Malaria: The dangers of not taking anti-malaria tablets

- Published

Mandy had stopped taking anti-malarial tablets while working in Haiti

Last Christmas saw Mandy George in a coma in a Dominican Republic hospital.

Her mum and brother had flown to her bedside, and were praying she would fight off the malaria parasite that was attacking her organs and sending her body into septic shock.

"Everything that could go wrong in my body went wrong," she says.

After living and working in Haiti for more than two years, she had stopped taking anti-malarial medication.

Recovering in hospital with some of her medical team

No one else she knew there was taking it and she had heard people say that the medication was harmful when taken long-term.

That information was wrong, and the decision nearly cost Mandy her life.

It was while on holiday in the Virgin Islands, just a week earlier, that 33-year-old Mandy started to feel unwell with a fever and some very intense headaches.

Instead of getting medical advice there, Mandy waited until she returned home to Haiti a few days later, and by then she "felt horrific".

"I collapsed. I begged a friend to take me to hospital, where I spent the night, and then in the morning I started to have liver failure and got pneumonia," she says.

'A swollen carrot'

Doctors in Haiti realised treatment in the nearby Dominican Republic was the best option and she was flown straight to an intensive care bed.

By this time her liver and kidneys had failed, she had swelled up to twice her normal size. Her skin had also turned a yellowish-orange colour, making her resemble "a swollen carrot".

She also needed blood transfusions and dialysis.

The worst part for Mandy, however, was the sensation of drowning caused by her lungs filling up with fluid.

"I was gasping for air even though there was air all around me. They were trying everything to make it better.

"I had all sorts of contraptions on my face, medication to inhale, balloons of air pumped into me. But nothing worked."

It was then that doctors decided to induce a coma. Mandy doesn't remember much of this time, although some images do stand out.

"I was so ill I didn't have the energy to be afraid. I felt quite calm, although I kept telling them I couldn't breathe.

"I saw my friend with tears in her eyes and the doctor standing with his arms crossed staring at my monitor.

"I remember thinking - 'I could die here'."

Deaths

Mandy wouldn't have been the first UK national to die from malaria.

In 2010, more than 1,700 travellers were diagnosed with malaria after returning to the UK and seven of them died. In 2012, two people died of the disease in the UK.

Last month a woman from Lancashire died after contracting malaria on holiday in the west African country of The Gambia. She had not taken anti-malaria tablets either.

Mandy says she survived thanks to the fantastic care of the medical staff in the Santo Domingo hospital - and one particular doctor who made it her mission to make sure she beat malaria.

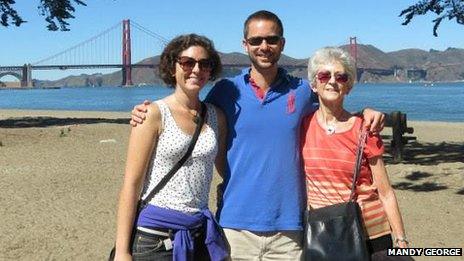

Mandy visited San Francisco with her family after her health improved

In the end, she spent one month in intensive care and several more weeks in a wheelchair while urging her weak legs to walk again.

After several weeks of communicating by writing notes, because a tracheostomy tube had been inserted in her windpipe to help her breathe, she was finally able to talk again too.

It was fully six months before she returned to normal, and by that time she had returned to the UK and was recuperating at her parents' home in Lincolnshire.

"I was very lucky", she says. Doctors are always telling me, 'Wow it's amazing you are still alive!'. I feel very grateful and fortunate to be here now," she says.

The fact she was young, fit and healthy was probably a factor in her recovery, but she is still very aware of how close she came to succumbing to the parasite.

Mandy also has some important advice for others before they go abroad.

"Don't travel anywhere if you think you have something seriously wrong with you, get tested immediately you think there's a problem, and low risk doesn't mean no risk.

"I'm an intelligent person - but I had no idea how serious malaria could be."

- Published28 November 2013

- Published18 October 2011