Suicide prevention is 'everybody's business'

- Published

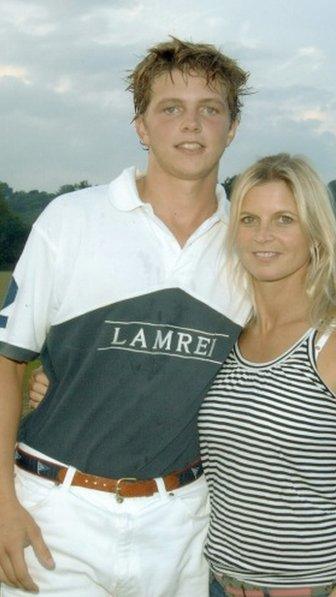

James Wentworth-Stanley, who took his own life at the age of 21, pictured with his mother Clare Milford Haven

The death of Charlotte Bevan and her newborn daughter in Bristol has prompted a review into the care she was given.

There are often questions about how such tragic situations might be avoided when family and friends become aware that a loved one is slipping into a decline.

To talk about this most sensitive of subjects, I met a polo player and former social editor at Tatler magazine, Clare Milford Haven, for a coffee in a quiet cafe at Brighton railway station.

Her eldest son, James Wentworth-Stanley, was sporty, bright and good-looking.

He took his own life at the age of just 21 in 2006.

He was in his second year of studying Spanish and business.

Described by his mother as "a doer", he also played in a rugby team and held down a hotel bar job.

James had returned to student life in Newcastle a few days after a minor operation had led to a change in mood.

'Horrendous and alarming'

Clare Milford Haven told me: "I wish I'd kept him under my watchful eye.

"I couldn't force his hand about returning to Newcastle - but I regret it, because then he took his own life.

"It was the most horrendous and alarming experience.

"There was absolutely no warning sign at all - we didn't see it coming. Our world was turned upside down.

"You have so many questions, and you just look for answers.

"A suicide bereavement is complicated by intense feelings of guilt and shame."

James Wentworth-Stanley sought help, in vain. He had been in contact with a GP, and a walk-in centre - which sent him to A&E two days before his suicide.

His mother has harnessed her pain to help others.

Clare Milford Haven helps to run the Alliance of Suicide Prevention Charities (TASC).

One of her goals is to set up a network of centres near hospitals.

Called James' Place, these would offer urgent face-to-face support for patients who are experiencing a crisis but are not in touch with mental health services.

Clare hopes the idea will be piloted in West London as well as in Brighton and Hove.

She said: "We'd like to have a hierarchy of staff - from volunteers to highly trained clinicians. But the atmosphere would be a non-clinical one.

"It's my dream that this would fill those very vital gaps in services."

We drive to a nearby library, where 11 people have gathered for a course called Safe Talk, or "Suicide Alertness For Everyone".

The audience - mostly community workers - watch and discuss video clips which demonstrate how to ask someone who is suffering a very simple but direct question: "Could you be thinking of suicide?"

The message behind the course is the importance of keeping someone who is vulnerable safe, and connecting them with services.

This might involve, for example, taking someone to a pharmacist or GP with any medicine they have stockpiled.

'People have doubts'

During a break, the instructor Chris Brown tells me how the charity she co-founded, Grassroots Suicide Prevention, is working to reduce what had been a very high suicide rate in Brighton.

She said: "We're trying to make Brighton a 'suicide-safe' town - it's all about education, awareness and training residents with brief courses like this one.

"Research tells us that people considering suicide have doubts about it. It shouldn't be regarded as an inevitable outcome.

"Part of a person considering ending their life wants to live, as well as the part of them that wants to die.

"But sometimes rules of confidentiality can mean that people don't get the help they might need from friends or family - this can result in a tragic outcome."

Advice to doctors from the Medical Defence Union says they should encourage patients to allow friends and family to get involved - and they can listen to the concerns of loved ones.

Technology could hold some promise here - Grassroots has launched an app called Stay Alive, which aims to point desperate people to help quickly.

But the Samaritans had to suspend their app called Radar, after criticism that its monitoring of tweets was intrusive and could encourage bullies.

This is an area in which any support has to be offered carefully and sensitively.

- Published7 November 2014