Tiny pieces of gold 'boost brain cancer therapy' in lab

- Published

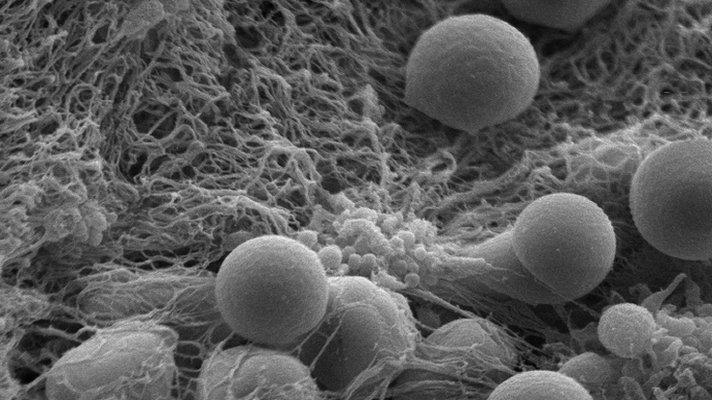

Extremely small pieces of gold can be smuggled into cancer cells

Minuscule pieces of gold may help improve treatment for aggressive brain cancers, according to research published in the journal Nanoscale.

Scientists engineered extremely small golden spheres, coating them with a chemotherapy drug.

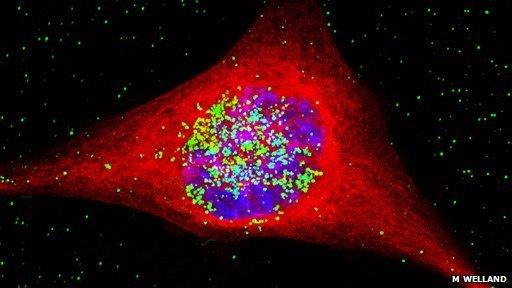

When the tiny particles were infused into the centre of tumour cells, the cancer stopped replicating and many diseased cells died.

Researchers hope it may provide a way to target difficult-to-treat cancers.

'Golden core'

Glioblastoma multiforme is a common form of brain cancer that affects more than 4,000 adults in the UK each year.

Though treatments exist, they have limited effectiveness. Most people with these tumours die within five years of diagnosis.

Researchers created nanospheres - particles that were four million times smaller than a cross-section of a single human hair.

At their core were tiny pieces of gold, surrounded by layers of cisplatin - a commonly used chemotherapy drug.

In trials on samples from human cancers, the spheres appeared to boost the effectiveness of conventional radiotherapy and chemotherapy, improving the chances that all the tumour cells were killed.

Scientists tested the nanospheres on brain-tumour samples extracted during surgery.

The cancer cells were then given a dose of radiotherapy, mirroring currently available treatment.

The radiotherapy not only attacked the tumour cells, it also excited electrons within the golden core. The excited electrons triggered the breakdown of genetic material (DNA) within the cancer.

This process also led to the release of the surrounding chemotherapy, allowing the cisplatin to work on the now weakened tumour.

'Challenging tumours'

Twenty days later, there appeared to be no viable cancer cells left in treated samples.

Prof Sir Mark Welland, of St John's College, Cambridge, who worked on the techniques said: "This is a double-whammy effect.

"And by combining this strategy with cancer cell-targeting materials, we should be able to develop therapy for glioblastoma and other challenging cancers in the future."

Dr Colin Watts, a neurosurgeon involved in the study said: "We need to be able to hit cancer cells directly with more than one treatment at the same time.

"This is important because some cancers are more resistant to one type of treatment than another."

They said this was promising but early research that required many more tests before it could be considered a part of standard treatment.

Researchers hope to start trials in humans in 2016 and are working on early experiments involving other types of tumour.

- Published1 July 2014