Can 'supergeeks' save Kenya's babies?

- Published

Kenya has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world, but some university students are hoping their innovation can help reduce this

Broken machines litter the labour ward at Kenyatta hospital in Nairobi.

Nurses struggle to open oxygen valves with their fingernails because the buttons and valves are all broken on the baby incubator.

The hospital's last functioning examination light is slumped nearby.

This lack of basic equipment could explain why Kenya is struggling to reduce maternal mortality rates.

The UN estimates 7,000 Kenyan women die each year when giving birth, many due to bleeding.

Yet many of these deaths could be avoided by a simple measure - shining a bright light so the doctor can look for tiny tears in the uterus or cervix.

But in the country's hospitals many imported lamps are gathering dust because they are just too expensive to repair or replace.

Medical staff are forced to improvise by using their mobile phones as guiding lights.

Likewise, newborns perish because there are not enough incubators or other life-saving equipment.

Super-geeks

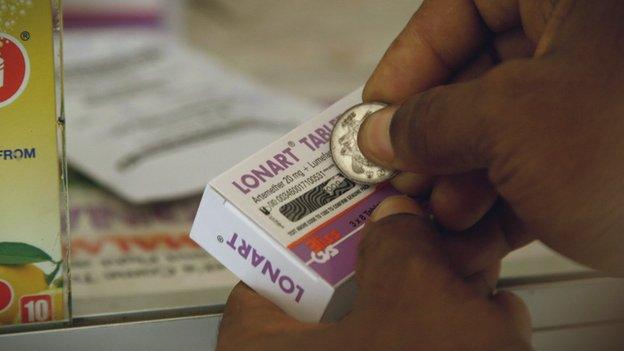

The struggle for life in the equipment-graveyard has inspired a lab of "super-geeks" to team up with the University of Nairobi healthcare workers to find innovative, high-quality and low-cost solutions.

Globally, a network of innovators are making low-cost designs in simple fabrication labs which have become known as FabLabs, external.

One FabLab team hard at work

Last year, the Irish charity Concern Worldwide started a pilot project for maternal, newborn and child health, which started bringing Kenyatta hospital staff and budding bioengineers together to design new machines.

They are already testing a new suction machine, and are working on prototype incubators, examination lights, and vacuum delivery and phototherapy machines.

The aim is to make machines for around £40 ($60), that run on LED lights and battery or solar power.

The hope is they will save lives for years to come.

Edwin Mbugua, the charity's innovations manager, said: "We believe that this project will catalyse a lot of local manufacture of medical devices and this will translate to increased availability of very high-quality, low-cost devices that will continue to improve children's lives.

"No mother or child should die during the process of birth."

'Like being in a war zone'

Dr Richard Ayah, who lectures in public health at the University of Nairobi, says such work is vital to cut the shockingly high maternal mortality rate.

"The highest is Mandera, at over 2,000 [deaths] per 100,000 births. Now at that level it means that women shouldn't even come to the health facility, it's that bad. It's like being in a war zone."

Some say a 2013 government policy to make maternity care free for all has only made things worse.

"There was no earlier preparatory work to make sure we had enough equipment, enough staffing, it was just a declaration," says Dr John Ong'ech, Kenyatta Hospital's head of reproductive health.

He added: "It has stretched whatever already existed."

The number of births at Kenyatta-East and Central Africa's largest referral hospital has increased from 10,000 to 15,000 per year and the number of premature babies treated there has doubled.

Around 2,000 babies, some weighing as little as 400g (under 1lb), are seen in the newborns' ward each month.

With so many babies, there are never enough machines to go round.

The hope is innovation will provide the solution.

- Published24 March 2015

- Published31 March 2015

- Published17 March 2015