Ebola: The race for drugs and vaccines

- Published

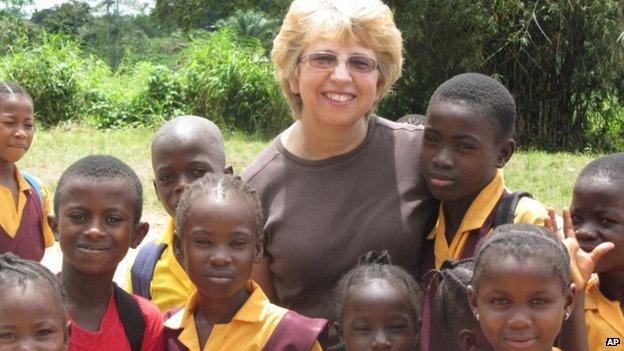

Many organisations are working together to find suitable medicines

The race is on to find ways to prevent and cure the Ebola virus - a disease that has killed more than 10,000 people in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

There are no proven treatments for Ebola or vaccines to prevent individuals becoming infected.

However, progress is now being made on an unprecedented scale.

Trials, which would normally take years and decades, are being fast-tracked on a timescale of weeks and months.

Vaccines in development

The aim is to use the lowest dose of vaccine possible that provides protection

Vaccines train the immune systems of healthy people to fight off any future infection.

Three potential immunisations are frontrunners, having been rushed from promising animal studies into human trials.

One is produced by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and the National Institutes of Health in the US, another is being developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in collaboration with Merck.

And the third to enter human testing is made by Johnson and Johnson together with the company Bavarian Nordic.

The plan is for the different vaccines to be tested in several separate trials across the three worst affected countries in the next few months.

GSK's version uses a chimpanzee common cold virus to carry a single Ebola protein. The vaccine cannot trigger either disease but the hope is it will prompt the production of protective antibodies against Ebola.

Trials in Liberia started in February 2015.

They have three separate parts. Scientists hope to recruit 10,000 people to be given the GSK vaccine, 10,000 to receive the Merck jab and a further 10,000 to get a dummy, placebo vaccine.

So far the GSK and Merck vaccines have been deemed safe in some 600 volunteers. Further testing is underway to see whether the immunizations actually offer protection against the disease.

The jabs are being tested in unaffected countries first

The Merck vaccine used in the Liberian trial is based on a livestock virus, carrying a single Ebola gene.

It is also being trialled in a separate study in Guinea. Here it is being given to anyone who has recently come into contacted with an infected person.

Johnson and Johnson announced the start of their vaccine trial at the beginning of 2015. This uses a different approach still - two separate jabs will be given in the hope the second one boosts the effectiveness of the first.

Vaccine company Novavax has recently announced the start of an Australian trial designed to investigate another potential immunization on healthy human volunteers.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is also evaluating developments in Russia and Japan.

Vaccine challenges

Some experts now say, with Ebola cases going down in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, it will be harder still to prove whether a vaccine actually works.

And researchers will have rely on thousands of volunteers to test these as yet experimental jabs. In some communities, they will face mistrust.

There are also practical issues to take into account - some of the immunisations need to be kept at minus 80C in hot countries with limited access to electricity.

But if all these obstacles are overcome and a vaccine is found to work, there is hope a jab could be more widely available towards the end of 2015.

Questions will then be asked about who gets the vaccine first.

Promising drugs

Several experimental treatments are under development

Drug research is also taking place at pace. Instead of preventing infection like vaccines, these are designed to boost the recovery of those who have been infected.

The WHO says it is getting daily proposals for potential medicine, yet many show no activity against the virus.

Two potential drugs have undergone tests at Medicins Sans Frontieres facilities, external.

Favipiravir - is an antiviral drug approved in Japan for treatment of the influenza virus. It is being tested in Gueckedou, Guinea.

The research is being led by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm).

Early results suggest it might help people who are in the early stages of the illness, but is less likely to be useful in severe cases.

MSF says the trial so far suggests the most vulnerable patients who are most likely to die from the disease don't benefit from favipiravir. The charity says more research is needed and it is to use the drug outside a trial environment.

Brincidofovir - this is an antiviral drug that has been tested in Liberia. This trial was recently stopped as Ebola cases fell.

Other drugs such as ZMapp, external have attracted attention during the outbreak.

Two US aid workers and a Briton recovered after taking ZMapp, but a Liberian doctor and a Spanish priest died.

Like all other drugs, there is a lack of clinical evidence about whether it does work and stocks have been extremely limited so trials have been hampered.

Ethical quandary

Drugs trials are even more ethically controversial than vaccine trials in the midst of this outbreak.

Should normal randomised clinical trials take place?

It allows doctors to know for certain whether a drug is effective, but it means withholding a potentially life-saving treatment during a deadly outbreak.

One option being used is to compare survival in the same centres before and after drugs were used.

Survivors' blood

Blood is screened for diseases before it is transfused

A different approach is to harness one survivor's immune system to help another who is sick.

The body produces Ebola-fighting antibodies in response to the virus.

So the idea is to purify the blood, extract the antibodies and give those to sick patients.

Studies on the 1995 outbreak, external of Ebola in Democratic Republic of Congo showed seven out of eight people survived after being given the therapy.

This approach is being trialled in Guinea, led by the Antwerp Institute of Tropical Medicine.

- Published7 January 2015

- Published5 August 2014