Putting a price on life - meningitis B vaccine refused

- Published

- comments

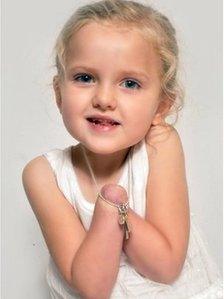

Carys was one of the first babies in the world to get a prototype MenB vaccine in a trial in 2006

Bacterial meningitis is perhaps the most feared of all childhood infections in Britain. It can kill or disable within hours of symptoms emerging.

So it may seem bizarre, even illogical, that the body that advises the government on immunisation should not recommend the introduction of a vaccine against the most common cause of the disease.

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) has decided, external that a vaccine against meningitis B (MenB) is simply not cost-effective.

The vaccine has taken 20 years to develop and was licensed throughout Europe in January. Health committees in France and Spain are also considering the vaccine but no other country has yet recommended its introduction.

The JCVI is the vaccine equivalent of NICE, the body that advises the NHS on new medicines. Given that NHS resources are finite, each committee has to decide whether a new product is cost-effective. This is done by using an internationally recognised system known as quality-adjusted life years (QALY). , external

A QALY is an assessment of how many extra months or years of life of a reasonable quality a person might gain as a result of a treatment.

To be cost-effective, any new vaccine, cancer medicine or heart treatment should cost no more than £20-30,000 for every QALY it saves.

The JCVI has concluded that the MenB vaccine did not meet the economic criteria at any level. In other words, introducing the vaccine would not be a good use of limited NHS resources, which could be better spent elsewhere.

In January a European Commission-funded study concluded that the QALY system of assessing new treatments was flawed.

The announcement from the JCVI will provoke anger and dismay from charities and families affected by the disease. They will argue that the committee has not adequately assessed the appalling lifelong burden of meningitis.

You simply need to hear the story of seven-year-old Tilly Lockey from County Durham to appreciate the appalling nature of meningitis. She lost both her hands and some of her toes as a result of septicaemia - the blood poisoning that can result from meningitis.

Her illness came on suddenly during the night when she was 15 months old. She was initially misdiagnosed as having an ear infection. By the time Tilly was admitted to hospital she was close to death.

"Meningitis is every parent's nightmare. To watch your child suffer like Tilly did was just terrible," said Tilly's mother Sarah Lockey. "If there is a vaccine out there that can prevent another family going through that it's got to be done."

Of course the JCVI is constrained by economic parameters that are ultimately set by the Treasury. If they recommended the introduction of the vaccine, it would mean that some other treatment - perhaps for asthma, diabetes or heart failure - would be rationed.

But given that the drug company Novartis has not yet set a price for its vaccine (trade name Bexsero), how is it possible for the JCVI to conclude that it is uneconomic?

Tilly Lockey

My understanding is that the committee looked at mathematical modelling to work out how much disease the vaccine might prevent and then balanced that against the likely cost of the vaccine and its implementation.

MenB cases fluctuate from decade to decade. We are currently in a trough - there were just over 600 laboratory-confirmed reports in England and Wales last year, compared with nearly 1,700 in 2000.

I am told that even assuming a huge peak of cases and a very low-priced vaccine, the jab did not meet the criteria for NHS cost-effectiveness.

Part of the problem is that the disease is sufficiently rare to make it impossible fully to assess the vaccine's effectiveness.

I followed one of the early trials in Oxfordshire in 2006 involving 150 babies, including Carys. Her mother Karla told me at the time: "Meningitis is the only illness apart from cancer that scares me. It would just put my mind at rest that there is a vaccine which can provide protection against it."

That trial showed the jab was safe and induced a strong antibody response to the meningitis bug. But the disease is sufficiently rare that it could not show how many cases it would prevent nationwide. The only way to find that out is by immunising hundreds of thousands of children.

That is why the JCVI said the available evidence "did not support definitive conclusions about the efficacy of Bexsero". It looks like the vaccine works but until huge numbers of children are immunised against MenB - and some are then exposed to the bug - will we know beyond all doubt.

Catch-22

Furthermore, the vaccine protects against about seven in 10 variants of the MenB bug so it will not completely eradicate the infection.

The other unknown is whether the vaccine will prevent healthy immunised children from spreading the bug to those who have not been vaccinated. That would be a huge benefit.

The vaccine can't be introduced until we know whether it will prevent most cases of MenB. But we won't know that unless the vaccine is introduced.

For Novartis and the researchers who have spent 20 years working on the vaccine, it is a depressing Catch-22 situation. Families affected by meningitis will regard it as a scandal that cost restrictions mean a vaccine-preventable illness will be allowed to go on killing and maiming children.

The JCVI is reluctant to give interviews on this. Little wonder given the flak it is likely to receive from charities, parents and paediatricians.

The director of immunisation at the Department of Health, Prof David Salisbury, did put his head above the parapet.

He said: "This is a very difficult situation where we have a new vaccine against meningitis B but we lack important evidence. We need to know how well it will protect, how long it will protect and if it will stop the bacteria from spreading from person to person.

"We need to work with the scientific community and the manufacturer to find ways to resolve these uncertainties so that we can come to a clear answer."

But at present it is hard to see how those uncertainties can be resolved until a European country introduces the jab.

Britain was the first country in the world to introduce a vaccine against meningitis C in 1999 and it has led to a huge drop in cases.

That was seen as a bold step in protecting public health. But at present it looks unlikely that the NHS will repeat that with the MenB vaccine.