Alzheimer's breakthrough: Cure or hype?

- Published

If you regularly walk past a newspaper stand, then "Alzheimer's cure" or "Major Alzheimer's breakthrough" headlines will be a familiar sight. And here we are again.

UK researchers have, for the first time, used a chemical to prevent the death of brain tissue in a neurodegenerative disease.

The Times went with Cure for Alzheimer's "within reach", external on its front page, the Independent had Scientists hail historic breakthrough in war against Alzheimer's, external, and my BBC News website article used the headline Alzheimer's find is "turning point".

One major difference this time is that sensible, cautious scientists are suggesting the latest discovery could be one for the history books.

Nearly every report contains this quote from Prof Roger Morris, at King's College London: "This finding, I suspect, will be judged by history as a turning point in the search for medicines to control and prevent Alzheimer's disease."

So what is it about the latest study that generates a rare level of excitement? And is a cure really on the cards?

Significant moment

The prime source of excitement is that a chemical has stopped the death of brain cells, in a living brain, that would have otherwise died due to a neurodegenerative disease.

This is a first and a significant one. When I interviewed Prof Morris on Wednesday night, he used the word "landmark" repeatedly.

In the Medical Research Council study at the University of Leicester, the mice had prion disease, similar to the human form of mad cow disease. Within eight weeks, their brains deteriorated so badly that memory and movement were noticeably affected. By the 12th week, the mice were dead.

But when the same infected animals were given a "drug-like compound", they survived the 12 weeks with no sign of the brain dying. The chemical also caused side-effects including weight loss and diabetes.

The second tier of excitement comes from the potential implications.

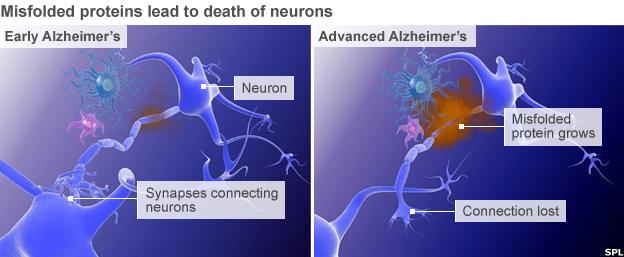

The chemical helps the brain cope with producing broken proteins. In Parkinson's the alpha-synuclein protein goes wrong, in Alzheimer's it's amyloid and tau, in Huntington's it's the Huntingtin protein.

The brain's response to all of these diseases is to shut down protein production, but this eventually kills brain cells. The chemical helps brain cells ignore the broken proteins, keep functioning and stay alive.

In the past, research on neurodegenerative diseases has focused on what is unique to that condition. This approach looks at what is common to all of them and if it really does work, then it raises the prospect of a single drug to cure or prevent nearly all forms of neurodegeneration. Another reason for excitement.

Lead researcher Prof Giovanna Mallucci said: "If it stops brain degeneration in its tracks, it will halt disease in people who have already got it. And if we can detect early disease, it will prevent a lot of degeneration.

"The hope is to arrest the process of brain cell death, and that's what's so exciting."

So where's the cure?

It's worth emphasising the precise findings of the study - a toxic chemical, which the researchers will not even call a drug, halts the death of brain cells in mice with prion disease.

Clearly this is not a cure, but it points the way to one. It gives drugs companies and scientists something to work with.

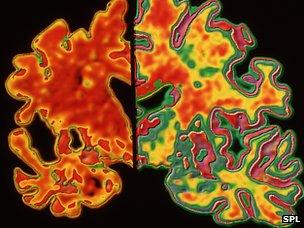

A section of brain with Alzheimer's disease on the left shows the marked loss of brain cells

That process will take time, probably more than a decade, with no guarantee of success at the end.

And the recent history of medical research is littered with examples of drugs that looked promising in mice, but were a bitter disappointment when tested in people.

This chemical works in a mouse brain of 75 million neurons. A more complex human brain built from 85 billion neurons is a far different challenge.

Dr Simon Ridley, the head of research at Alzheimer's Research UK, told the BBC patients would be facing a long wait.

"I'm afraid it's far longer than any of us would like," he said.

"I think there are many people who'd be desperate for any news of new treatments, which they would like to take today.

"I think at this stage we could be looking at a decade before we'll know whether this will be effective."

This study is certainly exciting scientifically. But it might take until 2023 to see whether it truly deserves its place in the history books.

- Published10 October 2013