Is the obsession with NHS targets justified?

- Published

Targets have become synonymous with the NHS. From hospital operations to cancer care and fighting superbugs, successive governments have used them to keep a grip on performance.

And now - just five months away from an election - all eyes are on how the health service performs against its most high-profile measures.

But is this obsession with targets healthy and do they even work in the first place? The answer is not a simple one. One of the easiest ways to understand targets and the effect they have is to think of the health service as a balloon: squeeze one part and it bulges out elsewhere.

Take hospital waiting times, perhaps the flagship target of the whole NHS. When the target was first brought in in 2000 the bar was set at an 18-month maximum wait. Then over the course of four years it was brought down to six months.

However, it wasn't long before the balloon started bulging. The target at that time only measured the point from diagnosis to treatment starting so what happened was a bottleneck - some said "go-slow" - developed between GP referral and the patient getting the tests they needed for diagnosis. For some the waits for diagnosis were actually longer than the time spent officially waiting.

NHS pressures and targets

22 million

people visited A&E last year

3 million

are waiting for routine operations

-

4 hours max wait in A&E

-

18 weeks longest wait for routine ops

-

62 days max wait for cancer treatment

As criticisms grew, ministers in England - by this point health had started being devolved - responded with their most ambitious target yet. By 2008, they said, no-one should wait more than 18 weeks from GP referral to treatment. Some said it could not be achieved. But it was - and the other parts of the UK followed with their own versions of the target.

Problem solved? Not quite. The target gives hospitals some leeway to take into account exceptional circumstances - and so only 90% of patients have to be treated in 18 weeks. While it is a perfectly sensible measure, which is supported by doctors, it did have an unintended consequence.

When the 18-week deadline was missed in the early years, there was little incentive (in cold-hard performance terms at least) to treat that patient as the target only measured those that were treated within 18 weeks.

The result was that by the summer of 2011 the number of "long-waiters" was rising. There were over 100,000 people who had waited for more than six months and nearly 13,500 for over a year. Once again the balloon had bulged.

Since then there has been a big focus on tackling long waiters. But that has come at a cost. This summer - to keep the number of long waiters down - ministers announced there was to be a "managed breach" of the target to allow hospitals to keep up. The target has now been missed for the last five months.

Dr Mark Porter, a hospital doctor and leader of the British Medical Association, is scathing, saying they are "politically, not clinically driven".

"As pressure on services rises and care is increasingly rationed they can actually leave some patients waiting longer for treatment as, in order to meet one target, a backlog of patients with perhaps more serious illnesses is created."

A&E units

Such an effect is not unique to hospital operations either. It can be seen in A&E units too. Since 2004 hospitals have had to ensure patients spend no longer than four hours in emergency departments.

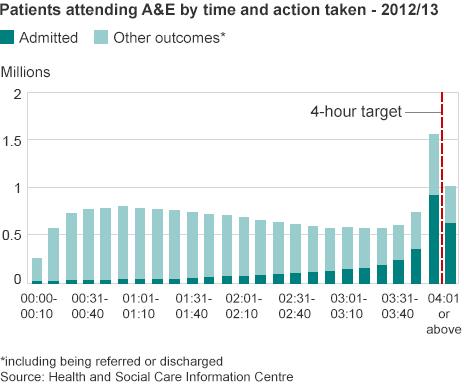

The NHS has largely succeeded over the years (although it is proving increasingly difficult in 2014). But if you look carefully at the data, you can see some strange patterns. Look at this graph below.

It shows how long patients waited in A&E during 2012-13, breaking them down into 10 minute groups. As you would expect there is a fairly uniform distribution in terms of when people are seen until, that is, the final 10 minutes before the four-hour mark. Then the numbers dealt with suddenly double.

Get involved on:

This is caused by a dramatic increase in admissions into hospital (signified by the dark green colour here) rather than being discharged or referred elsewhere. Once the four-hour mark passes, the numbers drop again.

So what is happening? An admission does not necessary mean a patient gets seen immediately. For some it simply means they are moved to another ward, often attached to A&E. These are sometimes called medical assessment units.

To most patients they will be undistinguishable from the A&E ward they had been in. Over the years there have been reports of patients facing long waits in these units, but because they have been admitted it is not counted in the official statistics. Once again the target has - to some extent - led to a bulge elsewhere.

Blunt tool

A bulge can also be seen outside A&E units when ambulances queue. Paramedics have to wait for a member of the A&E team to be ready before they can handover their patients. This should not take longer than 15 minutes, but a freedom of information request last year by the BBC showed it often does.

"The thing with targets is that they often displace the problem," says King's Fund director of policy Richard Murray. "They don't necessarily make things better overall, they just alter who loses out."

Nowhere is that clearer than with mental health. It has not been subject to a target and now there are regular reports of patient care suffering. The government's response? It's in the process of rolling out a series of mental health targets.

So does that mean they are entirely bad? No, of course not, says Mr Murray. "Waits are certainly shorter than they used to be, while their use in areas such as cancer or for infections like MRSA is perhaps more compelling. While some doctors may disagree, you have to wonder whether the results we have seen would have happened without them."

Nonetheless, they have always been - to borrow a quote from Tony Blair in 2005 - a blunt instrument. They give an indication of what is happening, but they don't always tell the full story.