Nystagmus: Looking for answers to eye disorders

- Published

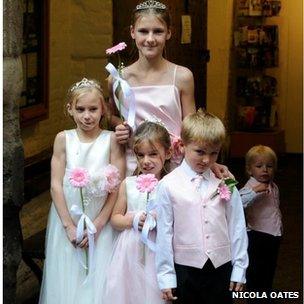

Thomas has had one operation to improve his vision

Nicola Oates always thought her son Thomas's clumsiness as a baby was normal.

As he got older, it became more problematic. He would trip over anything lying on the floor and he started falling behind at school. He also developed a habit of turning his head to the right, and pointing his chin downwards, when looking at something.

"That was very odd," says Nicola, who lives in the Midlands. "He looks normal most of the time but when he focused his eyes he wanted to look out of the top of his head.

"When he was walking he'd end up bumping into walls, chairs, people... everything."

It was Thomas's way of "stopping his eyes swinging" she explains, a symptom of an incurable eye movement disorder called nystagmus, external.

Referred to as "wobbly eye" because it causes uncontrolled eye movements, nystagmus also creates lots of problems with vision.

Strobe vision

Jay Self, paediatric ophthalmologist at Southampton General Hospital and a senior lecturer in ophthalmic genetics at the University of Southampton, says it is vitally important to find out more about the disorder because one in 1,000 people is affected in the UK.

Thomas developed a head-turn to see more clearly

"It can be very disabling, it can affect someone's whole life which could be 80 to 90 years, their working life, families and future generations."

He describes having nystagmus as "like seeing the world in strobes", leaving children struggling to see moving objects and slow to recognise faces.

According to John Sanders, from support group Nystagmus Network UK, few adults with nystagmus can drive and most encounter some difficulties in every day life, education and employment.

Sufferers can have problems in many social situations too, because they miss facial cues, but these difficulties are not always picked up by standard eye tests and the true extent of their vision problems are never fully investigated.

Thomas, for example, who is now eight, is not classed as visually impaired or partially sighted because he can read an optician's eye chart.

Despite this, he needs visual aids, such as magnifying blocks and lights, to help him read and he needs a handrail to help him get round the house.

At home, he wears glasses with blue tinted lenses to protect his eyes and by 19:00 he's exhausted with the effort of trying to see properly all day.

Nicola says: "It's very hard for him. He can't judge how far away things are. Even when he hugs me he has to stand on my feet to find out where I am."

Tailoring treatment

At Southampton's new research centre for children with eye problems, Mr Self has already started analysing hundreds of genes to discover more about what causes congenital nystagmus, which appears soon after birth.

His aim is to develop a simple genetic test for children with nystagmus, which will allow them to be diagnosed quickly and accurately.

He also wants to use real-world visual functioning measures - rather than eye tests - to measure the actual visual problems caused by the disorder.

This will mean children can receive specific, tailored treatments.

Thomas's mum is fighting for the help he needs

Even without these new treatments, Mr Self says there are some simple steps which can help schoolchildren with nystagmus. They include getting the support of a visual impairment teacher and sitting the child on the side of the classroom which suits their field of vision.

Thomas's eye movements were picked up by a relative when he was around eight months old but it wasn't until he was five that he was referred to his local specialist centre for treatment.

He had an operation to improve his eyesight a year ago and will probably have another later this year.

His mum Nicola has noticed improvements, but he still turns his head to see where he is walking.

"I don't know how bad his vision really is because for him it's just normal, he was born with it and doesn't know any different."

But she has realised it is up to her to fight for the help he needs.

"I've decided to ask more questions and stand up for him. Why should he struggle? He deserves more..."

- Published5 October 2013

- Published16 January 2013

- Published14 May 2012