Brain may 'compensate' for Alzheimer's damage

- Published

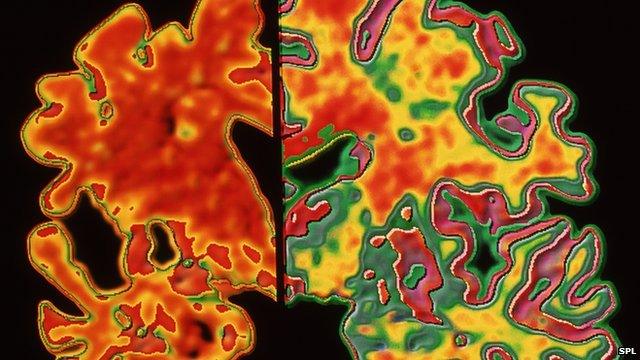

The brains of Alzheimer's patients often have tangles of proteins called amyloid plaques

The human brain may be able to compensate for some of the early changes seen in Alzheimer's disease, research in Nature Neuroscience shows.

The study suggests some people recruit extra nerve power to help maintain their ability to think.

Scientists hope the findings could shed light on why only some people with early signs of the condition go on to develop severe memory decline.

But experts warn much more research is needed to understand these processes.

'Protein tangles'

The study, led by researchers at the University of California, involved 71 adults with no signs of mental decline.

Brain scans showed 16 of the older subjects had amyloid deposits - tangles of protein that are considered a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease.

All participants were asked to memorise a series of pictures in detail while scanners were used to track their brain activity.

They were then asked to recall the gist and later the detail of all the pictures they had seen.

Both groups performed equally well but those with tangles of amyloid in their brains showed more brain activity when remembering the images in detail.

Scientists say this suggests their brains have an ability to adapt to and compensate for any early damage caused by the protein.

Brain stimulation

Dr Laura Phipps, at the charity Alzheimer's Research UK, said: "This small study suggests that our brains may have ways of resisting early damage from these Alzheimer's proteins but more research is needed to know how to interpret these results.

She added: "Longer term studies are needed to confirm whether the extra brain activity seen in this research is a sign of the brain compensating for early damage, and if so, how long the brain might be able to fight this damage."

Scientists say they need to understand why some people with an accumulation of this protein are better at using different parts of their brain than others.

Dr William Jagust, a researcher on the study, said: "I think it is very possible that people who spend a lifetime involved in cognitively stimulating activity have brains that are better able to adapt to potential damage."

- Published8 July 2014

- Published5 April 2013