Biting back: Taking the sting out of spider venom

- Published

Ben Tavener discovers how a new way of making anti-venom could save animals' lives

Brown recluse spiders bite more than 7,000 people in Brazil every year causing serious skin lesions and even death. The anti-venom used as treatment comes at the expense of many animal lives. But could a breakthrough in synthetic spider venom lead to a more humane solution?

"The first time I was bitten, I nearly died," says Adelaide Fabienski Maia, a school assistant from Curitiba.

"I put my shorts on in the morning and felt a bite but didn't realise what it was. It wasn't until the evening that my face started burning up. I looked at the bite area and it was red."

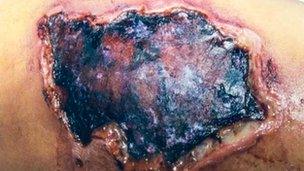

Adelaide was soon rushed to hospital with the classic target-shaped lesion caused by the venom eating away at her skin.

It was only thanks to a dose of anti-venom that she's still around to tell the tale.

But the anti-venom currently available comes with its own risks - mostly to the animals involved in the production process.

Venom is milked from thousands of brown spiders before being injected into horses. This triggers an immune response that creates life-saving anti-venom for humans - while drastically reducing the horses' own lifespan.

Now scientists in Brazil have come up with a synthetic venom alternative that could save many of those lives.

Not so incy-wincy

Brown spider venom kills the skin and leaves horrific wounds

The Loxosceles family of venomous brown and recluse spiders is found in North and South America, Africa, Australia and some parts of Europe.

At 6-20mm long, they are by no means the world's biggest spiders. Even their bite is almost painless. But their venom can cause large sores and lesions through dermo-necrosis - literally "death of the skin".

It is the only family of spiders in the world to cause the skin to die in this way. Scientists have linked it to a rare enzyme in the venom called sphingomyelinase D, which damages and kills skin tissue.

In a small percentage of cases where anti-venom is not administered quickly enough, people can die through organ failure.

But many more deaths - of spiders and horses - are caused through the anti-venom production itself.

"We milk the spiders once a month for three to four months," says Dr Samuel Guizze, a biologist at the Butantan Institute, Sao Paulo's pioneering centre for anti-venom production.

It involves one technician gingerly picking up a spider and giving it an electric shock while a second scientist rushes to draw the venom into a syringe.

As only a tiny squirt of venom is surrendered each time, it means that tens of thousands of individuals must be bred for milking.

"The amount of venom obtained per spider is very small," says Dr Guizze. "We then inject the venom into horses and after 40 days the horses are bled and the antibodies [anti-venom] separated from the blood."

Unsurprisingly, being injected with brown spider venom has an effect on the horses' health over time. Their lifespan is reduced from around 20 years to just three or four.

Sadly, the spiders fare even worse - dying after just three or four venom extractions.

Alternatives to animals

Six hundred miles away at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, a breakthrough in venom technology promises to greatly reduce the anti-venom industry's reliance on animals.

Dr Carlos Chavez-Olortegui is a senior biologist and spider venom specialist.

"We identified the parts of the venom responsible for creating antibodies, and we made a protein chain containing only these parts," he told the BBC.

By making a man-made copy of the active venom ingredient, it means that real spiders could soon be completely superfluous to the process,

And, although horses will still be needed for the foreseeable future, the synthetic venom is non-toxic. This means that horses will still make the right anti-venom in their blood but without experiencing the poisoning effects of being injected with real venom.

Dr Chavez-Olortegui says this new technique will enable horses to be retired after a few years and go on to live a full life

Indeed in the future, he hopes animals can be removed from the process altogether.

A vaccine for the future?

But the study has also shown tantalising possibilities for creating a vaccine.

Trials have shown that animals injected with synthetic spider venom start to produce antibodies that protect them from the effects of real brown spider bites.

Chavez-Olortegui hopes that these results could eventually pave the way for a human vaccine.

"More tests are required to see if the level of immunisation is maintained long-term, but we believe we are on the right path to making a human vaccine soon," says Chavez-Orortegui.

The potential vaccine is seen as a major breakthrough for science but could have only limited applications in the real world - as the cost of developing the vaccine is weighed against the chance of being bitten.

But in a country where 26,000 spider bites were reported in 2012 alone - 7,000 of which involved brown spiders - there could well prove to be quite a demand.

Adelaide Fabienski Maia, who has the dubious honour of living in the "brown spider capital" of Brazil, has since been bitten a second time.

Although they're not naturally aggressive, brown spiders have a nasty habit of sleeping inside people's clothes.

Unsurprisingly, Adelaide doesn't fancy taking any more chances.

"If there were a vaccine, I'd take the whole family today."