the trust.

It has been an unexpected hit since opening to the public in 2007, with more than two million visitors. Described as a "free destination for the incurably curious" it has hosted exhibitions on topics as diverse as death, sleep, dirt and miracles.

It also houses the permanent collection of Sir Henry Wellcome, the founder of the trust, who made a fortune in pharmaceuticals.

Sir Henry had a wide and varied interest in health, the human body and artefacts linked to the famous. From Napoleon's toothbrush to George III's hair, Florence Nightingale's moccasins and an iron and velvet chastity belt - it is well worth a visit.

His role will change from chief executive to purely advisory. "It's bound to be frustrating," he says.

"But it's an important job - the interplay between science and the economy is of paramount importance. There will be challenges and opportunities as well as frustrations."

Sir Mark says the security of our energy supply - making sure the lights don't go out and that our infrastructure works - are the obvious challenges ahead. But it is unexpected emergencies which may consume his time.

The man he is replacing - Sir John Beddington - had to provide advice on Japan's Fukushima nuclear accident, Iceland's volcanic ash eruption and the spread of Ash dieback. It's clear then that future threats could come from any quarter.

Perhaps a memento from his time at Wellcome might inspire him in difficult times ahead.

So what exhibit would Sir Mark like to slip into the cardboard packing cases already accumulating outside the door of his office?

"Charles Darwin's cane, external," he says. The walking-stick has a whalebone and ivory top decorated with a carving of a human skull.

"I'd like to have that, but I doubt the museum will let me walk off with it."