Why not introduce more NHS charges?

- Published

In the early 1950s, the NHS was going through a tough period. Money was tight and demand was rising. So ministers came up with a radical plan - they introduced charges for dentistry, prescriptions and spectacles.

The move in 1952 was controversial, but did enough to get the NHS out of a tricky hole. With the finances tight again, should extending charges be under consideration now?

It is a question that has been asked several times in recent years. Research in 2013 by Reform, external, a centre-right think-tank, found a £10 charge for GP consultations could raise £1.2bn a year even with exemptions for age and income.

The issue was also discussed at British Medical Association and Royal College of Nursing conferences last year, although at both the motions drawn up calling on more charging to be introduced were not passed.

NHS charges: A short history

1948: Prescriptions, dental care and spectacles are all provided free on the NHS.

1952: Charging is introduced for all three. The prospect of this was a factor in the resignation of Nye Bevan from government a year earlier.

1965: Prescription charges are abolished by the Wilson government.

1968: Prescription charges are reintroduced. Treasury also supports GP consultation charges, but move blocked.

1988: Free NHS eye tests are abolished.

1999: Abolition of sight test charge for over-60s.

2004: Hospital charges introduced for telephones and television.

2006: Scotland introduces free eye tests.

2007-11: Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland abolish prescription charges.

When it comes to charging, there are several options that could be pursued. As Reform suggested, a charge for seeing a GP could be a valuable source of income.

There are an estimated 340m consultations annually, so the potential to raise money is obvious. But with the move towards email and telephone consultations and the increasing use of practice nurses to deliver them, a flat fee might not work.

Charges for visiting accident and emergency would generate less income unless they were set at a higher level, as there are just under 22m visits a year and introducing fees could prove problematic, given the busy nature of departments.

Another option that gets an airing from time to time is "hotel" charges for hospital stays. At any time there are about 120,000 beds occupied, so a £10 charge would raise £450m a year, and a £50 charge £2.25bn.

If that seems unfair, consider this: under the government's plan for a cap on care costs people in care homes will still have to pay about £33 a night in living costs.

'Founding principles'

What is more, charging is already commonplace in many health systems. An OECD analysis of 29 leading healthcare systems found 20 had charges for visiting a GP, while half had some kind of fee or co-payment for hospital treatment.

Like the NHS for eyes, dentistry and prescriptions, exemptions often exist for children, older people and the least well-off.

But despite all this, it is very unlikely that the issue of charging will be put forward by any of the main Westminster parties in the forthcoming election campaign. Why?

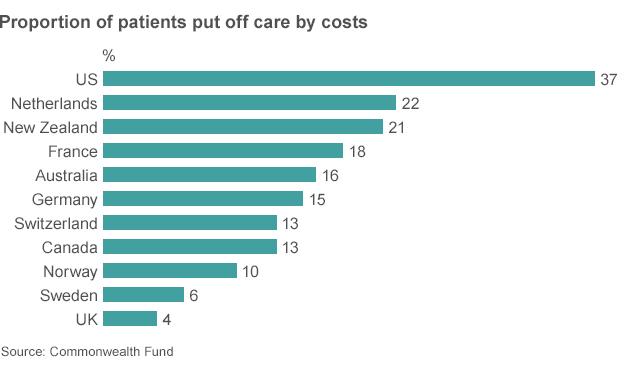

It comes down to access. Those involved with the NHS are proud that in the UK cost is not considered a barrier to seeking healthcare - as these figures from the Commonwealth Fund show.

Anita Charlesworth, chief economist of the Health Foundation, says that even though there are already charges in the NHS there is a fear that any extension of them would be seen as a "challenge to the founding principles of the NHS".

She adds: "The issue that people keep coming back to is whether this will have an impact on people accessing health services. If you deter people, it can just mean treatment is delayed and more expensive care is needed later on."

Does charging pay?

NHS dentistry cost £2.9bn in 2012-13, of which £650m was raised in charges.

Prescription charges raise only about £450m of the £9bn spent on prescription drugs.

Exemptions to prescription charges are so wide-ranging that only about 10% of items are paid for.

Scotland introduced free eye tests in 2006. Research suggests they are worth £440m a year in terms of improving quality of life and early detection - more than the cost of paying for them.

Perhaps the most thorough piece of research on this issue was done in the 1960s by RAND in the US. Overall it found there was little impact on health outcomes from the introduction of charges for most people.

But there was one exception: people on the lowest incomes, who are most likely to have the worst health in the first place.

This is why last year the Barker Commission, external, set up by the King's Fund to look at how the NHS and care system should be organised in the future, concluded introducing new charges "fail the criterion of equity" - and therefore there was "little scope for introducing them".

If anything, the review said it might make more sense to reduce charges to increase revenues. Confused? Among the problems with the current system are the anomalies that exist for fee exemptions.

For example, the over-60s get free prescriptions, but have to pay for dentistry. It is one of the reasons why less than 10% of prescriptions are paid for.

If this were scrapped, alongside the exemptions for pregnant women and some children, the prescription charge could be reduced from the current level of £8.05 per item to £2.50 and an extra £1bn would still be raised.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external.