Living organ regeneration 'first' by gene manipulation

- Published

An elderly organ in a living animal has been regenerated into a youthful state for the first time, UK researchers say.

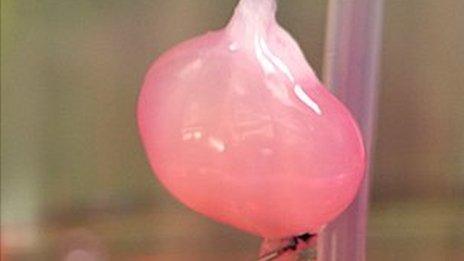

The thymus, which is critical for immune function, becomes smaller and less effective with age, making people more susceptible to infection.

A team at the University of Edinburgh managed to rejuvenate the organ in mice by manipulating DNA.

Experts said the study was likely to have "broad implications" for regenerative medicine.

The thymus, which sits near the heart, produces T-cells to fight off infection.

However, by the age of 70 the thymus is just a tenth of the size in adolescents.

"This has a lot of impacts later in life, when the functionality of the immune system decreases with age and you become more vulnerable to infection and less responsive to vaccines," one of the researchers, Dr Nick Bredenkamp, told the BBC.

Boosting

The team at the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh tried to regenerate the thymus of old mice.

A gene, called Foxn1, naturally gets shut down as the thymus ages. So they tried to boost it back to youthful levels.

A drug was used to increase the activity of the gene in elderly mice.

The results, published in the journal Development, showed that boosting Foxn1 activity in elderly mice could give them the thymus of a much younger animal.

Dr Bredenkamp said: "We could regenerate the thymus using this method. It increases in size and makes more T-cells. It is almost completely regenerated.

"The exciting thing really is the manner in which it is done. We've targeted a single gene and we've been able to regenerate an entire organ."

More youthful

It is not certain why the thymus shrinks with age. One theory is that it needs a lot of energy to run, which the body starts to divert towards reproduction during adolescence.

Dr Bredenkamp argued that the technique could eventually be adapted to work in people, but it would need to be "very tightly controlled" to ensure the immune system did not then go into overdrive and attack the body.

It also raises the prospect that other organs in the body, such as the brain or heart, could be made more youthful by targeting a single gene.

Dr Rob Buckle, the head of regenerative medicine at the Medical Research Council, said: "One of the key goals in regenerative medicine is harnessing the body's own repair mechanisms and manipulating these in a controlled way to treat disease.

"This interesting study suggests that organ regeneration in a mammal can be directed by manipulation of a single protein, which is likely to have broad implications for other areas of regenerative biology."

- Published15 April 2013

- Published3 July 2013