Ebola treatments - how far off?

- Published

With the death toll rising and the disease still spreading, the race is on to find a treatment for Ebola.

Experts already know lots about the virus and how it attacks, but fighting it with a drug is newer territory.

Since Ebola was first identified, in 1976, every outbreak has been contained with strict hygiene - isolation of patients and suspected patients, ensuring staff wore suitable protective clothing and carried out proper cleaning and disposal of clinical waste.

There have been no drugs to do the job because developing them is extremely expensive, and, until now, the major pharmaceutical companies have not seen enough of a market. That's changing.

Known target

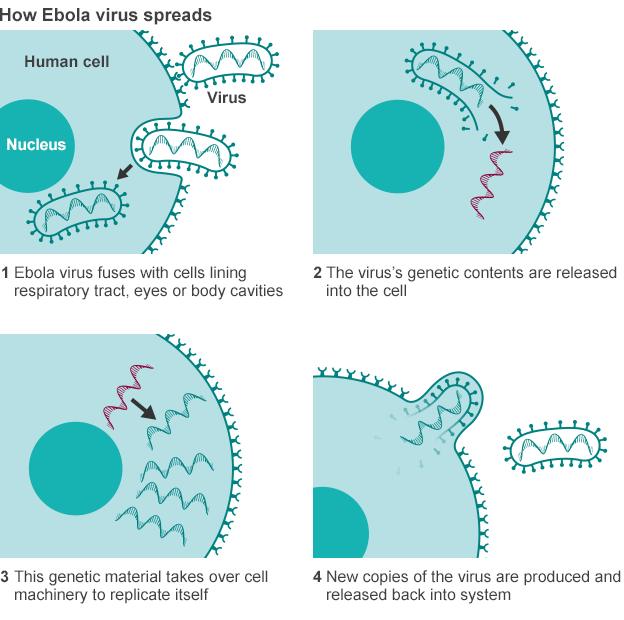

The virus can enter the body via infected droplets (blood, vomit, faeces) through broken skin or mucous membranes such as the eyes, the lining of the nose or the mouth.

Once inside, it rapidly multiplies in the blood, taking over and attacking cells.

The disease is not airborne like flu. Very close direct contact with an infected person is required for the virus to be passed to another person. Infection may also occur through direct contact with contaminated bedding, clothing and surfaces.

All of this has been known for nearly 40 years, but only now is the world really gearing up to the threat.

Medical weapons

Scientists are focusing their efforts on two approaches:

treatments to help people already infected with the virus

vaccines to protect people from catching it in the first place

There are lots of different experimental vaccines and drug treatments for Ebola under development, but they have not yet been fully tested for safety or effectiveness.

Experimental drugs such as ZMapp have already been given to patients in the current outbreak, but they have not saved all patients. Two US aid workers and a Briton recovered after taking it, but a Liberian doctor and a Spanish priest died.

The medicine has only previously been tested on animals, and experts say it is still unclear whether the drug boosts chances of recovery.

Stocks have been extremely limited, and the manufacturers of the drug say it will take months to increase production.

Donor blood

One of the first therapies to reach the frontline could be the blood of survivors.

They will have mounted an immune response capable of defeating the virus and antibodies that attack Ebola will still be loitering in their bloodstream.

Taking blood and emptying it of blood cells leaves behind an antibody-packed plasma which can be injected into patients.

In theory this should help the patient fight the virus. However, this has been tried only a handful of times before and it is unclear how effective it would be.

Also this is not some perfectly manufactured drug or vaccine. The effectiveness of the serum could vary from survivor to survivor.

Vaccines

The trial of the vaccine started in the US this month

The US, UK and Canada are testing different kinds of vaccine in controlled clinical trials.

The aim is to have 20,000 doses that could be used in West Africa by early next year.

Normally it would take years of human trials before a completely new vaccine was approved for use.

But such is the urgency of the Ebola outbreak that experimental vaccines are being fast-tracked at an astonishing rate.

Russia recently announced it is also developing three vaccines, with one being ready for clinical trials within three months.

David Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said: "There's been a lot of international attention to making sure that clinical trials of new vaccines and medicines are done.

"And my feeling is that if the resources continue those studies could possibly be begun and already provide some initial answers before Christmas."

It is hoped these vaccines will offer protection by delivering a harmless agent that will teach the body how to mount an immune response against Ebola.

If the person then came into contact with the real virus, their body should already know how to fight it.

Tests are ongoing, but there is no certainty how well they will work.

Dr Ben Neuman, an expert in virus and from the University of Reading, said: "Trials in monkeys have been promising. But they get a very different type of Ebola to humans.

"In a person it's a different kind of disease and we don't know for sure if the same treatments will work.

"Plus we need to scale up the doses. People are a big, walking test tube essentially."

Given the size of the outbreak, it's also unlikely that there will be enough vaccine or medicine to go round - at least initially.

Until these medicines to fight Ebola are ready, the focus has to be on disease control.

It was basic techniques that beat previous outbreaks. The hope is they will do the same now.