Ebola: How bad can it get?

- Published

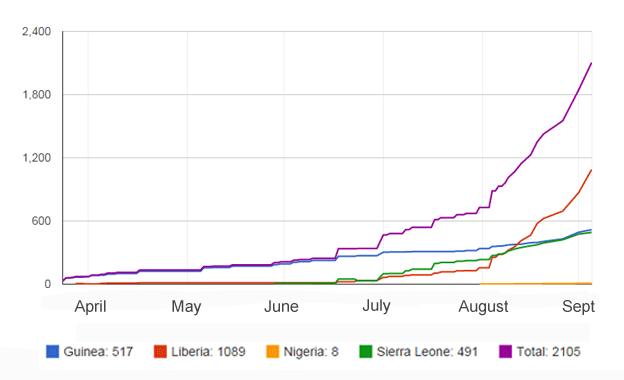

The death toll has passed 2,000 and shows every sign of getting worse

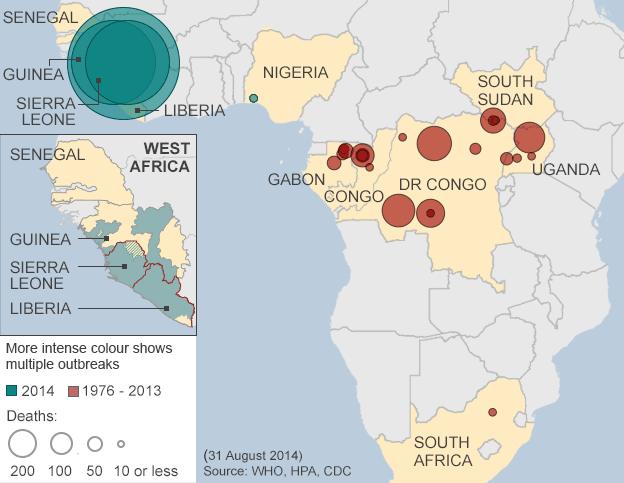

This isn't just the worst single Ebola outbreak in history, it has now killed more than all the others combined.

Healthcare workers are visibly struggling, the response to the outbreak has been damned as "lethally inadequate" and the situation is showing signs of getting considerably worse.

The outbreak has been running all year, but the latest in a stream of worrying statistics shows 40% of all the deaths have been in just the past three weeks.

So what can we expect in the months, and possibly years, to come?

Taking off

Crystal-ball gazing can be a dangerous affair, particularly as this is uncharted territory.

Previous outbreaks have been rapidly contained, affecting just dozens of people; this one has already infected more than 3,900.

But the first clues are in the current data.

Dr Christopher Dye, the director of strategy in the office of the director general at the World Health Organization, has the difficult challenge of predicting what will happen next.

He told the BBC: "We're quite worried, I have to say, about the latest data we've just gathered."

Man outside his home just outside the Liberian capital Monrovia

Up until a couple of weeks ago, the outbreak was raging in Liberia especially close to the epicentre of the outbreak in Lofa County and in the capital Monrovia.

However, the two other countries primarily hit by the outbreak, Sierra Leone and Guinea, had been relatively stable. Numbers of new cases were not falling, but they were not soaring either.

That is no longer true, with a surge in cases everywhere except some parts of rural Sierra Leone in the districts of Kenema and Kailahun.

"In most other areas, cases and deaths appear to be rising. That came as a shock to me," said Dr Dye.

Cumulative deaths - up to 5 September

Only going up

The stories of healthcare workers being stretched beyond breaking point are countless.

A lack of basic protective gear such as gloves has been widely reported.

The charity Medecins Sans Frontieres has an isolation facility with 160 beds in Monrovia. But it says the queues are growing and they need another 800 beds to deal with the number of people who are already sick.

This is not a scenario for containing an epidemic, but fuelling one.

Dr Dye's tentative forecasts are grim: "At the moment we're seeing about 500 new cases each week. Those numbers appear to be increasing.

"I've just projected about five weeks into the future and if current trends persist we would be seeing not hundreds of cases per week, but thousands of cases per week and that is terribly disturbing.

"The situation is bad and we have to prepare for it getting worse."

The World Health Organization is using an educated guess of 20,000 cases before the end, in order to plan the scale of the response.

But the true potential of the outbreak is unknown and the WHO figure has been described to me as optimistic by some scientists.

International spread?

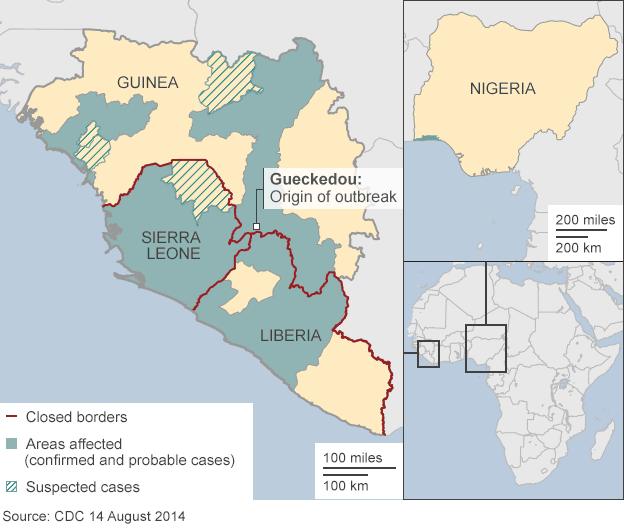

The outbreak started in Gueckedou in Guinea, on the border with Liberia and Sierra Leone.

But it has spread significantly with the WHO reporting that "for the first time since the outbreak began" that the majority of cases in the past week were outside of that epicentre, external with the capital cities becoming major centres of Ebola.

Additionally one person took the infection to Nigeria, where it has since spread in a small cluster and there has been an isolated case in Senegal.

Prof Simon Hay, from the University of Oxford, will publish his scientific analysis of the changing face of Ebola outbreaks in the next week.

He warns that as the total number of cases increases, so does the risk of international spread.

He told me: "I think you're going to have more and more of these individual cases seeding into new areas, continued flows into Senegal, Cote d'Ivoire, and all the countries in between, so I'm not very optimistic at the moment that we're containing this epidemic."

Children watch as another dead body is taken from their village

There is always the risk that one of these cases could arrive in Europe or North America.

However, richer countries have the facilities to prevent an isolated case becoming an uncontrolled outbreak.

The worry is that other African countries with poor resources would not cope and find themselves in a similar situation to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

"Nigeria is the one I look at with great concern. If things started to get out of control in Nigeria I really think that, because of its connectedness and size, that could be quite alarming," said Prof Hay.

End game?

It is also unclear when this outbreak will be over.

Officially the World Health Organization is saying the outbreak can be contained in six to nine months. But that is based on getting the resources to tackle the outbreak, which are currently stretched too thinly to contain Ebola as it stands.

There have been nearly 4,000 cases so far, cases are increasing exponentially and there is a potentially vulnerable population in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea in excess of 20 million.

Ebola deaths

Figures up to 13 January 2016

11,315

Deaths - probable, confirmed and suspected

(Includes one in the US and six in Mali)

-

4,809 Liberia

-

3,955 Sierra Leone

-

2,536 Guinea

-

8 Nigeria

Prof Neil Ferguson, the director of the UK Medical Research Council's centre for outbreak analysis and modelling at Imperial College London, is providing data analysis for the World Health Organization.

He is convinced that the three countries will eventually get on top of the outbreak, but not without help from the rest of the world.

"The authorities are completely overwhelmed. All the trends are the epidemic is increasing, it's still growing exponentially, so there's certainly no reason for optimism.

"It is hard to make a long-term prognosis, but this is certainly something we'll be dealing with in 2015.

"I can well imagine that unless there is a ramp-up of the response on the ground, we'll have flare-ups of cases for several months and possibly years."

It is certainly a timeframe that could see an experimental Ebola vaccine, which began safety testing this week, being used on the front line.

If the early trials are successful then healthcare workers could be vaccinated in November this year.

Here forever

But there are is also a fear being raised by some virologists that Ebola may never be contained.

Prof Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham, describes the situation as "desperate".

His concern is that the virus is being given its first major opportunity to adapt to thrive in people, due to the large number of human-to-human transmissions of the virus during this outbreak of unprecedented scale.

Ebola is thought to come from fruit bats; humans are not its preferred host.

But like HIV and influenza, Ebola's genetic code is a strand of RNA. Think of RNA as the less stable cousin of DNA, which is where we keep our genetic information.

It means Ebola virus has a high rate of mutation and with mutation comes the possibility of adapting.

Prof Ball argues: "It is increasing exponentially and the fatality rate seems to be decreasing, but why?

"Is it better medical care, earlier intervention or is the virus adapting to humans and becoming less pathogenic? As a virologist that's what I think is happening."

There is a relationship between how deadly a virus is and how easily it spreads. Generally speaking if a virus is less likely to kill you, then you are more likely to spread it - although smallpox was a notable exception.

Prof Ball said "it really wouldn't surprise me" if Ebola adapted, the death rate fell to around 5% and the outbreak never really ended.

"It is like HIV, which has been knocking away at human-to-human transmission for hundreds of years before eventually finding the right combo of beneficial mutations to spread through human populations."

Collateral damage

Malaria season is starting in West Africa

It is also easy to focus just on Ebola when the outbreak is having a much wider impact on these countries.

The malaria season, which is generally in September and October in West Africa, is now starting.

This will present a number of issues. Will there be capacity to treat patients with malaria? Will people infected with malaria seek treatment if the nearest hospital is rammed with suspected Ebola cases? How will healthcare workers cope when malaria and Ebola both present with similar symptoms.

And that nervousness about the safety of Ebola-rife hospitals could damage care yet further. Will pregnant women go to hospital to give birth or stay at home where any complications could be more deadly.

The collateral damage from Ebola is unlikely to be assessed until after the outbreak.

No matter where you look there is not much cause for optimism.

The biggest unknown in all of this is when there will be sufficient resources to properly tackle the outbreak.

Prof Neil Ferguson concludes: "This summer has there have been many globally important news stories in Ukraine and the Middle East, but what we see unfolding in West Africa is a catastrophe to the population, killing thousands in the region now and we're seeing a breakdown of the fragile healthcare system.

"So I think it needs to move up the political agenda rather more rapidly than it has."

Ebola virus disease (EVD)

Symptoms include high fever, bleeding and central nervous system damage

Spread by body fluids, such as blood and saliva

Fatality rate can reach 90% - but current outbreak has mortality rate of about 55%

Incubation period is two to 21 days

There is no proven vaccine or cure

Supportive care such as rehydrating patients who have diarrhoea and vomiting can help recovery

Fruit bats, a delicacy for some West Africans, are considered to be virus's natural host