Baby steps to saving lives

- Published

The patter of tiny feet: but how small is too small?

Each year, one in 10 babies around the world will be born prematurely and over a million of those will die. But could measuring the size of a baby's feet help save lives?

In the final weeks of pregnancy, the idea of going into early labour might not seem like such a bad thing.

But giving birth prematurely - officially classed as before 37 weeks gestation - can lead to long-term health effects.

Depending on quite how early the baby is born, infants can either be completely unaffected or left with permanent disability and learning difficulties.

The issue of prematurity is particularly pronounced in South Asian and Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for over 80% of the deaths caused by pre-term birth complications.

In rural Tanzania, for example, about one in every 30 premature babies won't make it past four weeks.

However, most of those lives could be saved with simple advice for mothers.

And that advice, says an international group of researchers, could start with just a footprint.

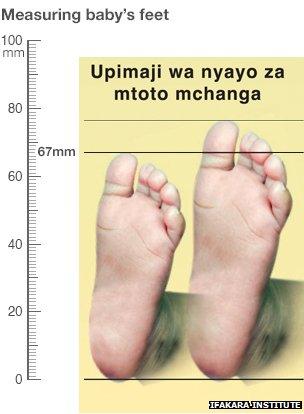

The larger foot on the yellow card represents a full term baby's foot size. If a newborn's feet are smaller than the small foot on the card, the baby is probably premature and the advice is to take the baby to hospital immediately. Side rule added for scale.

Sizing up

Most mothers in high-income countries will give birth surrounded by medical equipment or with the support of a highly-skilled midwife.

This means that any problems, such as a low birth-weight or the mother's waters breaking early, can be dealt with immediately.

In contrast, around 40% of women giving birth in low-income countries will do so without the help of a trained medical professional.

And due to inaccurate dating of pregnancy, many of those women will have no way of telling if their baby is too early or too small.

However, measuring the baby's footprint could be used as a simple proxy for birth weight.

"There's this grey area when the baby is between around 2.4kg (5lbs 5oz) and 2.1kg (4lbs 10oz) when the baby is more vulnerable to infection and other issues," says Dr Joanna Schellenberg of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

"But when a baby is born at home, there is no way of weighing them," she told the BBC.

The BBC's Tulanana Bohela has been to see the project in action

To help solve the problem, Schellenberg and her colleagues at the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania have implemented a strategy called Mtunze Mtoto Mchanga - which means "protect the newborn baby".

It includes using a picture of two footprints on a piece of laminated card and a local volunteer placing the baby's foot against the images.

If the baby has feet smaller than the smallest foot, around 67mm, then the mother is advised to take the baby to hospital immediately. If it measures in between the big and the small image, then the mother is told about the extra care she needs to provide to increase the baby's chances of survival.

Although the card is fairly accurate for five days after birth, it should be used it to identify small babies in their first two days of life, which is when they're most at risk of dying without specialist care.

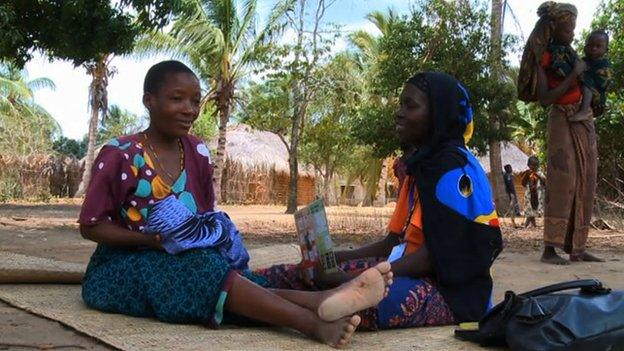

Mariam Ulaya is one of the volunteers at Namayakata shuleni village and visits the women before and after the birth.

"If I've measured the child's footprint and seen that the child is smaller than usual, then I instruct them to carry the child skin-to-skin so that the child can share and feel the mother's warmth," says Ulaya.

"I also carry a small doll with me called Opendo. I use the doll to illustrate the proper way to breastfeed the child."

'It has helped my child to survive'

Such advice may seem simple but can really be the difference between life and death.

A report, external by the World Health Organization (WHO) says that of the 15 million premature births globally each year, more than 80% will occur between 32 and 37 weeks' gestation.

Most of these babies will survive if given extra warmth through skin-to-skin contact and very regular breastfeeding to help fight off infection.

In fact, the report states that an estimated 75% of deaths in preterm infants can be prevented in this way - without the cost and emotional upset of intensive care.

Salima Ahmad is 25 and has three children who live with her in Namahyakata dinduma village, Tanzania. Her youngest son, Alhaji, was born prematurely.

"I was a little bit shocked because many premature babies end up dying but I was also happy because I had a live baby," says Salima.

Although Alhaji was born at the local hospital, Salima was given advice and support by volunteers from Mtunze Mtoto Mchanga about how to care for him once she got home.

"Carrying skin-to-skin was good but difficult in the beginning. But when the volunteer was visiting me and encouraging me, I could see myself managing it slowly. It is good, it has helped my child to survive," she says.

Salima also feels that understanding more about premature birth helps mothers like herself to deal with it properly.

"It helps a lot for the mother not to be surprised when having a premature birth. It is useful to know in advance as you get good knowledge on how to handle the premature. Myself, I do thank the volunteer who talked about it when I was pregnant and she even taught me how to carry skin to skin."

Saving lives

Local volunteers are key to sharing knowledge about caring for preterm babies

The project is still underway and it will take another six months before it's clear whether measuring feet has the ability to save thousands of lives.

However, it is already having a positive effect on the way mothers in the area are preparing for childbirth.

"When I had my first child, she was small and was not breastfeeding well and I did not know where to get help," says Rukia Twarib, who is currently pregnant with her second child.

"Now I have information, if the situation ever happens again, I know can go to the health centre to get help."

Advice from volunteers like Miriam also appears to be contributing to the increase in women now choosing to deliver at a health centre rather than at home.

Dr Isa Lipupu works at the nearby Nangururwe health centre.

"In the last two years, we had about 20 deliveries at the health centre. But this time we have already delivered more than 40 babies. This is about 60-80% of all the mothers that were pregnant," he says.

If the strategy proves successful, then there are already plans to roll out the footprint scheme to the rest of Tanzania, giving more health volunteers the ability to quickly spot at-risk babies.

"Right now many people are aware of the work I do. All the families have been very welcoming and have accepted me and this programme," says Mariam Ulaya.

"I have seen a lot of changes in the area. I can see that there are more mothers visiting the clinic and giving birth there - much more than they used to do - and so I am grateful for that."