Why Oxford scientists are experimenting on monkeys

- Published

- comments

See inside the Oxford animal laboratory

The macaque in front of me has a choice. Two differently coloured images have been slid in front of her cage.

She taps the purple picture and gets a treat. The next time she taps the black image. On this occasion not only does she get a reward, but a second monkey facing her does too.

This is an experiment in social decision-making, looking at the impact that our choices have on others. It's something humans and monkeys do every day.

The monkeys appear relaxed and interested - possibly more intrigued by me and my cameraman than the prospect of another nut or date.

We are in the Biomedical Sciences building, also known as the Oxford animal laboratory.

Human volunteers

The researchers, led by neuroscientist Prof Matthew Rushworth, are exploring the way neural networks vary between human and monkey brains.

Oxford has 23 macaques housed in pens like these

"About two thirds of the work we do is with human volunteers but the important thing about the animals is they allow us to manipulate in very precise ways some of these circuits."

What this means is that some of the monkeys have had small lesions - areas of damage - made in part of their frontal lobe. This is something that couldn't be done with human volunteers. It allows the scientists to examine what happens when specific areas of neural network - the wiring in the brain - malfunction.

"This gives us key insights into how some of these areas are going wrong in psychological illnesses such as depression, but it can also apply to disorders like autism," says Prof Rushworth.

A rare glimpse into a controversial area of medical research

But while humans and monkeys are both primates, the brains of macaques are far less well developed. Prof Rushworth's team, whose work is funded by the Wellcome Trust and the MRC, have published research in the journal Neuron , externalcomparing MRI scans of human and monkey brains.

"We found that many of the neural circuits involved in decision making were similar in humans and monkeys," said Prof Rushworth.

"But there were unique areas in the human brain, including one which allows us to put a value on the choices we don't take - this enables us to make more sophisticated decisions than monkeys."

Although some aspects of cognition are unique to humans, the Oxford team, in common with other neuroscientists, believe primate research can give important insights into many human disorders.

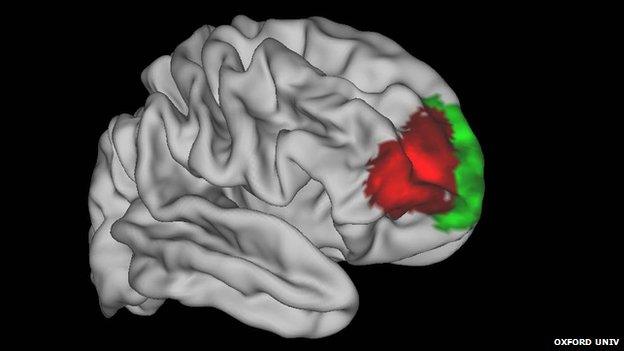

MRI scan of the human prefontal cortex. The green section resembles an area found in monkeys but the red area may be unique to humans

This was my second visit to the Biomedical Sciences building, and I'm the only journalist to have ever been allowed inside.

The University wants to publicise the research here but is wary of visitors, given the history of the building.

Concordat

In 2004 construction stopped after a campaign of intimidation by animal rights extremists.

Work re-started more than year later when the government stepped in and took over the costs of security.

Tough new laws and more rigorous policing led to a clampdown on extremists. Several activists were jailed.

Many feel that the climate surrounding animal research is less heated, and more positive than it has been for years.

Oxford University is one of more than 40 organisations involved in UK bioscience which agreed to develop a Concordat on openness on animal research.

This went out for consultation two months ago. The aims include ensuring the public have accurate information about what research involves and the role it plays in scientific discovery.

All animal procedures are controlled by the Home Office. There are strict regulations, with the tightest controls surrounding experiments on primates.

This mouse is part of research into Parkinson's disease

GM mice

Out of four million animal procedures last year in the UK, 3000 were on monkeys. Three quarters of all procedures are on mice.

Oxford has around 50,000 mice, almost all of them genetically modified to enable scientists to investigate single human disorders.

I was shown a cage of mice which - although they looked normal - had genes inserted to mimic Parkinson's disease. Other cages held mice with Alzheimer's or a heart condition.

The third group of animals I met were ferrets. They were being used in experiments on the effects of temporary hearing loss. The ferrets can be fitted with removable earplugs.

Insights into how the brain compensates could point the way to new treatments for glue ear, a common childhood condition.

Transparent

This research is also funded by the Wellcome Trust, one of the world's biggest funders of medical research aimed at benefiting humans and animals.

It's former Director, Sir Mark Walport is now the government's Chief Scientific Advisor. He wants to encourage greater openness by researchers.

"People are becoming more confident and more transparent about animal research and I think that is extremely important.

Ferrets are used in hearing experiments

" It is important to remember that every time you take pretty much any pharmaceutical agent you are benefitting from many years of studies on humans and on animals - and of course that research benefits animals as well."

But Michelle Thew, from the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, said animal experiments were archaic and inhumane.

"I want to see good medicine and cures for diseases but we need progressive modern research.

"We are simply getting very good at curing diseases in animals; we are not good at curing them in people. We should be investing more in alternatives such as cell culture and and computer modelling."

Both sides of the animal research debate say they want the public to be better informed about the issues. The government says it is committed to seeking alternatives to animal research wherever possible.

Although the overall number of animal procedures rose slightly in 2012, this was largely due to an increase in the breeding of genetically modified mice.

The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 enshrines the policy of "three Rs'": replacement, refinement and reduction.

But despite efforts to find alternatives to animals, it seems certain that procedures on the mice, rats, fish, frogs, ferrets, guinea pigs and monkeys in Oxford will continue for many years to come.