The enduring legacy of Freud - Anna Freud

- Published

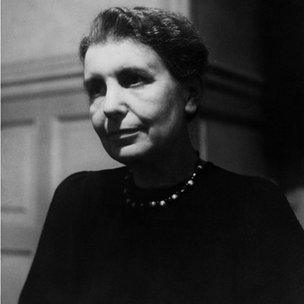

The legacy of Sigmund Freud - the founder of psychoanalysis is well known. But perhaps less so is the impact his daughter Anna had, and continues to have, on child psychoanalysis.

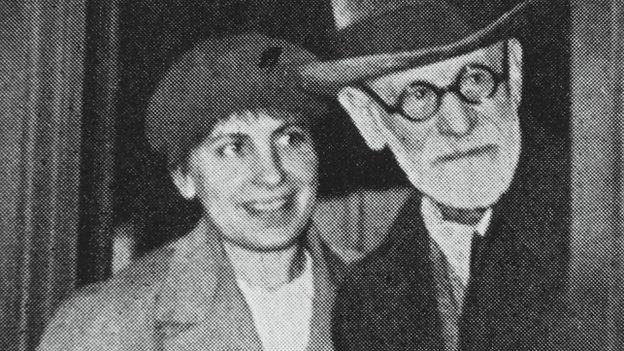

Anna, the youngest of Freud's six children, was the only one to follow in her father's footsteps.

Her involvement began at the age of just 13, when she took part in her father's weekly discussions on psychoanalytic ideas.

Controversially, she is also believed to have received some informal therapy from her father.

By the time of her death in 1982, Anna Freud's work had revolutionised how we treat children in many walks of life, such as in hospital - with longer visiting hours when children are having treatment - and in the judicial system, where screens and video cameras are used when children have to give evidence.

She believed that in order to understand normal behaviour you needed to observe every single move of very young children.

Her staff at a nursery in Vienna - and later, after the Freuds fled from Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938, in London - would write down meticulous observations to try to build a theory of normal development. But they were also trained to think analytically about what might be behind the behaviour.

'Family' units

A centre in Hampstead, north London, that now bears Anna Freud's name, began life as the Hampstead War Nurseries. It opened in 1941 to help around 100 children made homeless by bombing raids.

Freud had trained as a teacher and was influenced by the ideas of the child development pioneer Maria Montessori.

Freud set up the residential nursery because she believed there was a need for a secure environment for the children, whose mothers were busy with the war effort.

According to Dr Nick Midgley, a child psychotherapist at the centre, children were observed working through their issues through their play, as in the case of one boy called Bertie, whose father had been killed in an air raid.

"Bertie would build little houses out of paper and drop marbles on the houses, but each time he played this, at the last moment everyone in the house would be saved. Rather than enjoying the play he was driven to repeat the play," he says.

"And they noticed that it wasn't until he was finally able to actually talk to someone about the death of his father that this play was finally able to shift."

The actor Michael Byrne was just a year old when his unmarried mother took him to the nursery in 1941.

Although initially all the staff looked after all the children, soon Anna Freud introduced "family units".

"We were put into family units of five or six," says Mr Byrne, "the idea being they didn't want us to be institutionalised so you had sisters and you had brothers, then you had this surrogate mother."

His own mother worked for a while at the nursery. Many of those caring for the children had no experience, but Anna Freud felt they would learn from the children.

Mr Byrne says: "They were note-taking. They were looking all the time at the effects this particular nightmare time of war was having on the children."

'Changing with the times'

Dr Inge Pretorius, a child and adolescent psychotherapist now in charge of the centre's parent and toddler service says: "It was during those years that Anna Freud realised the importance of early relationships in future development and early intervention in preventing future difficulties in the child's development."

This approach continues. Ignored by the children, psychology students observe toddlers and the struggles they have when separated from their mother or learning to sit at a table to eat.

Parents at the centre appreciate its approach.

Anna Freud focussed on child psychoanalysis

Jessica, who experienced post-natal depression, takes her 18-month-old daughter, Lily, to the centre every week.

She says: "Everyone needs support after giving birth. You're tired, worried about little things and want to connect with other parents who know what you're going through.

"There's a lot more interaction I think [than other nurseries] - focusing on their development.

"It's not structured either - I find sometimes at groups when there's too much structure, and she doesn't want to fit in to the structure and it causes tantrums. Here she gets full rein of what she wants."

Critics sometimes say that Freud's central idea - of observing children - lacked rigour.

Psychoanalyst Ian Parker says observation can lead the analyst to think that what they see is important rather than what they hear during analysis.

"In psychoanalysis what's most important are the interpretations which are given by the patient themselves rather than the interpretation that are given by the analyst."

But Dr Pretorius says that if you look carefully enough at a child who doesn't even have much language, then speculating on what might be behind it is in fact useful - though subjective.

Mary Target, a director at the centre, believes that there is still a connection with Anna Freud's work - even though its research is progressing in new directions.

"The developmental neuroscience lab is trying to look at areas of brain functioning which are outside our ordinary awareness but which underlie judgements, experiences, reactions, relationships, particularly in very young children and in adolescents, what's going on at the brain level which may help us to understand, for example, whether a traumatised child is able to benefit from a relationship with an adult, depending on whether they feel able to trust them or not."

So what would Freud have made of the new research?

Ms Target says: "She felt that we need to work not just in a clinical way but also through other forms of intervention.

"I would have thought that she would see it as appropriate that we have changed with the times."

Hear Claudia Hammond's account of the life and legacy of Anna Freud in Radio 4's Mind Changers