What Leonardo taught us about the heart

- Published

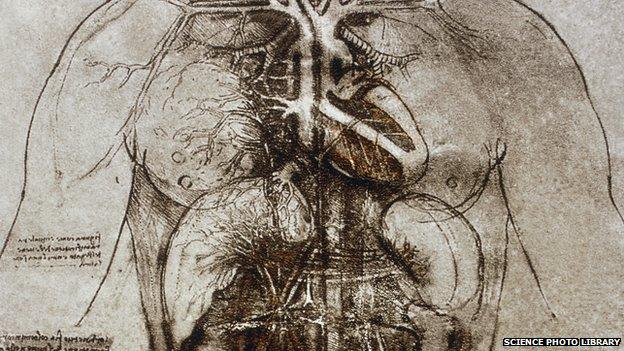

Leonardo da Vinci was drawn to the inner workings of humans, animals and plants. This is his drawing of the female anatomy, including the heart and major organs

When Leonardo da Vinci dissected the heart of a 100-year-old man who had recently died, he produced the first known description of coronary artery disease.

More than 500 years later, coronary artery disease is one of the most common causes of death in the western world.

The Italian painter, architect and engineer was clearly a curious and gifted individual who was way ahead of his time, but what fired his interest in the workings of the human body?

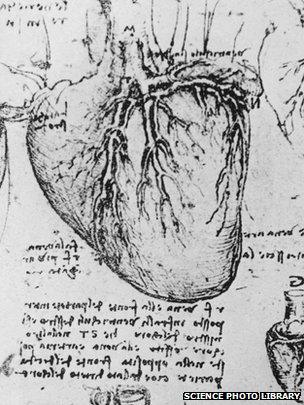

A Leonardo diagram showing the heart and its blood vessels, with his mirror writing annotating it

"He had a great mind, and he was willing to really look and see," says Mr Francis Wells, a consultant cardiothoracic surgeon at Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, who has spent years studying Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical drawings, which form part of the Royal Collection, external in Windsor.

Leonardo's investigations of the human form were a lifelong interest.

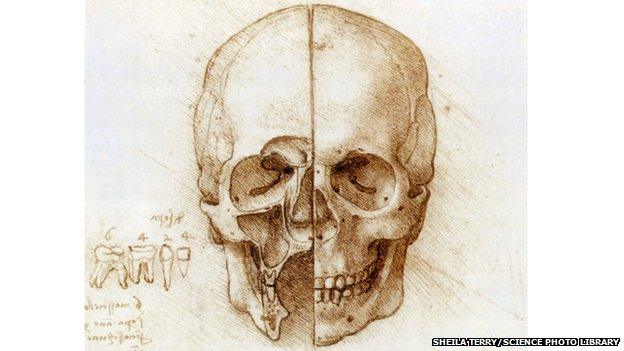

His diagrams and sketches of the skull, skeleton, muscles and major organs fill countless notebooks while his theories on how they function fill many more pages.

But it was the heart that appeared to particularly fire his interest, from 1507 onwards, when he had reached his 50s.

In those drawings, he used his knowledge of fluids, weights, levers and engineering to try to understand how the heart functions.

He also looked closely at the actions of the heart valves and the flow of blood through them.

Mr Wells' book, 'The Heart of Leonardo', explores the artist's drawings and writings on the organ, and he says his insights are "quite astonishing".

"The more we look, the more right we realise he was," he adds.

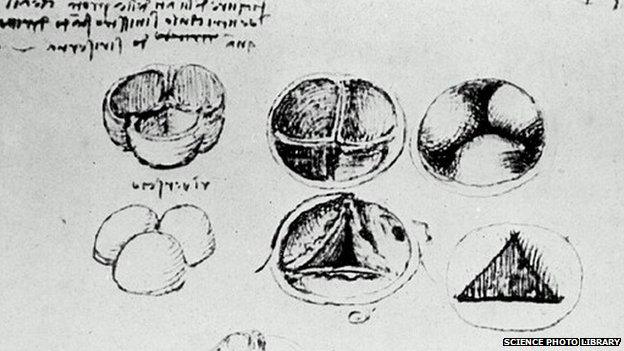

Leonardo used warm wax to make a cast of the heart valves' form in their natural state

Many of Leonardo's conclusions, such as the description of how the arterial valves close and open - letting blood flow around the heart - holds true today, but is not widely known.

"Even cardiologists get this wrong now," Mr Wells says.

"Only with the use of MRI technology has knowledge of this subject been revisited."

Many of Leonardo's drawings were based on studies of hearts from ox and pigs. It was only later in life that he had access to human organs, and these dissections had to be carried out quickly in winter before the body began to degrade.

Contemporary dissections of the heart show he was correct on many aspects of its functioning.

For example, he showed that the heart is a muscle and that it does not warm the blood.

Da Vinci was the first anatomist known to correctly note the number and root structure of human teeth

He found that the heart had four chambers and it connected the pulse in the wrist with the contraction of the left ventricle.

He worked out that currents in the blood flow, created in the main aorta artery, help heart valves to close.

And he suggested that arteries create a health risk if they fur up over a lifetime.

Mr Wells also believes that Leonardo realised that the blood was in a circulation system and may have influenced William Harvey's discovery in 1616 that blood was pumped around the body by the heart.

Yet none of Leonardo's theories or drawing were ever published during his lifetime.

In fact, his notes were not rediscovered until the late 18th century - more than 250 years after his death.

Mr Wells explains: "It wasn't his job. Scientific stuff was his hobby."

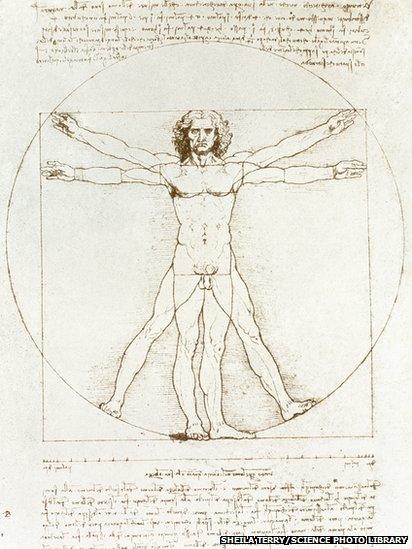

His study of man's movements, perhaps one of his most famous drawings

Being an artist, architect and engineer was the day job and, as a result, his discoveries stayed hidden.

With hindsight they may have had the potential to revolutionise surgery.

In the 16th century, for example, there was no treatment for cardiac disease, or many other diseases, and surgeons occupied a low status in society.

If people survived surgery, it was more by luck than judgement.

Heart surgery has of course transformed in the past century, but Leonardo's insights could have made a huge difference if they had been made public earlier.

Even now, however, there is common consensus that we have barely scratched the surface of what we know about the heart.

According to Mr Wells, Leonardo's legacy is that we should follow the Renaissance Man's example and continue to challenge, question and enquire rather than listen to accepted wisdom.

Who was Leonardo da Vinci?

Leonardo da Vinci was born in Tuscany, Italy, in 1452 - the illegitimate son of a farmer's daughter.

He is known as one of the greatest artists who ever lived. His most famous works of art are The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa.

But there was much more to Leonardo than his paintings.

Despite little formal education, he kept extensive notebooks filled with his scientific theories, inventions, drawings and designs.

Leonardo wrote backwards, from right to left; his writing can be read normally if viewed in a mirror.

More than 4,000 pages have been found, but many are thought to have been lost.