Multiple sclerosis discovery may explain gender gap

- Published

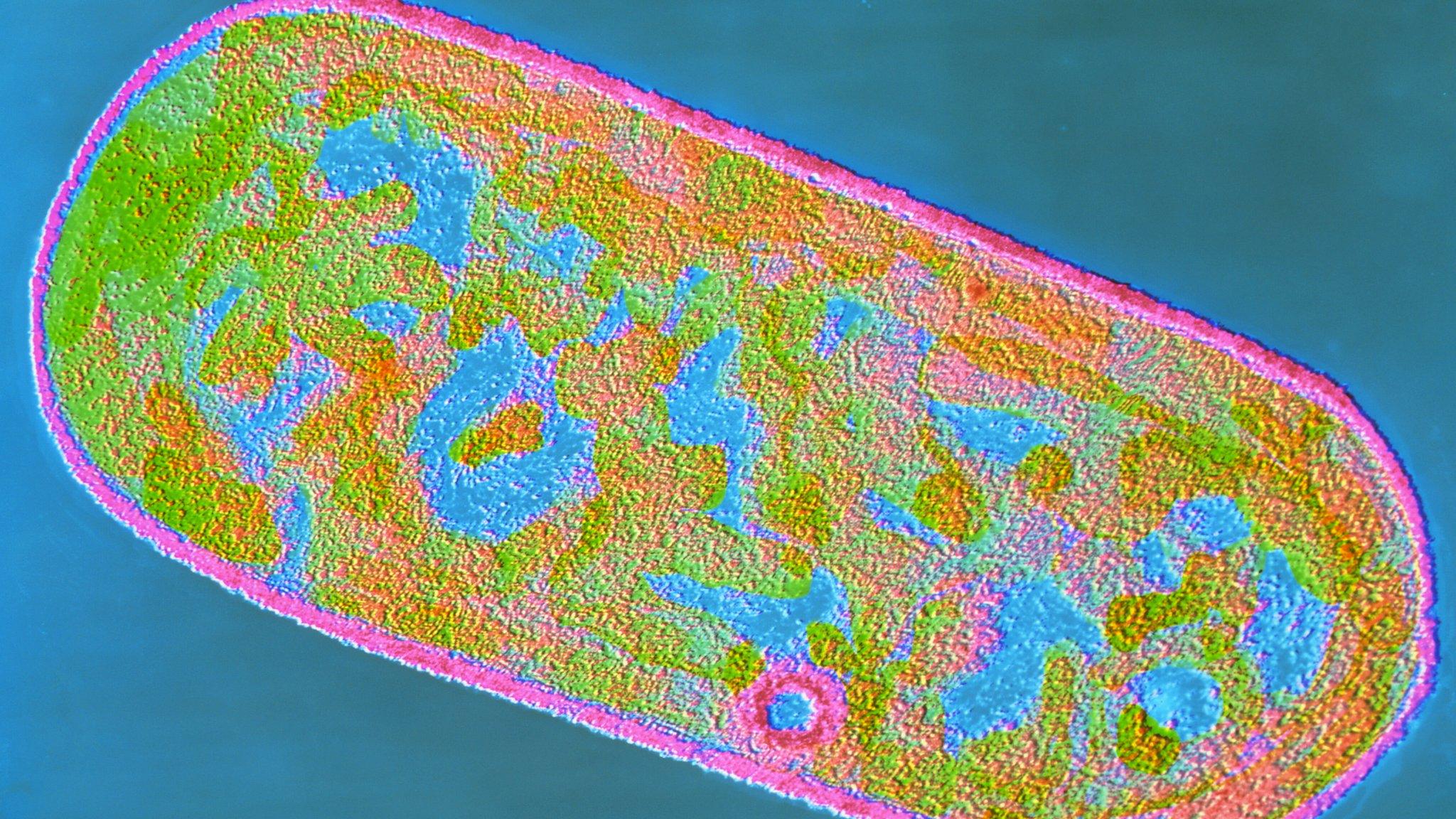

Scientists said the S1PR2 protein was linked to multiple sclerosis

A key difference in the brains of male and female MS patients may explain why more women than men get the disease, a study suggests.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in the US found higher levels of protein S1PR2 in tests on the brains of female mice and dead women with MS than in male equivalents.

Four times more women than men are currently diagnosed with MS.

Experts said the finding was "really interesting".

MS affects the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, which causes problems with muscle movement, balance and vision. It is a major cause of disability, and affects about 100,000 people in the UK.

Blood-brain barrier

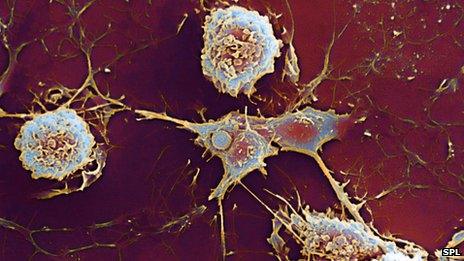

Abnormal immune cells attack nerve cells in the central nervous system in MS patients.

There is currently no cure, although there are treatments that can help in the early stages of the disease.

Researchers in Missouri, external looked at relapsing remitting MS, external, where people have distinct attacks of symptoms that then fade away either partially or completely. About 85% of people with MS are diagnosed with this type.

Scientists studied the blood vessels and brains of healthy mice, mice with MS, and mice without the gene for S1PR2, a blood vessel receptor protein, to see how it affected MS severity.

They also looked at the brain tissue samples of 20 people after they had died.

They found high levels of S1PR2 in the areas of the brain typically damaged by MS in both mice and people.

The activity of the gene coding for S1PR2 was positively correlated with the severity of the disease in mice, the study said.

Scientists said S1PR2 could work by helping to make the blood-brain barrier, in charge of stopping potentially harmful substances from entering the brain and spinal fluid, more permeable.

A more permeable barrier could let attacking cells, which cause MS, into the central nervous system, the study said.

Understanding 'crucial'

Prof Robyn Klein, of the Washington University School of Medicine, said: "We were very excited to find the molecule, as we wanted to find a target for treatment that didn't involve targeting the immune cells.

"This link [between MS and S1PR2] is completely new - it has never been found before."

Prof Klein said she did not know why the levels of S1PR2 were higher in women with MS, adding she had found oestrogen had "no acute role".

She would be looking at taking her findings to clinical trials in the "next few years", she added.

Dr Emma Gray, of the MS Society, said: "We don't yet fully understand why MS affects more women than men, and it's an area that's intrigued scientists, and people with MS, for many years.

"A number of theories have been suggested in the past, including the influence of hormones or possible genetic factors - and this study explores one such genetic factor in further detail, which is really interesting."

She said understanding the causes of MS was a "priority" for the MS Society in the UK, and could be "crucial" in finding new treatments.

The research was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

- Published19 March 2014

- Published29 January 2014