Virgin Galactic descent system activated early, investigators say

- Published

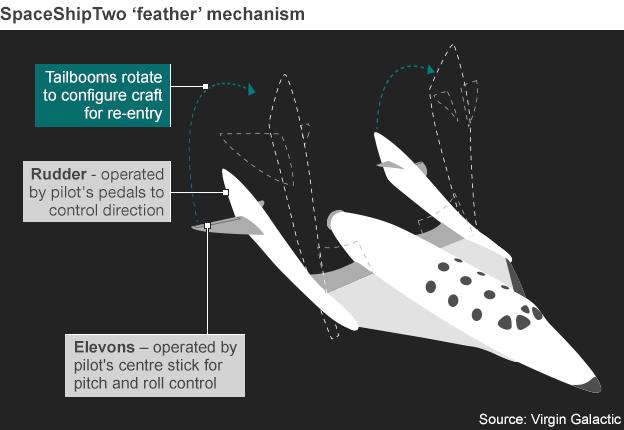

SpaceShipTwo with the tailbooms in the feathered position - from an earlier test outing

Investigators probing the crash of Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo craft have released the first hard facts about what happened during its ill-fated flight.

Onboard video and other data now indicate that a critical mechanism that ordinarily would only be used during the descent from sub-orbital space was activated at the beginning of the vehicle's journey skywards, on ascent.

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says SpaceShipTwo broke apart just two seconds after this "feathering" system was deployed.

Why the mechanism came out when it did, the inquiry team is not yet in a position to say.

But its untimely activation is now the focus of the investigation.

"This is not a statement of cause but rather a statement of fact. There is much more that we don't know, and our investigation is far from over," NTSB acting chairman Christopher Hart told a news conference in Mojave on Sunday.

Feathering is supposed to be one of the vehicle's key safety features.

The standard procedure is for the system to be deployed when the ship has reached its highest altitude, after it has broken through the atmosphere.

The twin tailbooms on the craft are rotated 65 degrees, from the horizontal to the vertical. The effect is to make the returning vehicle behave much like a shuttlecock.

As the air gets thicker on the descent and rushes over the booms, the drag on the plane means it naturally adopts a belly-down position ready for the glide back home - just as the feathers always ensure forward-facing flight for the conical projectile used in a game of badminton.

Feathering gets around the need for a complicated system of small thrusters that would otherwise be required to put the rocket ship into the correct re-entry attitude. Importantly, that belly-down configuration also slows the vehicle's fall.

The system worked to great effect on the prototype vehicle, SpaceShipOne, when it made its flights to suborbital space 10 years ago.

It goes without saying that feathering a vehicle while under rocket power and moving in excess of the speed of sound is a recipe for disaster. The aerodynamic profile is utterly changed along with the forces acting on the structure of the craft.

Video evidence

The pilots control the descent system by means of two levers - one to unlock the system; the second to deploy it.

Investigators could see from recovered cockpit video that co-pilot Michael Alsbury, who died in the accident, uses a handle to change the feathering system from the "lock to unlock" position as the vehicle passes Mach 1.0.

Mr Hart said that this action was taken earlier than would normally be expected (it should be executed at 1.4 times the speed of sound), but there is no evidence to suggest the pilots then moved the lever that actually engages the feathering system.

Tailboom structures were seen to rip off the vehicle (bottom-left)

"The lock-unlock lever was moved from lock to unlock, but the feathering lever was not moved. This was what we would call an uncommanded feather, which means the feather occurred without the lever being moved into the feather position," the investigator told reporters.

Engine recovery

The other key piece of information released by the NTSB concerned SpaceShipTwo's propulsion system.

Much of the discussion over the weekend has focussed on the rocket engine, on its new polyamide solid fuel and the suitability of its oxidiser, nitrous oxide.

Commentators have speculated whether some problem in the motor, perhaps an explosion, could have caused the accident.

But the NTSB's investigations directly contradict this idea.

"The fuel tanks were found intact with no indication of breach or burn-through, and so was the engine as well," Mr Hart said.

This was enough to prompt Virgin Galactic boss Sir Richard Branson to round on his critics.

He described the speculation concerning the motor's role in the accident as "garbage".

"I think that what you need to do is wait for the NTSB's final statement," he told the BBC.

"There will be a final statement and then we'll know exactly what happened; and the rumours and the innuendoes and the self-proclaimed experts I think will be put back in their box."

Sir Richard Branson told BBC News claims about the rocket exploding were "quite hurtful"