Gadgets 'giving us the lowdown on our health'

- Published

The man who freezes his own faeces

Is it informative or worrying to know in detail what's happening in our bodies? Dr Kevin Fong investigates how information is moving from doctor to patient - and what that means for the management of our health.

There is a famous scene in the movie The Matrix where Keanu Reeves' character, Neo, is offered the choice between a red pill and a blue pill.

The former would open his eyes to the painful truth about the world he lives in, the latter would allow him to remain blissfully ignorant.

We are almost at a stage where we can all make such a choice. But the world waiting to be discovered is not the grim reality of life outside the Matrix; it is the world inside our bodies.

In recent years, consumer technology has become so advanced, so small, and so cheap, that we can now use apps and gadgets to do things we used only to be able to do in hospitals with the help of a doctor.

From your blood pressure to your blood glucose, your oxygen saturation to the number of calories you are burning, we can find any of it out in seconds.

In a few years, there are projected to be 170 million wireless health gadgets in use around the world.

Toys for the boys?

So will the ability to monitor our bodies like this improve our health, or is all this technology just toys for boys?

Until now, most of this stuff has been used solely by gadget-obsessed fitness fanatics, men who want to know exactly how far they have run or cycled, and how high their heart rate has climbed.

But one man for whom this is all much more than a bit of fun, is Prof Larry Smarr, one of the most intensely measured people on the planet.

He gathers as much data about his body as he can by using the standard consumer devices, but he also regularly checks his blood, urine, saliva, and even his faeces, to see what he can learn.

Can self-monitoring change lifetime habits?

This intense monitoring paid off when, a few years ago, Prof Smarr discovered that he had Crohn's disease, a potentially fatal disorder of the intestine. At that stage, he had not even been aware of any symptoms.

Without monitoring himself, he would have carried on as normal, living in blissful ignorance. But instead, armed with information about what was going on inside his body, he was able to change his diet, and give himself the best chance of continuing to lead a normal life.

Prof Smarr believes that in less than a decade, we'll all be able to get the same amount of information about our bodies that he gets from his. But until that point, what can we do?

'The magic 10,000'

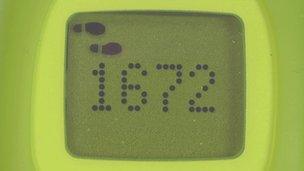

To see how self-monitoring can change things, scientist and presenter Dr Kevin Fong joined three women from Milton Keynes in a little experiment to see how three weeks of measuring their sleep and their activity levels would affect them.

He admits he does far less exercise than he should. Yet a few days after the experiment began, he said that carrying around a pedometer had had an immediate effect.

The recommended daily step-count for people that don't otherwise do much exercise is 10,000.

What's your daily step count?

Dr Fong said: "I didn't really think it was going to change the way I looked at what I did and didn't do, but it really has. It does make you more competitive, even if that's only with yourself."

But he wasn't the only one upping their step-count. Each participant in the experiment started doing more exercise.

As one of them, Pam Brightman, put it, "You can't stop until you've reached that magic 10,000. In a way it's a bit crazy."

Some of the craziest - or more competitive - behaviour was displayed by Celia Walker, who admitted that she "did end up running on the spot while I was watching television, just trying to get those steps up."

'Turning point'

But this wasn't just a pointless exercise in step-counting. There were real benefits. Every participant achieved their ultimate goal during the experiment: they all lost weight.

And by monitoring their sleep, they also found out what affects it, and are all now sleeping better as a result.

The fact is, the more we know about our bodies, the more empowered we are to do things that keep us healthy.

That's why Eric Topol, one of America's leading physicians, is more inclined to ask his patients to monitor themselves than to give them drugs.

In effect, he's prescribing apps. "You name the condition, we get the apps to match up with your phone," he says.

He believes today's technology has brought us to a turning point in medicine.

"This is the biggest shake-up in the history of medicine. It's going to change everything we do in healthcare. Because now all the information is going directly to the patient, not to the doctor. And it's more information than we ever had before."

Whether we really want to know everything that is happening to our bodies, in all its potentially grim detail, is a question for each of us.

And if we do decide we want our eyes opened, it is not a blue pill or a red pill that will help us - it is far more likely to be an app.

Horizon: Monitor Me, is on BBC2 at 2100BST on Monday 12th August

- Published12 August 2013