Beth Warren waits on sperm legal fight result

- Published

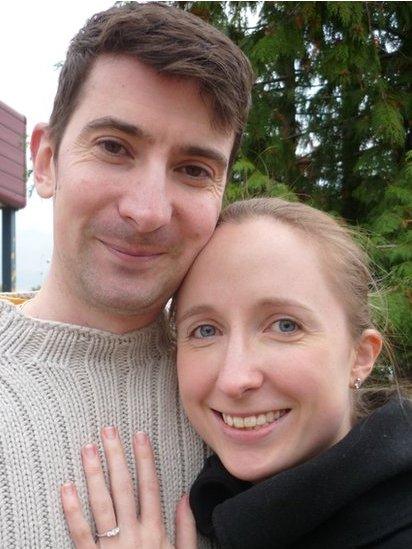

Beth Warren and Warren Brewer were together for eight years

The High Court will rule later on a widow's attempt to prevent her dead husband's sperm from being destroyed.

Beth Warren's husband died from a brain tumour two years ago and she has been told that his sperm cannot be stored beyond April 2015.

The Birmingham woman's lawyers say the regulations defy common sense.

Warren Brewer, 32, had his sperm frozen before having radiotherapy treatment for cancer and signed forms saying his wife could use it if he died.

Regulations state sperm and eggs can be stored for decades, but individuals must update their consent every few years.

That is no longer possible since Mr Brewer's death - so, under current rules, if the sperm is not used within 14 months it will be destroyed.

The couple had been together for eight years and married in December 2011, six weeks before Mr Brewer died.

Mrs Warren, who uses her late husband's first name as her surname, said she was not yet ready to have his child and may never decide to.

But the 28-year-old physiotherapist wants to be able to keep her options open.

She told BBC Radio 5 live: "I can't make that decision, and certainly can't start doing it, at a time when I'm still grieving and professionally trying to establish myself financially and so on."

She said her husband had signed "every form he was given", including one a month before he died, and that the couple had not realised there could be a time limit on how long the sperm was stored.

"We thought we'd done everything that we possibly could," said Mrs Warren.

She said any child she had using the sperm would be brought up surrounded by photographs and videos of her late husband and would have "two families" in their life.

"Of course it's not ideal," she added. "That's something I've got to go over in my head at a time when I'm not so emotional and not still grieving so painfully over my husband."

Mrs Warren told the BBC that if she failed in her current court challenge, her options were to try to get pregnant straight away, ask to have the sperm exported and stored abroad or undergo IVF treatment.

Any embryos created using IVF could be stored until 2018, she said.

The fertility regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, says it has no discretion to extend the storage period.

The case reopens a long-standing debate about the ethics of posthumous conception.

In 1997 the courts ruled Diane Blood should be allowed to take her dead husband's sperm abroad.

In that case there was never any written consent.

Ms Blood went on to have two sons.

- Published4 December 2013