Superbugs to kill 'more than cancer' by 2050

- Published

- comments

Drug resistant E.coli bacteria are already a significant problem in Europe

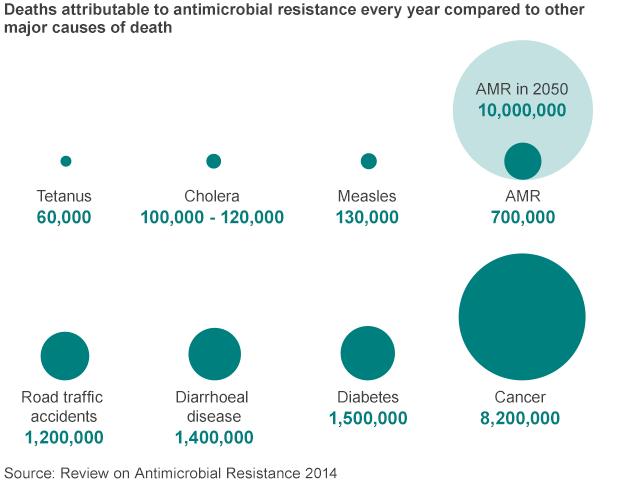

Drug resistant infections will kill an extra 10 million people a year worldwide - more than currently die from cancer - by 2050 unless action is taken, a study says.

They are currently implicated in 700,000 deaths each year.

The analysis, presented by the economist Jim O'Neill,, external said the costs would spiral to $100tn (£63tn).

He was appointed by Prime Minister David Cameron in July to head a review of antimicrobial resistance.

Mr O'Neill told the BBC: "To put that in context, the annual GDP [gross domestic product] of the UK is about $3tn, so this would be the equivalent of around 35 years without the UK contribution to the global economy."

The reduction in population and the impact on ill-health would reduce world economic output by between 2% and 3.5%.

The analysis was based on scenarios modelled by researchers Rand Europe and auditors KPMG.

They found that drug resistant E. coli, malaria and tuberculosis (TB) would have the biggest impact.

In Europe and the United States, antimicrobial resistance causes at least 50,000 deaths each year, they said. And left unchecked, deaths would rise more than 10-fold by 2050.

Mr O'Neill is best known for his economic analysis of developing nations and their growing importance in global trade.

He coined the acronyms Bric (Brazil, Russia, India and China) and more recently Mint (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey).

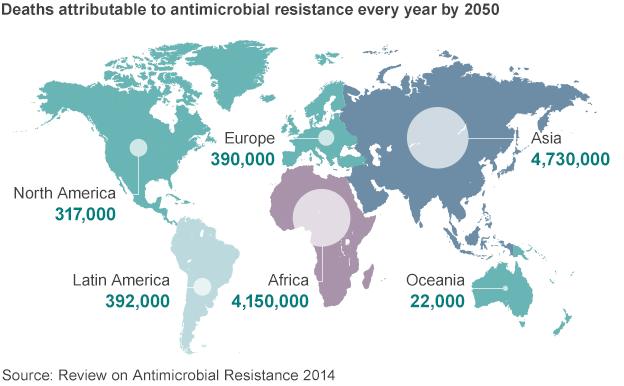

He said the impact of the would be mostly keenly felt in these countries.

"In Nigeria, by 2050, more than one in four deaths would be attributable to drug resistant infections, while India would see an additional two million lives lost every year."

The review team believes its analysis represents a significant underestimate of the potential impact of failing to tackle drug resistance, as it did not include the effects on healthcare of a world in which antibiotics no longer worked.

Joint replacements, Caesarean sections, chemotherapy and transplant surgery are among many treatments that depend on antibiotics being available to prevent infections.

The review team estimates that Caesarean sections currently contribute 2% to world GDP, joint replacements 0.65%, cancer drugs 0.75% and organ transplants 0.1%.

This is based on the number of lives saved, and ill-health prevented in people of working age.

Without effective antibiotics, these procedures would become much riskier and in many cases impossible.

The review team concludes that this would cost a further $100tn by 2050.

Mr O'Neill said his team would now be exploring what action could be taken to avert this looming crisis.

This would include looking at:

how drug use could be changed to reduce the rise of resistance

how to boost the development of new drugs

the need for coherent international action concerning drug use in humans and animals

Mr O'Neill said the support of the Bric and Mint nations was vital.

He noted that China would be hosting the G20 summit in 2016 and said he hoped this issue would be a focus of discussion.

'Compelling'

He said scientists seemed more certain that drug resistance would be a major problem in the short term, than they were over climate change.

Dr Jeremy Farrar, the director the Wellcome Trust, said: "By highlighting the vast financial and human costs that unchecked drug resistance will have, this important research underlines that this is not just a medical problem, but an economic and social one too."

Prof Dame Sally Davies, chief medical officer for England, said: "This is a compelling piece of work, which takes us a step forward in understanding the true gravity of the threat."

The review team concludes that solving the problem of drug resistance will be far cheaper than doing nothing and there was "cause for optimism" that the right steps could be taken.

This included university researchers and biotech entrepreneurs "teeming with ideas" including new drugs, vaccines and alternative therapies such as antibodies.

Investment

Laura Piddock, professor of microbiology at the University of Birmingham, is focusing her research on bacteria such as E. coli and salmonella, which are responsible for a growing level of drug resistant infections.

Both are so-called gram-negative bacteria, which have a complex cell wall that acts as a barrier to drugs. If they do penetrate the wall, they are "vacuumed out" by the cell.

She said: "My team is looking at what are the switches in those bacteria which turn that vacuum cleaner off, and at molecules which would have the same effect. If we can do that, we can make the bacteria sensitive to antibiotics."

Prof Piddock said there had not been enough global investment in finding new drugs.

She said: "It is very difficult to find drugs against bacteria like E.coli because they are so naturally resistant.

"We need more investment and new business models to ensure the pipeline is filled with promising molecules, to ensure that we can solve this problem, and make sure the drugs are there when patients need them."

- Published19 November 2015

- Published2 July 2014

- Published11 March 2013

- Published9 April 2011