Middle East attempts to ward off scourge of polio

- Published

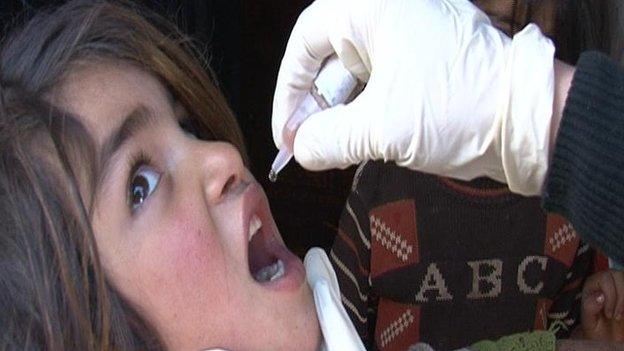

Vaccination campaigns have been stepped up

It's just a drop in the mouth but it's the drop on which high hopes are pinned, universally.

Only vaccination can prevent infection with poliomyelitis (polio), a viral and highly contagious disease that paralyses children.

It was close to being eradicated worldwide, but has re-emerged in several parts of the world, most recently in Syria.

The outbreak sent shockwaves around the region, especially across Syria's western border in Lebanon, where an intensive vaccination campaign was launched.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the first cases of polio in Syria were reported last October in the eastern province of Deir al-Zour, 14 years after Syria was declared free of the disease.

BBC News outlines the struggle against polio - in 60 seconds

The latest WHO update says that 17 cases of polio have been confirmed in Syria - 15 of them in Deir al-Zour, one in rural Damascus, and one in Aleppo.

The news prompted strong reaction across the region, the fear of the virus spreading focusing minds.

But for some experts, it should have all been anticipated, and perhaps prevented.

"It was of no surprise to public health and medical practitioners in the region that a communicable disease outbreak such as polio would eventually occur in Syria," said Dr Adam Coutts, a public health researcher based in Lebanon, who has been monitoring the health situation in Syria for 18 months.

"Questions remain as to why WHO did not better prepare for this, given their own recognition about the risk of outbreaks."

It is not the first time that the virus has reappeared in regions that were previously declared polio-free: in 2011 the virus spread from Pakistan to China.

However, Oliver Rosenbauer, a WHO spokesman in Geneva, said the immunisation operations were more complicated than they appeared, despite the WHO having access to all areas in Syria since 2010.

He said: "It's about the nature of the disease that spreads with moving populations that makes it so hard to contain it. The virus is really good in finding susceptible children.

"In places of high risk like Syria, immunisation campaigns alone are not sufficient. A better level of routine vaccination and monitoring is required, and this is very difficult in dangerous areas."

Regional emergency

The global eradication plans should not be dented as long as efforts continue in the remaining endemic countries and outbreaks in other countries are halted.

But far from being just another Syrian crisis, the outbreak of polio is considered as a regional emergency in the Middle East.

Large vaccination campaigns have been launched in Jordan, Egypt, southern Turkey, Iraq and Lebanon.

Rajesh Mirchandani visits the polio vaccination programme in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya

All these countries have taken a large number of Syrian refugees - but none took as many as Lebanon.

Large numbers of Syrians enter Lebanon every day, and the chances are high that an infected child could pass it on.

Insanitary and crowded conditions, coupled with low immunisation rates, decrease the odds.

The Lebanese authorities and international organisations have pledged to vaccinate all children under five on Lebanese soil.

Schools, nurseries and medical centres have all strived to reach every child in the country but it is a difficult task.

Authorities estimate that more than a million refugees live in Lebanon but there is no official database about their whereabouts or movement in the country.

The most difficult to reach remain those living in tented settlements.

There are more than 100,000 of them and they are spread all over the country, wherever they find an empty spot of land on which to erect their tent.

Reaching this group is often a matter of chance.

"We're trying to get to each and every child among the Syrian refugees but we constantly discover new mini-camps hidden in one place or another," said Dr Melhem Harmouch of Beyond, an organisation working in partnership with Unicef.

"Every time we spot a new settlement, we just pop in and ask whether the kids have been vaccinated."

'No strategy'

But polio is just one of countless health problems from which Syrian refugees, like some Lebanese, are suffering.

"The whole health system is collapsing, and there is no health strategy for the refugees," said Dr Fouad Mohamad Fouad, a Syrian physician and professor of public health at the American University of Beirut.

Some are concerned that polio has too high a profile

"Polio is somehow fashionable these days, so everyone is so concerned about it. But other illnesses are also dangerous and totally ignored."

Dr Fouad said there were countless numbers of refugees suffering from cancer in Lebanon.

"What about those with diabetes, or those with kidney problems who need regular dialysis? What about those with heart problems or the disabled? And who's taking care of the people with mental problems?"

The UNHCR offers a range of treatments for the refugees but is unable to expand the coverage to specialist healthcare assistance for all chronic disease. In Lebanon, medical care is mostly private and expensive.

"Syrians who are internally displaced and refugees have been dying and disabled in far greater numbers for the past two years and from conditions other than polio or infectious diseases," said Dr Coutts.

"War injuries, chronic and non-communicable diseases are silently killing Syrians without much media attention."

Or, as Dr Fouad puts it: "I guess media and the world are much more interested in gory deaths than in latent and slow ones."

- Published19 December 2013