Why big buttocks can be bad for your health

- Published

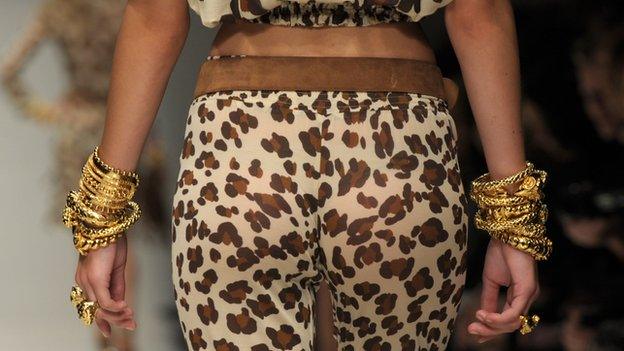

Many Venezuelan women go to dangerous lengths in pursuit of their ideal figure

The demand for bigger buttocks in Venezuela means some women will even have banned injections to achieve them, putting their health at risk.

It is with tears in her eyes that Denny recounts how she woke up one day to find a bump the size of a football in her lower back.

She could not walk or bend down, and the pain was intense.

Even before she saw a doctor, Denny, a 35-year-old Venezuelan lawyer, knew the bump must be a side-effect of liquid silicone that had been injected in her buttocks.

It had moved into her back and was putting pressure on her spine.

"It was a terrible shock. I couldn't walk. That's how my agony started," she says.

Buttock injections are one of many common cosmetic procedures Venezuelan women undergo to achieve what society deems to be beautiful.

The injections were banned by the government in 2012, six years after Denny had them.

Banned Venezuela buttock silicone injections 'can be lethal'

But the practice continues in spite of the ban. Up to 30% of women between 18 and 50 choose to have these injections, according to the Venezuelan Plastic Surgeons Association.

Men also get injected to boost their pectoral muscles, though the numbers are lower.

No barriers

The injections are made using a biopolymer silicone. The fact that this is injected freely into the body makes it more dangerous than implants, where silicone gel is contained within a shell.

The big attraction is that they are much cheaper than implants. An injection can cost as little as 2000 bolivares (£191, $318) and the whole procedure doesn't take more than 20 minutes.

But the risks are incredibly high.

"The silicone can migrate into other areas of the body, because it doesn't have any barriers. The body can also react immunologically against a foreign material, creating many problems," says Daniel Slobodianik, a cosmetic surgeon.

An MRI scan shows that liquid silicone, injected into her buttocks, has moved to Denny's back

He adds that symptoms can appear years after the procedure.

Patients can suffer from allergic reactions and chronic fatigue. If the liquid migrates to other areas of the body it can cause intense joint pain.

In Denny's case, the silicone moved up into her back, putting painful pressure on her spine and making it difficult to walk.

But to some extent she was lucky.

Figures are unclear, but the Venezuelan Plastic Surgeons Association fear that at least a dozen women die every year from these injections.

Dr Slobodianik is only one of two specialists in the country who operate to remove tissue affected by the injections.

Dr Slobodianik is one of only two specialists in Venezuela who remove tissue affected by the injections

He says he has a long waiting list, and Denny had to wait for a year until she could get the surgery.

Many cannot even afford to be operated, because the surgery alone costs around 60,000 bolivares.

"Perfect measurements"

Hours before the delicate surgery, Denny explains that she prefers to withhold her full name because some of her family members don't know why she got ill.

They think she has a back problem - which is also what she thought for years, before the bump appeared.

She says she would have not taken the same decision if she had been aware of the risks.

Mannequins in Venezuela give an idea of the 'perfect' dimensions that many women aspire to

She describes the peer pressure that pushed her to get injected.

"There was a boom. In the office all the women had such nice buttocks. The last straw was when a judge I work with walked in, looking good. Her buttocks looked like two balloons, they were so beautiful," she says.

"I was never obsessed with perfect measurements, but then I let myself be dragged along by the idea that Venezuelan women should look like Barbie dolls."

Venezuelans have won Miss Universe seven times, giving the country a reputation as a factory of beauty queens.

"Self-esteem"

According to Carolina Vazquez Hernandez, a counsellor specialising in women's issues, societal pressure is huge here - even more so than in other countries.

"We Venezuelan women don't have a clear identity of our roots. Because of this lack of identity, our self-esteem is very weak, and we are able to subject ourselves to anything that will develop our self-esteem," says Ms Vazquez Hernandez.

Astrid de la Rosa agrees. She is one of the leading campaigners of the No to Biopolymers association, a non-profit organisation set up to offer support to victims of silicone injections.

She says she decided to undergo the procedure herself because her partner was about to leave her.

"I thought that a person will love you because of the way you look," she says.

Shortly after, she started feeling sick. Doctors said her immune system had been affected and diagnosed her with leukaemia.

The government ban on biopolymer injections was partly thanks to the work of the No to Biopolymer association.

But Ms de la Rosa says it is not enough.

"Where is the help for us?"

She says she still receives weekly calls from women who get injected, even though it is now illegal.

"It is not a matter or gender or social class. Women and men do it, there are politicians, actors that have done it," she says. "Where is the help for us?"

Dr Slobodianik shows what can happen when buttock injections go wrong

While the government has banned biopolymer injections because of their health risk, insurance companies do not cover any costs for remedial treatment, because they don't recognise the side-effects of the injections as an illness.

Ms de la Rosa says her organisation often collects money to help victims pay for surgery.

Denny managed to finance the surgery with her own savings, but money is not on her mind at the moment.

Lying face down in her bed after the surgery, she knows it will take her three weeks until she has finally recovered, and the scar will remain forever.

She is also aware that the silicone may still affect her in the future.

However, she hopes that her tragic experience can at least serve as a warning for women considering having the injections - and help them learn to accept their bodies for what they are.