Will changing cigarette packets reduce smoking?

- Published

Cigarette packaging is back on the political agenda in England.

The government decided against introducing standardised packaging in 2012 saying it wanted to wait until evidence emerged from the first country in the world to introduce such legislation - Australia.

A year later, it has now launched an independent review with the possibility of uniform packaging being introduced in 2015.

When did governments start to curb smoking?

This debate is all a far cry from the early days of cigarette advertising. It was a world of sex appeal, Hollywood and the Marlboro man.

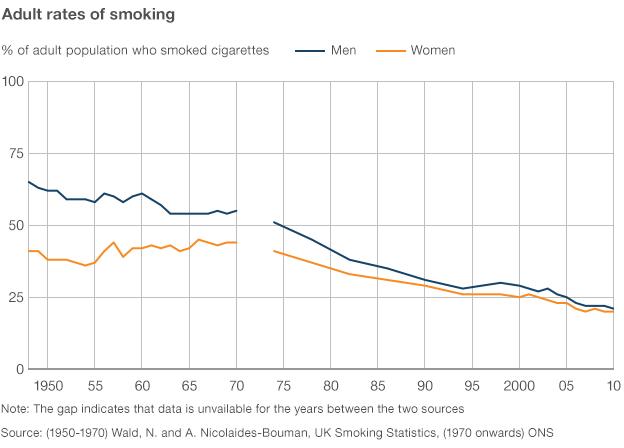

At first, it was mainly men who smoked, but women joined the club in large numbers after World War Two.

But then the image of smoking began to change as the deadly consequences of tobacco-use emerged.

A report by the UK Medical Research Council in 1957, external, followed by one from the Royal College of Physicians in 1962, showed a direct link between smoking and lung cancer.

This spurred governments around the world into action.

Archive: Smokers in 1962 react to the report

Have tobacco companies lost the advertising war?

Smoking was once heavily advertised and enjoyed a close relationship with major sporting events including Formula 1.

Adverts for cigarettes were banned from British television in 1965 and a complete ban on all forms of tobacco advertising was introduced in phases by 2005.

At the same time, the European Union introduced a ban on all tobacco advertising and sponsorship, external across all media.

Commercials on Australian television and radio were banned in 1976 while newspapers followed in 1989.

It is why the humble cigarette packet is at the centre of such fierce debate. In many countries, it is the last place where manufacturers can advertise their brand.

How effective have other measures been?

Remember the days when you could smoke inside a pub while having a pint, or at your desk at work?

New York banned smoking in restaurants, bars and clubs in 2003. France, India, Ireland and Italy rapidly followed.

Between 2006 and 2007 the UK also banned smoking in enclosed public spaces such as bars, restaurants and workplaces.

The ban has been described as "one of the most important public health acts in the last century" and studies have suggested lower rates of heart attacks and asthma since the ban.

A Department of Health-funded study examining emergency admissions between July 2002 and September 2008 in England found a 2.4% reduction in admissions for heart attacks.

Research from Scotland reported a much larger 17% decrease in heart attack admissions in the year after its ban while another study found a 10% drop in the country's premature birth rate, which researchers linked to the smoke-free laws.

However, smokers' groups say the ban has been a disaster for many pubs and clubs.

Do gruesome pictures work?

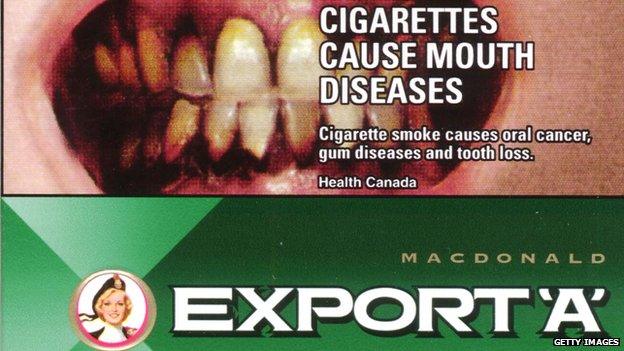

Packets in Canada come with graphic health warnings

Graphic pictures on cigarette packages showing the dire health consequences of smoking are another tool used to dissuade people from smoking.

Black-tar filled lungs, tumours and diseased rotting teeth are now a fixture on cigarette packets in some countries.

Canada led the way in 2001 and was shortly followed by Brazil and Singapore.

A study suggested the policy in Canada cut smoking rates by between 12% and 20% from 2000 to 2009, external.

The World Health Organization argues, external that the pictures "significantly enhance the effectiveness" of warning labels.

Some countries move the packets out of sight and keep them below shop counters.

What did Australia do?

On 1 December 2012, Australia formally introduced uniform packaging dominated by health warnings.

All tobacco company logos and colours were banned from packets. The only concession to the tobacco industry was that the name of the brand was allowed in small print at the bottom.

"This is the last gasp of a dying industry," declared Health Minister Tanya Plibersek at the time.

Ireland is planning to follow suit and Scotland also has its own plans to introduce plain packaging.

What impact has it had?

Early findings from Australia, published in the British Medical Journal, external, suggested the move made smoking seem less appealing and increased the urgency for people to quit.

During the transition from glitzy to drab packaging, the research showed those smoking plain packaged cigarettes were 81% more likely to have thought about quitting and 70% more likely to say they found the cigarettes less satisfying.

But this will not be the measure of success for plain packaging.

The big questions - has it cut smoking rates? Are fewer children taking up the habit? We still do not know.

Why is England lagging behind?

Initially the government had seemed keen on plain packaging as a way to reduce smoking rates.

A consultation by the Department of Health, external had shown that the debate was "highly polarised" with "strong views" about the effectiveness of the policy on both sides.

Officially the government line was to assess the impact of legislation in Australia.

However, this attracted criticism with Labour describing it as a "humiliating U-turn" and continuing to draw attention to the Conservative election chief Lynton Crosby who worked as a consultant for the tobacco industry.

Paediatrician, Sir Cyril Chantler, will lead the government's review and will report by March 2014. The findings could lead to a change in policy before the 2015 general election.

What is the long term trend in smoking in the UK?

- Published28 November 2013