Cells from eyes of dead 'may give sight to blind'

- Published

The necessary cells can be found in the back of everyone's eyes

Cells taken from the donated eyes of dead people may be able to give sight to the blind, researchers suggest.

Tests in rats, reported in Stem Cells Translational Medicine, external, showed the human cells could restore some vision to completely blind rats.

The team at University College London said similar results in humans would improve quality of life, but would not give enough vision to read.

Human trials should begin within three years.

Donated corneas are already used to improve some people's sight, but the team at the Institute for Ophthalmology, at UCL, extracted a special kind of cell from the back of the eye.

These Muller glia cells are a type of adult stem cell capable of transforming into the specialised cells in the back of the eye and may be useful for treating a wide range of sight disorders.

In the laboratory, these cells were chemically charmed into becoming rod cells which detect light in the retina.

Injecting the rods into the backs of the eyes of completely blind rats partially restored their vision.

Brain scans showed that 50% of the electrical signals between the eye and the brain were recovered by the treatment.

One of the researchers, Prof Astrid Limb, told the BBC what such a change would mean in people: "They probably wouldn't be able to read, but they could move around and detect a table in a room.

"They would be able to identify a kettle and cup to make a cup of tea. Their quality of life would be so much better, even if they could not read or watch TV."

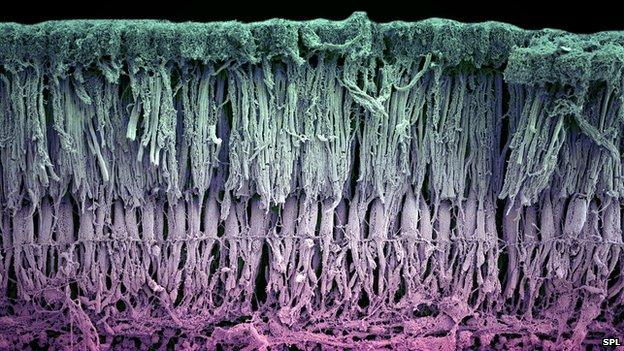

The different layers of the retina, with the light-sensing rods and cones at the top

The cells might be able to help patients with disorders such as macular degeneration or retinitis pigmentosa.

Human stem cell trials are already taking place using material taken from embryos.

However, this is ethically charged and takes several months to prepare the cells. The Muller glia cells can be ready within a week.

Prof Limb commented: "They are more easily sourceable and very easy to handle in the lab so from that perspective they're better, but they do express antigens that could induce an immune response."

It means the donated cells could be rejected like an organ transplant.

The next step is to prepare the cells as a clinical grade treatment in order for human trials to begin.

The researchers believe it could take three years before such a trial takes place.

Dr Paul Colville-Nash, the regenerative medicine programme manager at the Medical Research Council, which funded the study, said: "This interesting study shows that Muller glial cells are another viable avenue of exploration for cell therapy in retinal diseases.

"It's not clear yet which approach will be most effective when these experimental techniques enter human trials, which is why it is important to progress research across all avenues in pursuit of a cure for sight loss."

- Published7 March 2012

- Published24 January 2012

- Published29 January 2014

- Published22 July 2013