Anatomy of female genital mutilation

- Published

The world could put a stop to female genital mutilation (FGM) within a generation, international leaders and campaigners say. (This report contains graphic descriptions of the practices involved).

The ambitious pledge to end FGM comes from a UK summit, external dedicated to the topic, hosted by Prime Minister David Cameron.

So what is FGM, and why is it still being carried out on millions of women and girls around the world?

'Cutting'

Female genital mutilation (FGM) includes any procedure that alters or injures the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

In its most severe form, after removing the sensitive clitoris, the genitals are cut and stitched closed so that the woman cannot have or enjoy sex.

A tiny piece of wood or reed is inserted to leave a small opening for the necessary flow of urine, and monthly blood when she comes of age (most FGM is carried out on infants or young girls before they reach puberty).

When she is ready to have sex and a baby, she is "unstitched" - and then sewn back up again after to keep her what is described by proponents as "hygienic, chaste and faithful".

In societies where FGM is commonplace, a woman can bring shame on herself and her family if she does not comply. Some see it as a religious necessity - though no scriptures explicitly prescribe it.

Types of FGM

•Clitoridectomy - partial or total removal of the clitoris

•Excision - removal of the clitoris and inner labia (lips), with or without the outer labia

•Infibulation - cutting, removing and sewing up the genitalia

•Any other type of intentional damage to the female genitalia (burning, scraping et cetera)

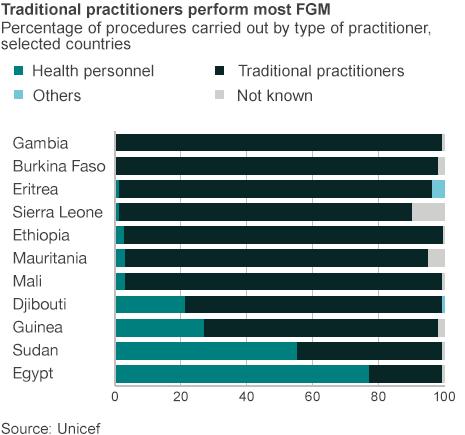

Most often, the procedure is carried out by traditional circumcisers or preachers, using crude, accessible tools, such as thorns and thread, broken glass or razor blades, and without anaesthetic.

The pain is part of the centuries-old ritual - to prove that the woman is strong and can endure it. Corrosive substances may also be inserted into the vagina to scar, tighten and narrow it.

But about a fifth of all FGM is now performed by healthcare workers in hospital settings - bespoke clinics that use scalpels and antiseptics - and the trend towards medicalisation is increasing, says the World Health Organization.

Medicalisation

This is partly to counter the argument that FGM is unsafe, external. A big risk with FGM is dangerous bleeding and infection. By doing it in a clinic, these risks can be minimised.

Another compelling reason is money. Doctors and midwives in poor countries can boost their salary by selling their services.

Efua Dorkenoo, senior FGM advisor at Equality Now, who has been campaigning for decades to put an end to FGM, said: "In Egypt, around 70% of FGM is done by medical doctors. In Kenya and Nigeria, local midwives are cutting.

"The medical professionals, they think that if it can't be stopped it's best to do it in the medical setting. And some are doing it for money."

And it's not just something that's done outside of the West. There have been numerous reports of the practice documented in the UK, even though it is illegal.

While it is hard to get a handle on the true scale, figures suggest at least 4,000 women and girls have been treated for FGM in London's hospitals since 2009.

As yet, there have been no convictions for these crimes. And it's something that's been going on quietly for decades, says Ms Dorkenoo.

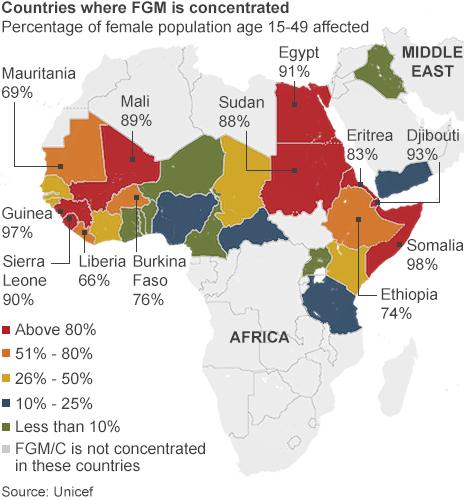

Unicef estimates that more than 130 million girls and women alive in the world today have undergone FGM, mostly for cultural, religious and social reasons, although support for FGM is falling.

There are no health benefits, but many risks associated with FGM even when it is done in a hygienic setting.

An obvious one is severe pain - both physical and psychological.

Victims recall fighting to get free as they were held down and their legs forcibly spread for the cutting.

Isa, who was cut when she was six, recalls: "I can still remember the shouting. I can still remember the blood coming through. I can still remember the pain."

She's since had surgery and, as a trained midwife, helps other women who have undergone FGM.

Surgery may reverse some of the damage, but it cannot restore sensitive tissue that has been removed.

Nor can it repair emotional scars.

Janet Fyle, who is the Royal College of Midwives' lead advisor on FGM, says: "Some women have flashbacks similar to soldiers who have been in battle.

FGM is shrouded in secrecy and some women are too fearful to speak out

"If they were kidnapped on their way to collect water or someone held them down, its a trauma to them psychologically and its very difficult to deal with those scars."

She hopes that FGM will become a thing of the past.

"I have hopes that we will end it in a generation. At least here in the UK.

"The younger girls are more aware of it. We need to educate and empower them."

But she says FGM is deeply embedded in many cultures - and that could take a long time to change.

Efua Dorkenoo agrees: "In the most bizarre way, women have become the perpetrators and practisers of this and keep the tradition going. If you speak to women, they may say they want it because it's linked to them being accepted by society. It's at the core of controlling a woman's sexuality.

"Because it's to do with sexuality, it's still very taboo to talk about."

Asetta's story

.jpg)

Mother-of-three Asseta was cut when she was seven years old. In Burkina Faso, where Asseta lives, more than 75% of girls and women have been cut.

Asseta says: "I was told there were some eggs to eat - so me and my friends rushed over. But when we got there, there was blood all over the floor from other girls. It was very difficult - being cut is an event I will never forget.

"Deciding not to get my daughters cut was a tough decision to make.

"Going against tradition can be difficult. First you need to convince yourself that the decision you're making is the best one - you need to know the facts in order to do that.

"I hope my daughter will have a better life, better health because of my decision. And I hope she will do the same for her daughters and avoid cutting."

Asseta's daughter, 13-year-old Fatmata, says: "I had heard about FGM and I've seen it happen - a friend of mine was cut when she was 12 years old. Seeing it happen made me feel scared. I don't want to be cut, and I'm happy knowing my parents aren't going to make me do it."

In many places where FGM is done, there is no law against it, or if there is, it's not implemented. And politicians have been afraid to push too far, says Efua Dorkenoo, who has herself received death threats for speaking out against FGM.

There was a UN resolution in 2012 to ban FGM worldwide.

"Now is the time for the international community to make this happen," says Ms Dorkenoo.

- Published15 April 2014

- Published3 July 2014

- Published19 March 2014

- Published30 May 2014

- Published17 March 2014

- Published25 July 2013