Avoiding the pitfalls of texting and walking

- Published

The new mobile app warns users about objects in their path

Walking and texting is leading to a spate of collision-related injuries. Could a new app be the answer?

We've all done it. You're walking down the street and the familiar beep of an incoming text becomes too tempting to resist. As you start to fire off a quick reply - bam! You clash shoulders with a fellow pedestrian doing exactly the same.

If you take YouTube as a benchmark, watching unsuspecting texters colliding with lamp-posts and dustbins is pretty hilarious - the modern day equivalent of slipping on a banana skin. But the consequences aren't always a laughing matter.

Alex Stoker is a Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine at Frimley Park Hospital, Surrey. "If it's a tall object like a wall or a lamp-post that someone walks into, then one might expect facial injuries such as a broken nose or fractured cheekbone," he told the BBC.

"If on the other hand the collision results in falling over, then they're much more liable to things like hand injuries and broken wrists. There's a complete spectrum but it is possible to sustain a really serious injury."

Man hole avoidance

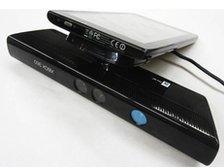

A new app called CrashAlert aims to help save people from themselves. It involves using a distance-sensing camera to scan the path ahead and alert users to approaching obstacles.

The camera acts like a second pair of eyes - looking forward while the user is looking down.

CrashAlert is at prototype stage

Just as a Nintendo Wii or Xbox can detect where and how a player is moving, CrashAlert's camera can interpret the location of objects on the street.

When it senses something approaching, it flashes up a red square in a bar on top of the phone or tablet. The position of the square shows the direction of the obstacle - giving the user a chance to dodge out of the way.

"What we observed in our experiments is that in 60% of cases, people avoided obstacles in a safer way. That's up from 20% [without CrashAlert]," says CrashAlert's inventor Dr Juan David Hincapié-Ramos from the University of Manitoba.

What's more, the device doesn't distract the user from what they're doing. Hincapié-Ramos's tests showed it can be used alongside gaming or texting without any cost to performance.

Dangers on the high street

Although CrashAlert is currently a bulky prototype, collision statistics suggest a final version could prevent a lot of accidents.

A US study in the Journal of Safety Research showed that in 2008 there was a two-fold increase in the number of 'eyes-busy' related accidents compared with the previous year. In other words, people are so busy looking at their phones or iPods, that they stop paying attention to their surroundings.

Walking into walls and lamp-posts can cause a lot of damage (see box). But put a car into the mix and that's where the danger really starts.

Failing to look properly is reported in 59% of car accidents involving the death or injury of a pedestrian.

Kevin Clinton, head of road safety at the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) said: "People should take care not to be dangerously distracted, whether by mobile phones, listening to music or being caught up in conversations with other people.

"Being able to use all of your senses is important when interacting with traffic."

Keeping your eye on the ball

But it's not just looking down at your shoelaces that causes a problem.

"You are also narrowing your field of view because of the attention you are placing on the device." says Hincapié-Ramos. "By doing this, people stop noticing whatever is in front of them and that's what causes a crash."

Research by Prof Kia Nobre, who heads the Brain and Cognition Lab at Oxford University, has shown that despite our brain's huge potential, it can only consciously pay attention to around three things at once.

This may seem surprising, as it can feel as though we are constantly absorbing information from the world around us. But in reality we are focusing on just a few key features.

This is why witnesses to a crime often fail to recall crucial details about what the perpetrator looked like or what they were wearing. In the heat of the moment, our brain simply cannot process what it is seeing.

Red squares show the location of danger

Apply this research to the problem of texting and walking, and it's clear why accidents are inevitable. If you're looking at your phone, then your brain is physically incapable of consciously attending to anything else.

A bit of common sense?

Despite designing CrashAlert, Hincapié-Ramos accepts that the best solution of all is for people to stop checking their phones in the first place.

"We should encourage people to text less while they're walking because it isolates them from their environment. However people are doing it and there are situations where you have to do it. It's for situations like this that CrashAlert can have a positive impact."

But Dr Joe Marshall, a specialist in Human-Computer Interaction from the University of Nottingham, says that it's not necessarily people who are to blame - but the phones themselves.

"The problem with mobile technology is that it's not designed to be used while you're actually mobile. It involves you stopping, looking at a screen and tapping away."

Dr Marshall believes that if we want to stop people being distracted by their phones, then designers need to completely rethink how we interact with them. But so far, there is no completely satisfactory alternative.

"Google glass solves the problem of looking down by allowing you to look ahead. But you still have to pay attention to a visual display," he told the BBC.

So for now at least, it seems vigilance is the key to avoiding lamp-posts and unexpected manholes.

But as mobile technology continues to dominate everyday life, it might not be too ludicrous to expect to rely on smart cameras to steer us in the right direction.