Why women feel 'stigmatised' for not having children

- Published

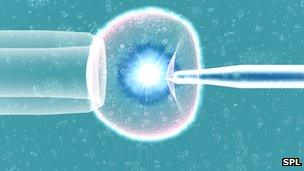

It is never too early to talk to a health professional about fertility worries

New research suggests that many women aged 35-45 who do not have children feel judged for not having had a baby.

Even if they plan to have a child, nearly 60% have at some point felt stigmatised for leaving it late.

About 40% are too embarrassed to talk about fertility, especially with family and friends, often the biggest source of pressure.

Susan Seenan from Infertility Network UK says this prevents some women from seeking help for fertility problems.

The organisation, which interviewed 500 women for its survey, said it was a common problem.

"Trying for a baby is a very personal thing which people don't always want to talk about, but there is constant pressure from families saying 'Isn't it about time...?'," said Ms Seenan.

"And if you don't say anything, then friends and family assume you like your lifestyle too much to be bothered about children."

If women are then diagnosed with fertility problems, the sense of isolation can become even worse, she says.

"Unfortunately, infertility is still a taboo subject. When women are labelled as infertile they feel a failure, because they have let themselves and their partner down.

"Their basic biological instinct to have a child is kicking in - and at that point everyone seems to have babies, but they can't."

Ms Seenan suggests that for women in this position, it is easier to talk about mental health problems than infertility problems, which is the reason behind the forthcoming National Infertility Awareness Week.

Hurtful

Neela Prabhu, 36, from London, knows how hard it is to spend years trying to become pregnant. She and her husband tried for over a year before seeking help, and that took its toll on them both.

The success of IVF depends on a woman's age

"My mental state at the time wasn't great and although some friends tried to be well-meaning, they kept saying unfunny things about our situation. They were trying to be helpful but sometimes it just hurt. All I could think about was having a baby."

Neela's parents are from India and are very supportive, but she says her mother couldn't relate to her problems, partly because it is an issue rarely discussed in Asian communities.

She says she wants this to change.

"I want there to be more openness. I want women to talk about infertility even if they are dying inside, and I want to give women the confidence to talk about the journey of having a child.

"But it just seems to be a taboo subject - why should this be?"

Neela finally had a daughter four years ago after IVF and has recently discovered she is pregnant again with her second baby, following two failed cycles of IVF last year. She has never found out the cause of her fertility problems despite numerous investigations.

Neela started trying for a baby at 27, but many women leave it much later and by doing so they decrease their chances of conceiving naturally and risk missing out on treatment under the NHS.

'Fallback solution'

Current guidelines recommend that women up to 39 should be offered three full cycles of IVF and women aged between 40 and 42 should have access to one cycle.

But there are huge variations in criteria across the UK. In Oxford, for example, 35 is the limit for IVF treatment on the NHS.

Tim Child, medical director at the Oxford Fertility Unit at the University of Oxford says people are leaving it too long before before going to see their GP about their fertility problems.

"When couples start talking about their fertility, that's the point to speak to a healthcare professional.

"Good advice can be given early on about weight, diet, alcohol intake etc which could help, but many couples try for years before seeking help and before they know it they are in their late 30s - and in some areas that's too old."

He says that women wrongly assume that IVF is a good fallback solution when in fact the success rates are 40-50% for the under-35s, dropping to 20% for the under-40s and just 5% for women aged up to 43.

Neela hopes that people can be more understanding and supportive towards women "who can't just fall off a log and get pregnant" so that people like her can feel more comfortable talking about it.

Instead of asking personal, intrusive questions, she wants people to be aware that one in seven heterosexual couples in the UK is affected by infertility.

Being judged has made Neela speak out.

"People used to ask me, 'Don't you want another child?' It's really nobody's business but mine."

National Infertility Awareness Week runs from 28 October.

- Published20 February 2013

- Published2 July 2012

- Published8 July 2013