How not to catch Ebola

- Published

As the outbreak continues to spread, the fear of catching the disease is rising.

Experts are learning more about how to contain the virus that has infected around 7,500 people in West Africa.

The race is on to stop this deadly disease that kills more than half of those it infects.

Here's what is known.

DON'T TOUCH

Ebola is spread by direct contact with contaminated body fluids. Blood, vomit and saliva can all carry and spread the deadly virus.

Medical staff wear rubber gloves that must be regularly disinfected

The relatives of sick patients and the healthcare workers who care for them are at highest risk of infection, but anyone who comes into close proximity potentially puts themselves at risk.

For that reason, contact should only be for essential medical care and always under the full protection of the right clothing.

The virus can't breach protective gear, such as gloves, mask/face shield, a full body suit and tough rubber wellington boots, but too few have access to state-of-the-art kit.

Ebola crisis: How reporters protect themselves while reporting the outbreak

Those who do get to wear it should keep changing it every 40 minutes to be safe. Inside the suit it can get up to about 40C. Getting into the kit takes about five minutes. Taking it off again takes the wearer and a designated helper "buddy" about 15 minutes.

This is one of the most dangerous times for contamination and people are sprayed with chlorine as this happens.

-

Protective Ebola suit

× -

Surgical cap

×The cap forms part of a protective hood covering the head and neck. It offers medical workers an added layer of protection, ensuring that they cannot touch any part of their face whilst in the treatment centre.

-

Goggles

×Goggles, or eye visors, are used to provide cover to the eyes, protecting them from splashes. The goggles are sprayed with an anti-fogging solution before being worn. On October 21, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced stringent new guidelines for healthcare personnel who may be dealing with Ebola patients. In the new guidelines, health workers are advised to use a single use disposable full face shield as goggles may not provide complete skin coverage.

-

Medical mask

×Covers the mouth to protect from sprays of blood or body fluids from patients. When wearing a respirator, the medical worker must tear this outer mask to allow the respirator through.

-

Respirator

×A respirator is worn to protect the wearer from a patient's coughs. According to guidelines from the medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), the respirator should be put on second, right after donning the overalls.

-

Medical Scrubs

×A surgical scrub suit, durable hospital clothing that absorbs liquid and is easily cleaned, is worn as a baselayer underneath the overalls. It is normally tucked into rubber boots to ensure no skin is exposed.

-

Overalls

×The overalls are placed on top of the scrubs. These suits are similar to hazardous material (hazmat) suits worn in toxic environments. The team member supervising the process should check that the equipment is not damaged.

-

Double gloves

×A minimum two sets of gloves are required, covering the suit cuff. When putting on the gloves, care must be taken to ensure that no skin is exposed and that they are worn in such a way that any fluid on the sleeve will run off the suit and glove. Medical workers must change gloves between patients, performing thorough hand hygiene before donning a new pair. Heavy duty gloves are used whenever workers need to handle infectious waste.

-

Apron

×A waterproof apron is placed on top of the overalls as a final layer of protective clothing.

-

Boots

×Ebola health workers typically wear rubber boots, with the scrubs tucked into the footwear. If boots are unavailable, workers must wear closed, puncture and fluid-resistant shoes.

COVER YOUR EYES

If an infected droplet does get on to your skin, it can be washed away immediately with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitiser.

The eyes are a different matter. A spray of droplets from a sneeze directly into the eye, for example, could let the virus in.

Similarly, the mucous membranes of the mouth and inside of the nose are vulnerable areas, as is broken skin.

LAUNDRY

One of the most shocking symptoms of Ebola is bleeding. Patients can bleed from the eyes, ears, nose, mouth and rectum. Diarrhoea and vomit may also be tainted with blood.

A big infection risk is cleaning up. Any laundry or other clinical waste should be incinerated. Any medical equipment that needs to be kept should be decontaminated.

Without adequate sterilisation, virus transmission can continue and amplify.

Minute droplets on a surface that hasn't been adequately cleaned could, in theory, pose a risk. And it's unclear how long the virus could sit there and remain a threat. Flu viruses and other germs can live two hours or longer on hard environmental surfaces like tables, doorknobs, and desks.

The nurse who recently became infected while caring for two Ebola patients in Spain had twice gone into the room where one of the the patients was being treated - to be directly involved in his care and to disinfect the room after his death. Both times she was wearing protective clothing.

Soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitisers readily disrupt the envelope of this single-stranded RNA virus, and decontamination with dilute bleach is effective and readily available even in remote settings.

CONDOMS

Generally, once someone recovers from Ebola and they have the all-clear, they can no longer spread the virus.

But according to the World Health Organization Ebola can be found in semen for seven weeks and some studies suggest it can be present for up to three months.

For this reason, doctors say that people who recover from Ebola should abstain from sex or use condoms for three months.

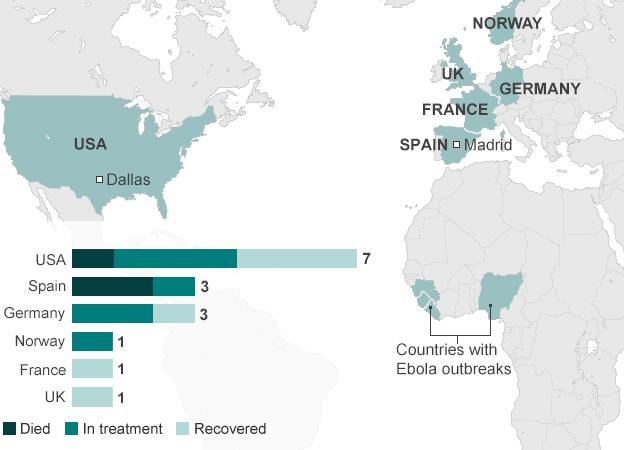

Ebola patients treated outside West Africa*

*In all cases but two, first in Madrid and later in Dallas, the patient was infected with Ebola while in West Africa.