Can Britain end its love affair with sugar?

- Published

- comments

Where is sugar found in the diet and what does it do to your body?

Ask someone how much sugar they consume and the chances are they would vastly underestimate the amount.

Research has shown that the average Briton packs away 238 teaspoons a week - that is nearly 1kg.

The reason? So much is hidden, says Dr Gail Rees, a nutrition expert from Plymouth University.

"It's not just in the obvious culprits, such as fizzy drinks and confectionery.

"Sugar is lurking in any number of seemingly innocuous everyday foodstuffs, such as canned tomatoes, salad dressings, peanut butter, breakfast cereals, bread, pasta - the list goes on."

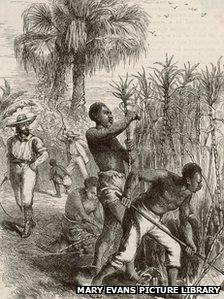

Slaves from West Africa were forced to work on sugar plantations

Of course, it wasn't always like this.

Prior to the 1600s, it was the preserve of the rich.

Instead, honey was the main way of sweetening food.

That began to change in the 1600s when settlers on Barbados discovered sugar cane thrived in the island's stony soil.

And so began the "sugar rush" as slaves were transported form West Africa to work on the plantations.

Bete noire

By the early 1800s Britons were consuming over 5kg per year on average.

But after the Gladstone government decided to lift the tax on sugar in the 1870s, consumption jumped again topping 20kg by the time Queen Victoria's reign came to an end.

Now experts want us to curb the amount we eat amid suggestions it is addictive and a major cause of obesity.

This week the World Health Organization has called for sugar consumption to be halved, while England's chief medical officer Dame Sally Davies has suggested a sugar tax should be reinstated.

No doubt cutting back will prove difficult for many - Britain is known as a nation with a sweet-tooth.

But it begs the question: why such a flurry of activity now after 400 years of enjoying the white stuff?

It is partly a response to research which has started to suggest sugar is both addictive and a more potent harm to health than other sources of calories.

But it is also related to the fact that the argument to reduce salt consumption - the other bete noire of nutritionists - has been won. Intake is estimated to have fallen by 15% over the last 10 years.

A leading voice in that movement was Professor Graham MacGregor, an expert in cardiovascular medicine at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine.

He has just set up a new campaign, Action on Sugar, with the aim of reducing "hidden sugars" by 20% to 30% over the next three to five years.

"It's time we took added sugar out of foods and soft drinks," he says.

The war on sugar has begun.