Have we cured cancer?

- Published

Have we cured cancer?

If you walked past a newspaper stand, or flicked through a news app, this morning then you would have been left with that impression.

Well the short answer, if you're in a hurry, is no.

But something truly exciting is happening - the field of immunotherapy is coming of age.

It will not be a universal "cure" but immunotherapy is fast becoming a powerful new weapon alongside chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery.

Defender

Your immune system is your body's internal guardian and protector as it purges anything that is not "you".

It has a series of checks and brakes that prevent the immune system turning on healthy tissue (this is what goes wrong in autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis).

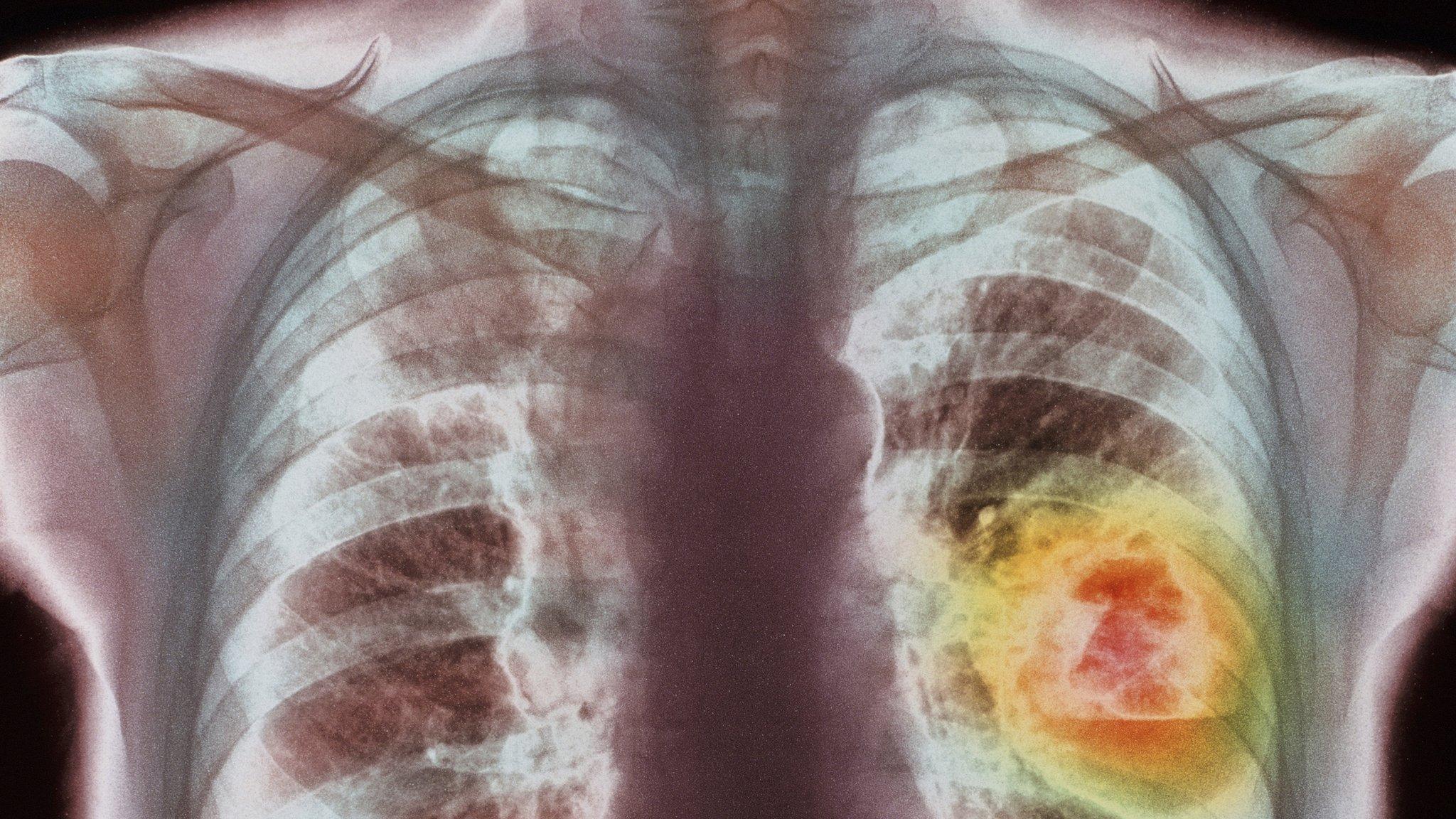

But cancer is a corrupted version of healthy tissue and can masquerade as normal to dodge our immune defences.

It performs the chemical equivalent of shouting "move along, nothing to see here".

And it does this by producing proteins on its surface that perform a chemical handshake with immune system cells to switch them off.

The immunotherapy drugs that have got people excited are like an oven-mitt that covers one of the hands, preventing the handshake.

The field has been developing for some time, but the explosion of front page newspaper headlines was triggered by data presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

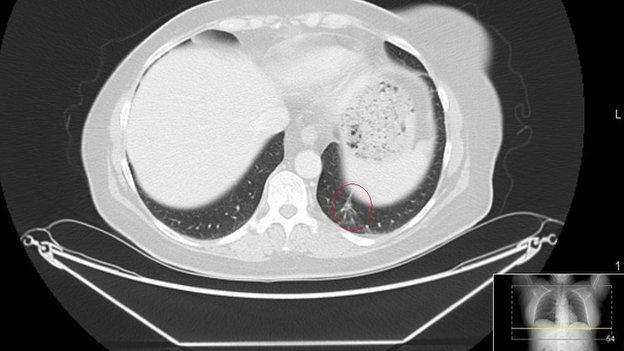

UK-led research showed that 60% of advanced melanoma skin cancers shrank when two immunotherapies were given in combination. The dual treatment stopped some of these deadliest cancers progressing for nearly a year.

Significant advance

The ASCO announcement came two days after another immunotherapy trial showed some lung cancer patients had their life expectancy doubled by immunotherapy drugs.

Smaller trials in a wide range of other cancers have also been presented - suggesting immunotherapy will have a role in many tumour-types.

Exciting? Certainly. A cure? No.

As Prof Karol Sikora, the dean of the University of Buckingham's medical school, told the BBC: "You would think cancer was being cured tomorrow.

"It's not the case, we've got a lot to learn."

So what are the words of caution?

For starters, these drugs do not work equally in everyone. Some people do spectacularly well, some do ok, and some do not respond at all.

The reason why is still unclear. Are cancers susceptible during just a short window in their development? Is it down to the type or quantity of proteins the tumours produce on their surface? We don't yet know.

Also, the therapies are likely to be very expensive, which means targeting the drugs on those who will respond will be key.

Long-term side effects are another a big uncertainty. Will the change to the immune system increase the risk of autoimmune diseases? So far the side effects seem to appear only during treatment, but long-term follow of patients who do respond has not taken place.

The research outside of melanoma and lung cancer is also still at a very early stage.

This is not a sudden breakthrough, or even the first set of really promising immunotherapy data.

The melanoma trial used a combination of two drugs - ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Ipilimumab is already recommended as the primary treatment for advanced melanoma in the UK.

So what we are seeing is a series of advances in a field that holds huge promise for the future. And that's exciting without throwing in the "cure" word.

- Published1 June 2015

- Published30 May 2015