Down's syndrome 'linked to brain protein loss'

- Published

Researchers looked at how proteins powered brain function and memory

A lack of a protein in Down's syndrome brains could be the cause of learning and memory problems, says a US study.

Writing in Nature Medicine, Californian researchers found that the extra copy of chromosome 21 in people with the condition triggered the protein loss.

Their study found restoring the protein in Down's syndrome mice improved cognitive function and behaviour.

The Down's Syndrome Association said the study was interesting but the causes of Down's were very complex.

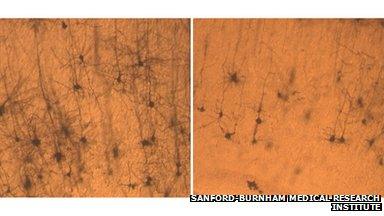

Prof Huaxi Xu, senior author of the study from the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, said that in experiments on mice they discovered that the SNX27 protein was important for brain function and memory formation.

Mice with less SNX27 had fewer active glutamate receptors and therefore had impaired learning and memory.

The SNX27-deficient mice shared some characteristics with Down's syndrome, so the researchers looked at human brains with the condition.

This confirmed their findings in the lab - that people with Down's syndrome also have significantly lower levels of SNX27.

Neurons from a normal mouse (left) are longer and fuller than neurons from a mouse lacking SNX27 (right)

"So, in Down's syndrome, we believe lack of SNX27 is at least partly to blame for developmental and cognitive defects," Prof Xu said.

In the lab, the research team increased the levels of the protein in mice brains to see if the problem could be resolved.

"Everything goes back to normal after SNX27 treatment," said Xin Wang, a graduate member of the research team.

"First we see the glutamate receptors come back, then memory deficit is repaired in our Down's syndrome mice."

But Prof Xu cautioned that science still had work to do to develop a safe technique of delivering genes into the human brain.

Ethical concerns

The researchers are now screening small molecules to look for those that might increase SNX27 production or function in the brain.

Carol Boys, chief executive of the Down's Syndrome Association, said they were following the development of many biomedical research studies into Down's syndrome with interest.

"This particular study is of interest; however, the genetic causes of Down's syndrome are very complex and we are still a long way away from the development of therapeutic treatments that might lead to improvement to cognition in people with Down's syndrome."

She also said they were mindful of the ethical issues that such treatments might raise for people with Down's syndrome and their families.

- Published10 November 2012

.jpg)

- Published5 February 2013

- Published14 August 2012