MPs call for newborn muscular dystrophy test

- Published

Duchenne muscular dystrophy affects one in 3,500 newborn boys in the UK

A group of MPs is urging the government to allow the testing of newborn boys for a deadly muscle wasting disease.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) affects one in every 3,500 newborn boys, and many will die before age 30.

Although a test exists, it is not used to check for the disorder at birth in the UK.

Opponents say the test is too unreliable and that with no effective treatment on offer, screening is inappropriate.

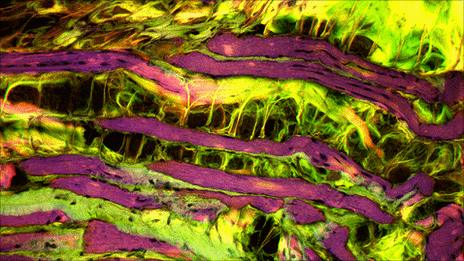

Duchenne muscular dystrophy can become fatal when it affects the muscles needed to breathe and pump blood around the body.

Those with the condition can need a wheelchair by the age of 10.

Testing before a cure?

The current average age of diagnosis for the disease was five years old, said the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign, by when a child would have lost 30-40% of their muscle mass.

Doctors currently rely on family history, external, symptoms, blood, nerve and muscle tests, and muscle biopsies to diagnose the condition.

But it can be detected with a simple blood test, in some instances at birth.

An inquiry into testing for the condition has been led by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Muscular Dystrophy. While the MPs agree that the DMD test needs perfecting, they say current screening rules are too prohibitive and prevent newborn screening for the disease.

The group said the criteria governing testing for DMD stated symptoms should be present at birth in order for any newborn screening test to be considered.

But it said it "may always be particularly hard" for the disorder to meet this, as symptoms often appeared later in childhood.

The criteria also stated there "should be an effective treatment for patients identified through early detection", but the group said families whose children had DMD said they would want a test even without a treatment.

The report said families would rather know so they could prepare, by finding schools, changing their housing, and arranging treatment.

MPs said the first treatments for the disorder were in the final stages of trials and called for the rules to be reconsidered. A treatment could be available in the US as early as 2015.

A test could be available in five years, said the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign.

Not knowing

The Muscular Dystrophy Campaign said there was a risk that without early testing, parents would not know if they were a carrier for the gene linked to DMD and so could go on to have several more children with DMD.

A newborn DMD blood test available in Wales from 1990 to 2011 had been withdrawn due to inaccuracies, and in 2012 the UK National Screening Committee had decided not to introduce it across the UK, said the report.

Jane Field's son, Murray, 16, has DMD. She told the BBC he had been seven by the time the family had realised he had the disorder after three and a half years of misdiagnoses.

She said: "I can only say from my point of view that the absolute horror, when you know something is wrong but you don't know what it is, is absolutely devastating."

Ms Field said there "absolutely" should be a test even if there was a risk of false positives.

Lacking treatment

"There is never a good time to get this diagnosis. To put it bluntly the screening committee should be supporting work on a more accurate Duchenne test for newborns. It is already being done in the US," she added.

Dr Anne Mackie, director of programmes at the UK National Screening Committee, told the BBC misdiagnosis had been an issue when the test was run in Wales.

She said: "My duty is to make sure if we do recommend a test to parents, that it is a really good one. But that also we are able to say to parents of a positive test, 'This is what we can do for you and it will make a difference.'"

Dr Mackie said one of the "major problems" was the treatments were "not as good" as the committee would "wish them to be".

She added: "I know the APPG is pushing for improvements in tests and there are some exciting developments, but for the moment, we can't say hand on heart if your baby has this test, this will happen and we can help."

- Published6 May 2013

- Published24 January 2012

- Published25 July 2011