Big rise in volunteers for medical trials

- Published

- comments

Medical trial volunteers like Gary Bartlett are vital in developing new treatments

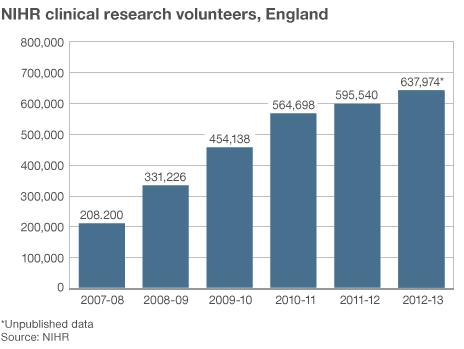

The number of patients taking part in clinical trials in England has trebled in five years.

Figures from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) show almost 638,000 patients volunteered last year.

The rise may surprise some, given the publicity associated with a drug trial at a private research unit at London's Northwick Park hospital in 2006.

That trial - of a potential new drug for arthritis - left six volunteers dangerously ill.

A similar increase in volunteers has occurred elsewhere in the UK.

Although many people associate medical trials with healthy volunteers, the vast majority who take part in research are NHS patients testing treatments for their condition.

The chief medical officer, Prof Dame Sally Davies, said she was delighted NHS patients realised the benefits of participation and said they played a vital role in developing treatments.

The increase follows the establishment of the NIHR in 2006. Its remit is to "improve the health and wealth of the nation through research". The organisation, funded by the Department of Health, has increased the amount of patient-focused health research.

Dame Sally said: "We put between 15-20% patients into trials in cancer compared to 2-3% in the United States, so clearly we've managed to get through to the public to explain the advantages of joining clinical research, and the altruistic side of what they are doing for the people that follow them.

"The doctors and patients have properly funded expert support in the clinic - to help patients understand the meaning of taking part in research, their right to opt out if they do consent - and to help them and hold their hands as they go through the research."

The NIHR has launched a campaign - OK to Ask, external - to encourage patients to raise the subject of clinical research rather than the first approach coming from a clinician. Despite the huge increase in patient numbers on trials, a consumer poll by the NIHR Clinical Research Network found only 6% of those questioned said the public were well-informed about clinical research in the NHS.

Dame Sally also paid tribute to healthy volunteers who tested new treatments. Early trials of medicines are often tested this way.

Permanent damage

In 2006, six men were treated for multi-organ failure in intensive care after testing a new drug in a private research facility at Northwick Park hospital in north-west London. The trial was a "first-in-man" study of a new immunotherapy for leukaemia and rheumatoid arthritis.

The volunteers were injected at intervals of just a few minutes and suffered multi-organ failure. They eventually recovered but have been left with permanent damage to their immune system and other health problems.

The trial had been approved by the MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency). A subsequent inquiry recommended stricter controls concerning treatments that are being tested in humans for the first time.

There are no exact figures for the number of healthy volunteers on trials, as opposed to patients receiving treatment, but it is widely thought that the numbers rose after the publicity surrounding the Northwick Park incident.

"People are usually quite shocked when they hear I'm involved in trials and assume it's high risk, but if you read the literature you know that it's very safe," said Gary Bartlett, an accountant from Oxford.

Typhoid vaccine

He is among nearly 150 volunteers who have been part of a three-year Oxford University trial of a new vaccine against typhoid, funded by the Wellcome Trust. The trial also involved what's known as a "typhoid challenge" where volunteers drink a beaker containing typhoid bacteria to test whether the vaccine prevents the bugs from causing the disease.

Gary developed mild typhoid fever which gave him a flu-like illness and headache. It was treated with antibiotics and did not put him off taking part.

"These trials are so well monitored that you feel well-looked after all the way. You get a couple of days off work - no-one can argue with you if you have typhoid. I also did a trial in London where I contracted malaria but that too was no problem."

Over three years, volunteers on the Oxford trial could earn £3,000. But that involved dozens of visits to the Churchill Hospital and repeated blood tests.

Although the money is welcome, the volunteers I first met 18 months ago seemed motivated more by altruism and an interest in medical research.

Saving lives

"The idea of helping to save lives in countries where typhoid is still a major killer gives you a warm feeling inside," said Mr Bartlett.

Another of the volunteers was Amy Letts, an artist and designer from Oxford. She told me: " They can't test typhoid on animals because it only affects humans. It's a horrible disease so it would be wonderful to get a better vaccine."

Sanitation and a clean water supply helped rid the disease from the developed world. But billions of people in poorer countries are still at risk and it is estimated to claim between 200,000-600,000 lives a year.

Testing the vaccine in Oxfordshire might sound odd, but it means clinicians can control the circumstances in which volunteers are given typhoid. To conduct the same trial in Nepal, one of the countries worst affected by typhoid, would require thousands of volunteers.

Andrew Pollard, professor of paediatric infection at the University of Oxford, paid tribute to the volunteers on his trial at the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre:

"We are trying to develop life-saving vaccines, and that means preventing children dying, especially in the developing world. Volunteers who come forward are saving the lives of children if they help us to develop these new vaccines."

The preliminary results of the typhoid trial are promising but larger trials are needed if it is to ever become a licensed vaccine. From start to finish, the whole process of creating a new vaccine or drug treatment can take 15-20 years and involve thousands of clinical trial volunteers.

- Published24 May 2013

- Published14 April 2011